In less than a generation, China’s roaring economy has created the world’s largest pool of eager spenders. The People’s Republic of China now has 116 million middle class and wealthy households, compared to just 2 million in 2000, according to McKinsey, a global consultancy. With a total population of 1.38 billion, many millions more should enter the consumer classes in the near future.

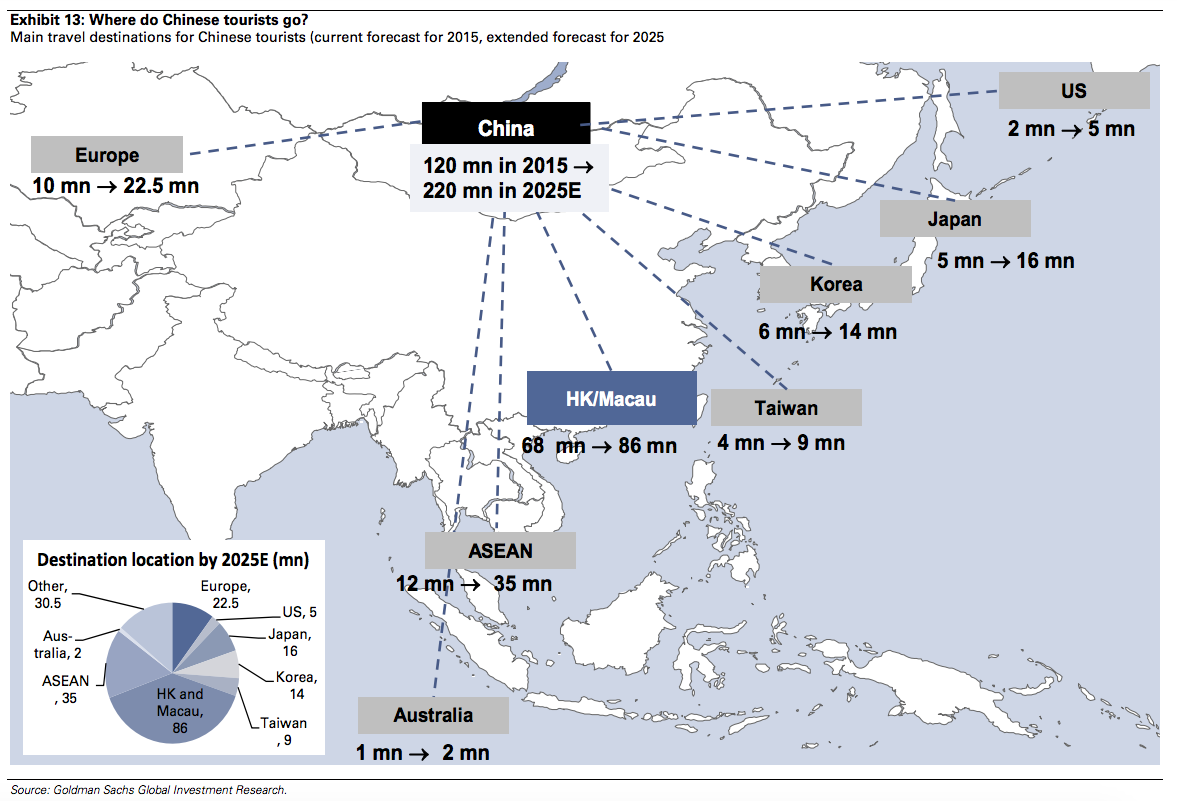

Boosted by these climbing incomes, and less government restrictions on travel, more Chinese are now traveling for fun — both domestically and abroad. In 2011, Chinese citizens took 70 million trips abroad for leisure and business. In 2014, according to the latest data available from the UN World Tourism Organization, that rose to 107 million. Goldman Sachs, a bank, predicts 100 million new Chinese will acquire passports by 2025. (Much of the data on tourism is collected by the private sector.)

Entertainment, including travel, will be the biggest growth category in China in the coming years, Goldman Sachs expects. According to UN data, Chinese travelers’ spending more than doubled between 2012 and 2015. Shopping plays a big role in where and how the Chinese vacation: A 2016 McKinsey survey found 47 percent say shopping is “an important part of my holidays.”

Chinese students abroad are also an economic phenomenon. Over 30 percent of the 1.04 million foreign college students in the United States hail from China, according to U.S. government-supported data. Their number has grown five-fold in 10 years, making Chinese students the largest foreign contingent by a wide margin. And sometimes their parents visit.

These social transformations and China’s economic heft are the focus of a growing body of academic inquiry.

For China’s neighbors, tourism – specifically Chinese visitors – is increasingly important to local economies, according to a 2016 paper by the International Monetary Fund. Indeed, much of the new research focusing on Chinese tourism is designed to help the industry understand how to best serve potential clients. But these same studies offer journalists context for reporting on the Chinese tourist’s economic impact or environmental footprint – at home and abroad.

Environmental anxieties

Traditionally, economic growth has had a negative impact on the environment – growth means construction, movement and other things that require the burning of fossil fuels. The domestic Chinese tourism industry’s emissions roughly doubled between 2002 and 2010, from 111.5 metric tons to 208.4 metric tons annually, according to a 2016 paper, but remained at about 2.5 percent of total emissions as overall output increased. Another study found tourism-related CO2 emissions inside China growing at almost 13 percent a year – largely from airplanes, buses and other forms of transportation – yet the industry overall is growing faster than the emissions.

The Chinese government actively encourages businesses to act sustainably, but offers “little guidance,” observes a 2016 paper. “The meaning of sustainability in the tourism sector is confusing and pro-business tourism development still plays a dominant role.”

