There’s a big problem in the multi-trillion-dollar bond market, according to a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper: A substantial portion of bond funds might be riskier bets than they seem.

The authors analyzed a sample of 1,294 bond funds from the first quarter of 2003 through the second quarter of 2019. They find that about 30% of those funds were misclassified, making them appear safer than they really were.

“This misreporting has been persistent, widespread, and appears strategic — casting misreporting funds in a significantly more positive position than is in actuality,” write authors Huaizhi Chen, Lauren Cohen and Umit Gurun. “Moreover, the misreporting has real impact on investor behavior and mutual fund success.”

To the authors, this is an untold story of misplaced trust at financial services megafirm Morningstar, the go-to third-party source for investors analyzing the performance and risk of bond funds and other securities. To Morningstar, these academics have taken an unwarranted “leap in logic” in claiming that bond funds are misrepresenting the creditworthiness of their holdings.

Morningstar writes in a blog post response to the working paper that “the authors assert funds misreport to us the credit quality of bonds their funds hold. We do not agree with this leap in logic.”

Later this month, the authors plan to submit their working paper to the Journal of Finance.

Update: Morningstar published a more extensive response and analysis on December 19, 2019.

Overlooking oversight?

Bonds are loans. Companies, governments and other entities use them to raise money. Bond funds are collections of bonds. Investors sometimes like them because they spread risk — if a particular bond doesn’t do well, it doesn’t matter much because other bonds in the fund can pick up the slack. The financial jargon boils down to an old adage: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

The fixed-income investment market in the U.S. is huge. Bonds of all types are, by and large, fixed-income investment instruments. That simply means investors receive interest payments on a fixed schedule. The U.S. fixed-income market represents nearly $43 trillion in outstanding debt, up from $19 trillion in 2002, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a securities industry trade group. The fixed-income funds in the authors’ sample had a market value of about $125 billion.

All loans — whether bonds, home mortgages or payday loans — come with some level of risk that the lender won’t be paid back. In the same way that banks use a credit score to evaluate whether to give someone a car loan, investors evaluate bond funds based on their level of credit risk.

Thing is, everyone has a different appetite for risk. One investor might like to go free climbing in her spare time and won’t mind a bond fund made up of a bunch of risky bonds. Another investor might plan her day down to the minute and will want a bond fund without any risky bonds.

For investors to make decisions that jibe with their risk tolerance, they need accurate information. This is where Morningstar comes in. Knowledge is the product they sell. Morningstar seeks to help investors make sense of the massive fixed-income market and decide where to park their money. For a company that pulled down $1 billion in revenue and $183 million in net income in 2018, the stakes of providing accurate information are existential.

“The reliability of our data and analytics is critical to our success, and we value transparency and collaboration to support investors,” Morningstar wrote in its response to the working paper.

The core problem, according to the authors, is that bond funds self-report credit risk summaries, and Morningstar takes those summaries at face value. Credit risk is hardly the only information that Morningstar offers, but it is among the most important that investors consider. Morningstar takes bond funds at their word — according to the authors — though the firm also acquires additional information from the Securities and Exchange Commission that could shed light on the creditworthiness of funds’ underlying holdings.

“Morningstar’s business model is dealing with collecting data and summarizing it for investors,” says Chen. “We believe there is really no oversight in this process.”

Anomalous observations

Chen and his co-authors noticed something unusual in their sample. Bonds that Morningstar reported as being good credit risks were offering high payouts. High-risk bonds usually compensate investors for taking a chance on them by offering high interest rates. More risk, more reward. But the authors found some low-risk funds yielding high rewards.

Another anomaly: A low-risk fund should be made up of mostly low-risk bonds, while a high-risk fund should have more high-risk bonds. But nearly a third of all funds the authors examined had a mixture of bonds that didn’t correspond to the creditworthiness Morningstar was reporting.

For example, a hypothetical fund in the authors’ sample might report that 90% of its bonds are low-risk and 10% of its bonds are high-risk.

“Now this would be no issue if funds were truthfully passing on a realistic view of the fund’s actual holdings to Morningstar,” the authors write. “Unfortunately, we show that this is not the case.”

Half of funds in the sample that achieved the highest possible credit rating should have been categorized as riskier, according to the paper. Funds may include hundreds or even thousands of bonds, so it would not necessarily be an easy task for Morningstar to check the math on every bond fund.

Still, 99% of these “misstatements,” as the authors call them, characterized funds as belonging to a safer category.

