As the Federal Reserve bumped interest rates more than 4 percentage points in the lead-up to the Great Recession, investors steered toward increasingly risky bets on the U.S. housing market, according to a recent working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The Federal Reserve, or the Fed, is the central bank of the United States. The story goes like this: the Fed raised interest rates from 2003 to 2006. Banks in turn lowered their own interest rates on deposits. Some customers withdrew their deposits. Banks use deposits to back up and fund mortgage loans, so some mortgage lending decreased.

Higher interest rates meant fewer mortgages, exactly what rate increases had done in the past.

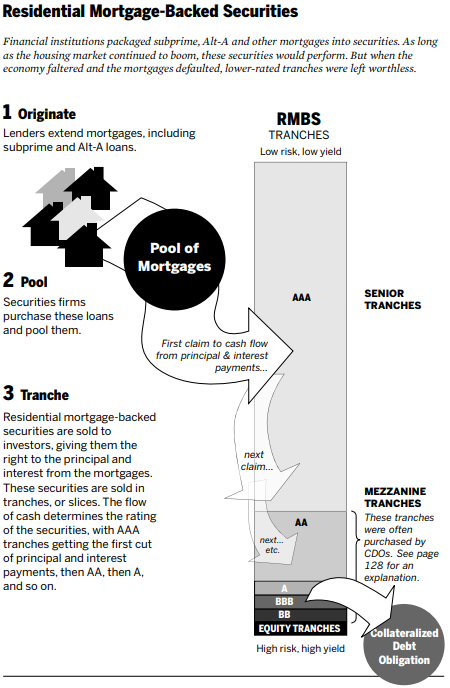

But from 2003 to 2006, financial institutions made up some unrealized loan profits through something called private-label securitization. The rise of the private-label securities market — which, in a nutshell, is made up of investors buying, slicing up and reselling bundles of mortgages — began in the early 2000s and followed the rise in interest rates.

When the private-label securitization market began to crumble, the Great Recession wasn’t far behind. The recession lasted from December 2007 to June 2009 and was the longest postwar recession in the U.S. (so far).

You may feel a small pinch while we get a little technical

When the Fed raises interest rates, the cost of borrowing money goes up for all sorts of things — home mortgages, cars, growing a business — anything a person or an entity could buy with a loan. In economic parlance this is called tightening. Interest rates go up, the cost of borrowing money goes up and the flow of loans usually slows down, like squeezing a garden hose.

“Which is not to say that the Fed shouldn’t have tightened,” says Itamar Drechsler, an associate professor of finance at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the authors of the paper. “We’re not making that statement. It’s just that tightening wasn’t effective in doing what it normally did.”

When Fed rates increase, banks often keep rates low on deposit accounts, according to the authors. Rates for run-of-the-mill checking and savings accounts are usually pretty low, but there are other kinds of deposit accounts that pay higher rates. What banks do is widen the difference between the interest they pay on deposits and the interest they bring in from loans, since they’re now making fewer loans. This difference is called the net interest spread, and it is the fundamental way banks make money.

Some customers respond to flatter returns by pulling their deposits. Banks need deposits. They are “by far the largest source of bank funding,” the authors write. The federal government guarantees some loans, like Federal Housing Administration loans, while banks also make long-term loans that are not backed by the government but are backed by and drawn from stable sources — like customer deposits.

During the run-up to the Great Recession, the loan-to-deposit ratio at large banks was 95 percent, meaning banks were lending nearly a dollar for every dollar they had in deposits. Though there were fewer mortgages being made, and some mortgages were being bundled and sold to investors, traditional banks also had increasingly less cash to cover defaults.

The ensuing economic crisis is history (though still being felt).

Something else was happening too: financial institutions that didn’t take deposits and weren’t federally insured were buying bundles of mortgages. This was the growing private-label securities market.

So, from 2003 to 2006 the Fed raised interest rates about 4.25 percentage points from just under 1% in late 2003 to 5.25% in late 2006. Banks bumped up their spreads, their stock of deposits dropped by 12.4% and they reduced their portfolio mortgage lending by more than a quarter, according to the new research.

A portfolio mortgage is a mortgage that a bank will keep on its books and won’t resell as a private-label security. Portfolio mortgage applicants often have to meet more stringent requirements than traditional loan applicants. The takeaway is that as the Fed raised rates, banks took on fewer loans they’d be on the hook for — and the market boomed for private-label securities.

“We basically are finding that as the Fed tightened, the mortgage market shifted from a much more stable source of funding through bank balance sheets — you need a stable source of funding where it is not going to dry up in times of stress — it shifted from that conventional market to where you are going to capital markets and you are exposing the housing market,” says Alexi Savov, an associate professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business and another author of the paper. “This funding could dry up. It’s a much more runnable market compared to bank deposits, which are more structured.”

Here comes the risk

Lenders that aren’t traditional banks are often called shadow banks. Shadow banks, also called nonbanks, are financial institutions that are not subject to the same government regulation as commercial banks. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission spent a year figuring out what went wrong during the financial crisis, and its Great Recession postmortem goes into detail on how and why the shadow banking system evolved.

(Hint: there was money to be made.)

Heading into the 2000s, nonbanks helped push mortgage securitization and mortgage lending itself into increasingly unregulated, shadowy waters.

“Why did the market become amenable to nonbank providers of credit? That’s an open question,” Drechsler says.

Loans not backed by the federal government — and not subject to federal loan risk standards — were bundled and sold as smart risks to nonbanks like Merrill Lynch, Bear Stearns and others. Again, this was the burgeoning private-label securities market. Loan officers who sold these private-label securities didn’t much care if a particular mortgage bundle was financially sound.