Another 2016 paper looks at long-run and short-run correlations between tourism, economic growth and emissions.

The economics of tourism

As The Economist pointed out in 2014, the money Chinese citizens spend abroad influences China’s overall trade surplus. The value of Chinese exports is greater than its imports – that surplus is often a focus of concern in America’s Congress. But by this measure, Chinese tourist spending abroad is driving down the gap – with uncertain consequences for the global economy.

The spending, however, is slowed by onerous visa requirements on Chinese passport holders. They can visit 56 countries without applying for a visa. Compare that to Americans (155 countries) and Germans (158 countries), according to passportindex.org, a survey by the financial advisory firm Arton Capital. This is partly due to China’s own history of limiting visitors. A 2012 paper calculated that China lost $966 million in potential revenue due to restrictions ahead of the summer 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The tourism boom is motivating some Chinese firms to invest in foreign infrastructure to serve Chinese tourists. This forthcoming study looks at how those companies choose where and how to spend.

Back at home, China’s domestic tourism industry is associated with a reduction in income inequality, according to a 2016 paper in the Annals of Tourism Research. In part, that’s because some of China’s less-developed regions are becoming attractions for tourists from the wealthier (and more developed) east coast of the country.

Who are Chinese tourists and what do they want?

Many westerners can picture Chinese visitors touring en masse on giant buses. In 2011, a Chinese-speaking New Yorker staff writer accompanied a group on just such a tour of Europe. Though package tours may be cheaper, a 2016 study in the Journal of Travel Research found they offer Chinese tourists less overall satisfaction.

Other studies dispel notions of a homogeneous horde. In 2015, researchers in Ontario looked at Chinese communities in Canada, where Chinese-born residents (including from Hong Kong and Macau) make up the largest foreign-born contingent in the country (11 percent of the total). Whereas mainland China-born Canadians spend less on hotels when they vacation, they spend more than other Chinese Canadians on attending performances. Hong Kong-born Canadians like to spend money on hotels, fancy restaurants and spas. Canadian-born Chinese-Canadians, on the other hand, are not much different from other Canadians.

A 2016 paper looks at the diverse Chinese diaspora in North America and members’ distinct motivations for visiting their ancestral homeland.

These studies use demographic data to establish what different types of Chinese tourists look for in a holiday.

Coming to America

Chinese citizens are visiting the U.S. in record numbers. But what do they think of America? According to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, half of Chinese have a favorable opinion of the U.S., but 44 percent harbor negative views. Moreover, 45 percent say the U.S. is a “major threat” to China’s interests. (A 2015 Pew study found 54 percent of Americans had a negative view of China.)

When they arrive in the U.S., Chinese tourists can be reluctant to try new foods, observes a 2016 study in the Journal of Business Research, largely out of concerns over food hygiene. Moreover, confusion about American table etiquette is associated with a decline in Chinese tourists’ openness to unfamiliar foods, the study finds. They are less concerned about communicating with the wait staff in a restaurant, but place a premium on authentic culinary experiences. The study offers several recommendations: “Local restaurateurs need to ensure that they keep the authentic preparation of their food, because Chinese-style American food [burgers à la Beijing] might actually push Chinese customers away. Restaurants should also ensure the safety of the food. Providing a safe and hygienic environment is crucial. Further, restaurateurs should train their employees to be aware of the appropriate table manners in the Chinese culture and try to cater to them if at all possible.”

Chinese tourists who choose not to visit the U.S. describe disquiet about the distance, security or visa application process, according to a survey described in Tourism Management in 2013. Respondents also often “indicated that they had some negative impressions of the country, which also deterred them from visiting.”

Another group that has received American media attention is the so-called “birth tourists.” The New York Times reported in 2015 that federal authorities had raided several California businesses that may have helped thousands of Chinese mothers give birth on American soil. (Any child born in the U.S. is eligible for American citizenship, and this practice is not exclusive to nationals of any one country). A 2016 law review article looks at birth tourism specifically among Asians and how it is framed in popular culture.

How Chinese tourists get their information

As more Chinese tourists travel independent of tour groups, they look to Chinese-language internet resources for information. This 2016 paper, published in the Journal of Travel Research, looks at the motivations of independent Chinese bloggers who write about their trips. “Self-documentation and sharing” and the “hedonic enjoyment of blogging” are the strongest motivators, the authors found. They cite one typical blogger in his 30s who explained, “The original intention for blogging was not for fellow travelers’ reference. It was more for myself. When I recall this trip in the future, I would like to have some base. When I’m old, I will compile all my travel blogs into a book, and share it with my friends and posterity. They are my footprints in the world.”

Other resources:

- Demographic and economic statistics are available from the China Data Center at the University of Michigan, the World Bank and the official National Bureau of Statistics of China. (After years of complaints that official Chinese data are sometimes too good to be true, the head of the National Bureau of Statistics admitted some “fraud and deception” in how data were collected and presented. Earlier, this U.S. government paper found “serious deficiencies in the way the Chinese government gathers, measures, and presents its data.”)

- Union Pay, a popular Chinese credit card, is increasingly accepted abroad.

- A 2013 Congressional Research Service paper discusses concerns about Beijing manipulating its currency. By artificially decreasing the value of the yuan, as some American legislators have charged, China would make its goods more competitive in foreign markets.

- Megan Epler Wood, director of the International Sustainable Tourism Initiative at Harvard University, authored the 2017 book Sustainable Tourism on a Finite Planet. It explores how the explosive growth of tourism is impacting the natural world and makes recommendations for the decades ahead.

Keywords: Ecotourism, visitors, travel, food and leisure, sustainability, globalization