“For some funds, this discrepancy is egregious — with their reported holdings of safe bonds being 100% while their holdings are only a smaller fraction of their portfolios,” the authors write.

They also find that fund performance and misreporting could be linked. Misreporting happened more often after bond funds had a few straight quarters of poor returns. When performance improved, bond funds were likely to stop being misclassified.

Furthermore, the authors find that misclassified funds attract more investor dollars because they appear more attractive than their peer funds. It’s like this: Say two funds have the same risk profile, but one of them offers higher yields — most investors would probably be apt to “follow the money.”

Look before you leap

In Morningstar’s blog post response to the working paper, the firm acknowledges variations between the creditworthiness data that bond funds submit and the firm’s own data on those funds. Morningstar diverges from the authors on why those differences exist. The firm places blame not on fund managers misreporting credit risk — the “leap in logic” — but on holdings it classifies as “not rated.”

The firm gives the example that bond issuers are often credit rated, while their securities are not. Here’s one way to think about what this means: Say a city issues a bond for a new city hall. The city might have an investment-grade credit rating, but the specific bond it issues for the new city hall won’t be rated. A bond fund manager might rate this bond highly, because the city itself has a high credit rating. Morningstar, however, in its breakdown of the fund’s holdings, wouldn’t rate that specific bond.

“As a result, Morningstar’s calculated data generally shows higher levels of not-rated bonds than those self-reported by asset managers,” the firm writes in its blog post.

Morningstar’s proprietary methodology assigns these unrated holdings a low credit rating. These unrated holdings are mucking up the authors’ data, according to Morningstar, and it claims the authors’ findings disappear when controlling for holdings that are not rated.

The authors disagree. They released a response, writing that they went back and removed unrated holdings from their analysis and still found “a significant number of misclassified funds.”

The authors declined requests from Journalist’s Resource to make their underlying data immediately public, but they clearly lay out their methodology in their working paper — so their results should, in principle, be replicable for those with a paid subscription to Morningstar. The authors have shared with other academics the credit rating data they compiled. If the paper is published in the Journal of Finance, it would include a replication package with the underlying data and programming code.

“It’ll take a year,” Chen says. “We try to make what we do as transparent as possible.”

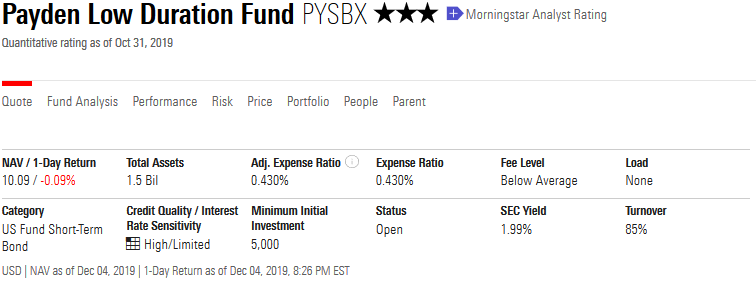

Morningstar’s second big issue with the working paper, according to the firm’s blog post, is that the authors conflate “categories” and “style boxes.” Morningstar categories are a sort of shorthand for some critical fund information: “The categories make it easier to build well-diversified portfolios, assess potential risk, and identify top-performing funds.” The style box refers to the area marked “Credit Quality / Interest Rate Sensitivity,” in this screenshot:

The category in the above example is “U.S. Fund Short-Term Bond.” By Morningstar’s definition, this category should be “attractive to fairly conservative investors, because they are less sensitive to interest rates than portfolios with longer durations.”

The point is that categories say something about a fund’s risk. But Morningstar in its response to the working paper makes clear that the style box — where it says “credit quality” above — doesn’t factor into category assignments.

“But if M* Styles are not as important as indicated in M* rebuttal, why are they displayed so prominently?” writes one commenter in a Morningstar chat forum, using “M*” as an abbreviation for Morningstar.

“I agree it can be confusing,” responds Jeffrey Ptak, head of global manager research for Morningstar. “Here’s how I think of style-box vs. M* category classification. The style-box is a snapshot at a given point in time. The category classification is a portrait — I suppose you could say a time-lapse — of what the fund’s style has looked like over a period of time, which we typically define as 36 months.”

The authors counter that “our findings still hold when we compare the funds against the Morningstar category.” What matters, they write, is their analysis relies on risk information on underlying bond holdings.

After the National Bureau of Economic Research released the working paper in November, the authors say they heard from at least one investment management firm corroborating their findings. That firm initially agreed to speak with JR, but later declined comment.