From the Scholars Strategy Network, written by Jan Leighley, American University, and Jonathan Nagler, New York University

Elections are crucial to representative democracy, but voter turnout in the United States is far from universal. About 60% of eligible U.S. voters have cast ballots in recent presidential elections. Turnout is lower in off-year congressional, senatorial and gubernatorial contests; in 2014, between 28% and 58% of voters turned out in various states. In primary elections and local or municipal contests, participation is often even lower.

Does slack U.S. voter turnout matter? As a practical matter, if voters and non-voters look very much alike, then low turnout is far less consequential for representative democracy than if voters comprise a non-representative subset of citizens. Our research breaks new ground by probing participation in presidential elections from 1972 to 2008, to see whether voters have been representative of all citizens — not only in terms of important social characteristics but also in terms of policy views. Overall, we find that voters are not representative. People with higher levels of education and income are far more likely to cast ballots; and voters hold more conservative views than non-voters about issues relevant to economic redistribution.

Who votes in U.S. presidential elections?

Overall U.S. voter turnout declined slightly in 1976 and 1980, but has otherwise been relatively steady, or even increasing, since the 1980s. Variations in turnout are striking — with steady gaps by income and education and shifts over the years in turnout by race, gender and age:

- With variations in specific elections, turnout for the highest education group is about 78%, compared to a turnout rate of about 60% to 65% for the middle education group and about 50% for those in the lowest education group.

- Similarly, about four of every five people in the highest education group typically turn out to vote, compared to just half of those in the lowest income group.

- African-American turnout has increased substantially since 1972, while Hispanic turnout has increased only slightly and non-Hispanic white turnout has declined slightly.

- Back in 1972, women were slightly less likely to vote than men, but since 1980 women have become equally or more likely to vote.

- In the biggest shift, turnout by older Americans has increased substantially since 1972.

Adding up the changes, women and older citizens are now over-represented among active American voters — just as people with more education and higher incomes have always been over-represented.