“You had no incentive whatsoever to be concerned about the quality of the loan, whether it was suitable for the borrower or whether the loan performed,” one loan officer trainer recounted in the FCIC report, released in 2011. “In fact, you were in a way encouraged not to worry about those macro issues.”

Credit rating agencies blessed many of these securities with their highest ratings. Nonbanks sliced up the loan bundles and sold the pieces, including riskier pieces, to other investors. Government-sponsored entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bought them too, and were bailed out. Some investors bought credit default swaps, which were insurance in case borrowers defaulted on their mortgages. And they did default, because more mortgages were going to riskier applicants.

In short, things got complex. Hundreds of investors might have owned financial products spun off from a single loan. “Like trying to untangle a vat of cooked spaghetti,” is how former New York Fed president Gerald Corrigan described these mortgage products to former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner.

The authors estimate that because of Fed tightening, private-label securities made up 10.2 percentage points more of all non-government backed mortgage lending from 2003 to 2006. This accounts for most of the 11.4 percentage point increase in the share of private-label securities, according to the authors.

“Our estimates suggest if the Fed hadn’t tightened, the shift to private-label securities would have been smaller,” Savov says.

Whether the Fed could or should have done anything differently remains unsettled. On one side, Stanford economist John Taylor has argued the Fed should have increased rates sooner to cool the housing market.

On the other, former Fed chair Ben Bernanke blames lax lending standards, not Fed monetary policy.

“Imagine you’re the Fed and it’s 2003,” Savov says. “They’re seeing the housing sector booming and are worried there is some overheating. You have data on how things used to work and you know from past cycles if you raise interest rates, mortgage lending would come down and that would slow down the boom. What’s happening is you are in a different environment. As you tighten, you have the same impact on banks as you always had, but now there is all this other type of mortgage lending that wasn’t there before.”

Americans may feel the fallout for decades, but unequally

Mortgage securities based on risky mortgages were a major reason the Great Recession was so bad for so many people. While the housing crisis hit family wealth across the board, subprime loans were more likely than prime loans to go under. Black applicants who were approved for loans were 2.6 times more likely to be offered a subprime loan compared with white applicants, according to a 2012 study examining more than 3.8 million loan applications.

The fallout from the crisis will probably cross decades. White wealth could be 31% lower by 2031 due to the Great Recession, while black wealth could decrease nearly 40%, according to a 2015 independent report commissioned by the American Civil Liberties Union, an advocacy organization.

Mortgage securitization is making a modest comeback

As in all horror stories, the monster is back — a little. Though the Fed seems poised to hold steady on rate increases for now (unless the president gets his way), recent rate increases have been concurrent with a small uptick in private-label securities, the authors find.

Time will tell if the story ends the same way as it did in the late-2000s. The Dodd-Frank Act included some requirements that are supposed to keep asset-backed securities from imploding again. Attempts to roll back core Dodd-Frank requirements have likely been overstated, according to Aaron Klein at Brookings.

“There is a ‘skin-in-the-game’ requirement where originators are required to hold part of the security,” Drechsler says. “My guess is the experience after the crisis was educational and probably scared away a lot of players in that game that are not going to come back fast. That may have made a bigger difference than anything else in limiting people’s enthusiasm, but there have been additional constraints.”

Research methods and conclusions

The authors used home purchase loan data from 2002 to 2006 provided through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. They drew their conclusions on bank deposit quantities from Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation data covering 58,604 bank branches around the country from June 2003 to June 2007.

Other data sources included SIFMA (a security industry trade association), U.S. Call Reports, Ratewatch and the U.S. Census. The authors’ findings include the following:

- From 2003 to 2006, the private-label securities market rose along with interest rates.

- Banks responded to rising rates by increasing deposit spreads, leading to a 12.4% drop in deposits.

- Banks also reduced their portfolio mortgage lending by 25.9%. But with more mortgages going to the securities market, total lending contracted only 4.4%.

- Private-label securities as a share of all mortgages not backed by the federal government grew 10.2 percentage points, accounting for nearly all of the total 11.4 percentage point increase in the share of private-label securities.

- The private-label securities market is again expanding, albeit slowly, concurrent with rising Fed rates.

By using bank deposits, the authors analyze how the Fed hiking interest rates before the Great Recession affected activity at individual banks across the nation.

“A feature of the deposit channel is we can look at different parts of the country,” Savov says. “That allows us to control for the aggregate business cycle, and that’s why the [Taylor-Bernanke] debate has been so hard to resolve. People have looked at the aggregate data. But I think on the deposit channel, you can shed more light.”

Angles for journalists

- Keep an eye on the private-label securitization market. SIFMA offers data to track and explore.

“I don’t see much coverage of that, and it is not as high as it was, but that seems like something worth paying attention to,” Savov says. “It coincides with this time when the Fed is raising rates. And you see bank deposit growth going down. It’s something to keep an eye on.”

- The Fed doesn’t make monetary policy by blueprint. There are numerous macroeconomic theories that compete with one other and may or may not influence Fed rate changes.

“There are [economic] theories but it’s not obvious that affects what policymakers do,” Drechsler says. “In some sense, it’s a journalistic argument. If the average person knew how much of an open question that is I think they would be quite surprised.”

Want to more insights on the U.S. economy? Check out our recent coverage on earnings inequality, reverberations from tariffs, and what happens to personal health when the economy suffers.