The impact of electoral rules

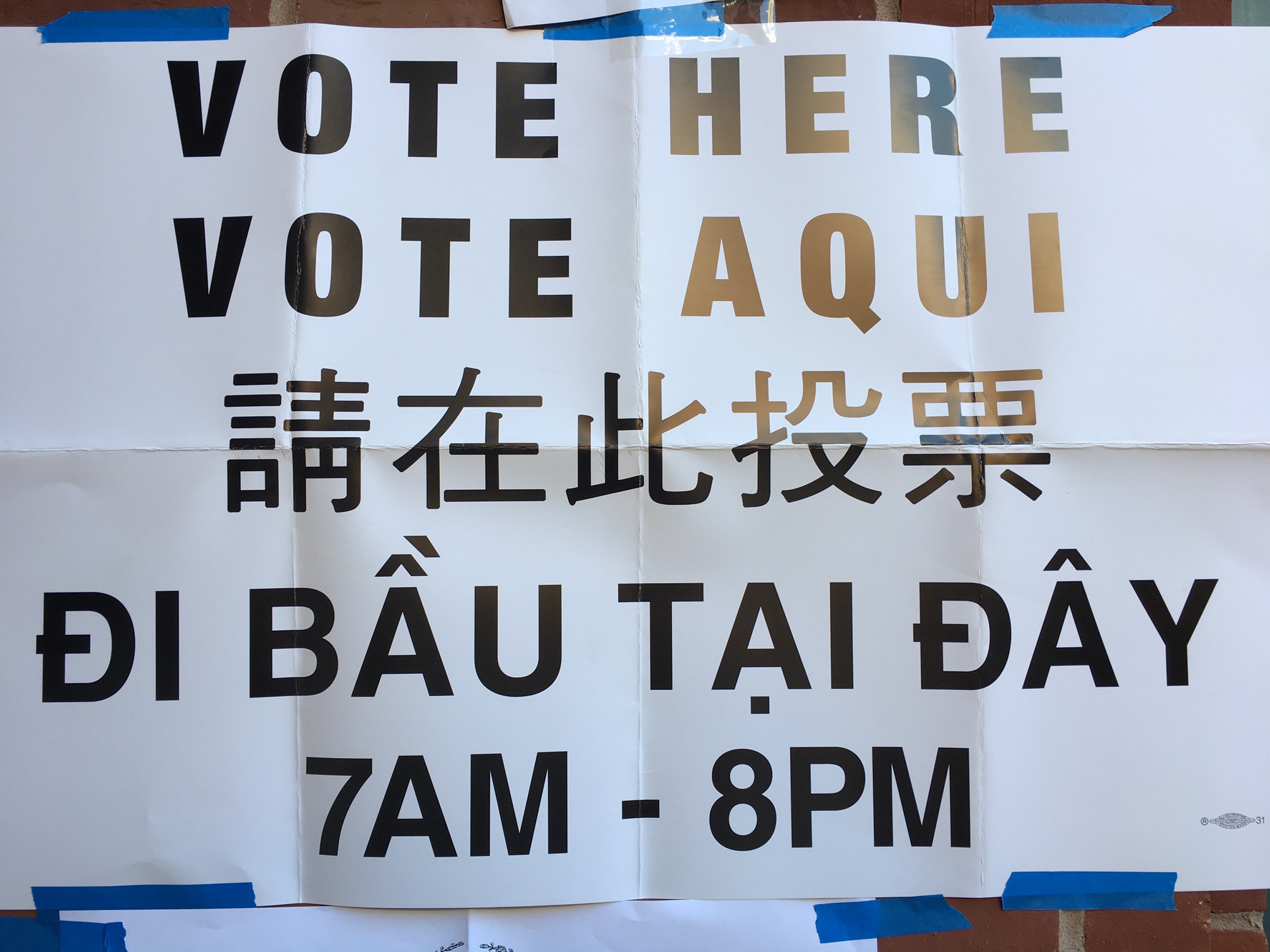

The time period of our study corresponds to a period in which many U.S. states adopted electoral reforms intended to ease voter turnout — such as absentee voting, Election Day registration and early voting periods. Do these reforms work? Most previous studies have focused on changes in one state or at one point in time, or have examined just one kind of reform. Our analysis provides the most comprehensive and accurate assessment to date of the causal effects of the length of voter registration periods, Election Day registration, absentee voting and early voting possibilities. Our findings show that reforms aiming to reduce the cost of voting can work, but much depends on the political context:

- States that instituted Election Day registration in the 1970s witnessed a 6-percentage- point increase in turnout.

- Absentee voting increases turnout, on average, by about 3 percentage points.

- Early voting can increase turnout about 3 percentage points, but gains in turnout depend on the length of the early voting period — and may well depend on other aspects of implementation beyond the scope of our analysis.

The importance of giving citizens a visible policy choice

People are more likely to vote when they think it matters. In our research, individuals who perceived a greater difference in the policy positions offered by presidential candidates between 1972 and 2008 were more likely to turn out to vote than people who did not see much difference. In short, the policy proposals offered by candidates in each election influence whether citizens vote at all, as well as whom they support. Turnout is higher in some presidential elections in part because candidates and parties espouse clearly different policies. Tellingly, moreover, poorer Americans have been less likely than others to perceive ideological differences between Republicans and Democrats. Here is a key reason poorer people vote less often: they are not aware of the different policies favored by candidates and parties.

Income inequality and voter turnout

Our research was partly motivated by a desire to better understand the consequences of rising economic inequality for U.S. elections. We were somewhat puzzled to learn that the relative turnout rate of wealthy versus poor potential voters has remained largely constant since 1972. In any event, over the past several decades America’s poorer citizens have clearly not been flocking to the polls to protest their decreasing share of the economic pie.

Future representativeness gaps in U.S. voter turnout are likely to depend on the political dynamics of elections — on the actions taken by candidates, parties and groups seeking to inform and mobilize potential voters and persuade citizens to cast ballots. Truly democratic elections require that all citizens understand the policy choices offered by candidates and why those choices matter. If America’s parties, candidates and activists work to clarify the stakes, we might begin to see both greater overall participation and more fully representative turnout in future U.S. elections.

Related research: Read more in Jan E. Leighley and Jonathan Nagler, Who Votes Now? Demographics, Issues, Inequality and Turnout in the United States, Princeton University Press, 2014.

The author is a member of the Scholars Strategy Network, where this post originally appeared.

Keywords: research brief, elections, early voting, voter turnout, presidency