Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle described unhygienic practices that were common across the U.S. meat industry. The public outcry following its publication spurred some of the nation’s first food safety legislation. More than a century later, the United States has made considerable progress on food safety, but foodborne illness remains a serious public health problem.

The Food Safety Modernization Act, signed into law in January 2011, is one of the most substantial regulatory updates in this area in decades. Four years later, it has yet to be implemented in a consequential way, although final rules are expected to go into effect later in 2015. The Act attempts to address the many historical problems and gaps with respect to industry practices, oversight and regulation. (Among other things, it required the creation of a recall search engine, which discloses the latest details about each incident.)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 48 million people in the United States become sick as a result of foodborne illness each year. Of those, 130,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die as a result of these illnesses.

The costs are also substantial for the food industry: A January 2015 paper from researchers at Utah State and Kansas State estimates that, after meat and poultry-producing food firms issue a recall, they lose on average $109 million in market equity over the next five days. The paper also notes that between 1994 and 2013 the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) “reported almost 1,300 meat and poultry recalls, representing approximately 638 million pounds of product,” with “nearly three-fourths of the recalls correspond[ing] to the most severe class of recalls.”

A 2014 report by the Congressional Research Service notes that, in addition to state and local governments, as many as 15 federal agencies are responsible for food safety regulation. The report states that the complex arrangement of federal agencies leads to overlapping and duplicate regulatory efforts. A 2010 report by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine recommended that policymakers create a single federal agency responsible for all food regulation in order to ensure a unified regulatory system.

Information on foodborne illnesses is maintained by a variety of regulatory sources. At the federal level, the CDC administers several foodborne illness surveillance systems that track national outbreaks. State and local departments of health also track cases of foodborne illness and may be responsible for food safety inspections of restaurants, schools, prisons and other facilities. There is hope that automation, computerization and the use of robots within processing plants may cut down on errors that can lead to tainted food and sickness, although such technology has not yet been scaled across the industry.

For quality research-based video and lectures on this topic, see this curated list. Below is some of the latest research on food safety in the United States; at bottom are two related graphics, from the CDC and the Congressional Research Service:

________

“Food Industry’s Current and Future Role in Preventing Microbial Foodborne Illness within the United States”

Doyle, Michael P. et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases, March 2015. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ253

Summary: “During the past century, the microbiological safety of the U.S. food supply has improved; however, many foodborne illnesses and outbreaks occur annually. Hence, opportunities for the food industry to improve the safety of both domestic and imported food exist through the adoption of risk-based preventive measures. Challenging food safety issues that are on the horizon include demographic changes to a population whose immune system is more susceptible to foodborne and opportunistic pathogens, climate changes that will shift where food is produced, and consumers’ preferences for raw and minimally processed foods. Increased environmental and product testing and anonymous data sharing by the food industry with the public health community would aid in identifying system weaknesses and enabling more targeted corrective and preventative actions. Clinicians will continue to play a major role in reducing foodborne illnesses by diagnosing and reporting cases and in helping to educate the consumer about food safety practices.”

“Local Health Department Food Safety and Sanitation Expenditures and Reductions in Enteric Disease, 2000–2010”

Betty Bekemeier, et al. American Journal of Public Health, Supplement 2, 2015, Vol. 105, No. S2.

Summary: “Objectives: In collaboration with Public Health Practice–Based Research Networks, we investigated relationships between local health department (LHD) food safety and sanitation expenditures and reported enteric disease rates. Methods: We combined annual infection rates for the common notifiable enteric diseases with uniquely detailed, LHD-level food safety and sanitation annual expenditure data obtained from Washington and New York state health departments. We used a multivariate panel time-series design to examine ecologic relationships between 2000–2010 local food safety and sanitation expenditures and enteric diseases. Our study population consisted of 72 LHDs (mostly serving county-level jurisdictions) in Washington and New York. Results: While controlling for other factors, we found significant associations between higher LHD food and sanitation spending and a lower incidence of salmonellosis in Washington and a lower incidence of cryptosporidiosis in New York. Conclusions: Local public health expenditures on food and sanitation services are important because of their association with certain health indicators. Our study supports the need for program-specific LHD service-related data to measure the cost, performance, and outcomes of prevention efforts to inform practice and policymaking.”

“Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food: Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2006–2013”

Crim, Stacy M. et al. 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 63, Issue 16.

Summary: Data from the CDC’s Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, which covers approximately 15% of the U.S. population, found no significant change in the incidence of foodborne illness over the period 2006 to 2013. During 2013, salmonella was responsible for more cases of illness, hospitalizations, and deaths compared to any other foodborne pathogen. Campylobacter, a class of bacteria found in raw poultry, raw milk, and fresh produce, was the second most common cause of foodborne illness. The study notes that the United States is failing to meet its goals for foodborne illness reduction as defined in the CDC’s Healthy People 2020 report.

“Attribution of Foodborne Illnesses, Hospitalizations and Deaths to Food Commodities by using Outbreak Data, United States, 1998–2008”

Painter, John A.; et al. 2013. Emerging Infectious Diseases. Vol 19 Issue 3.

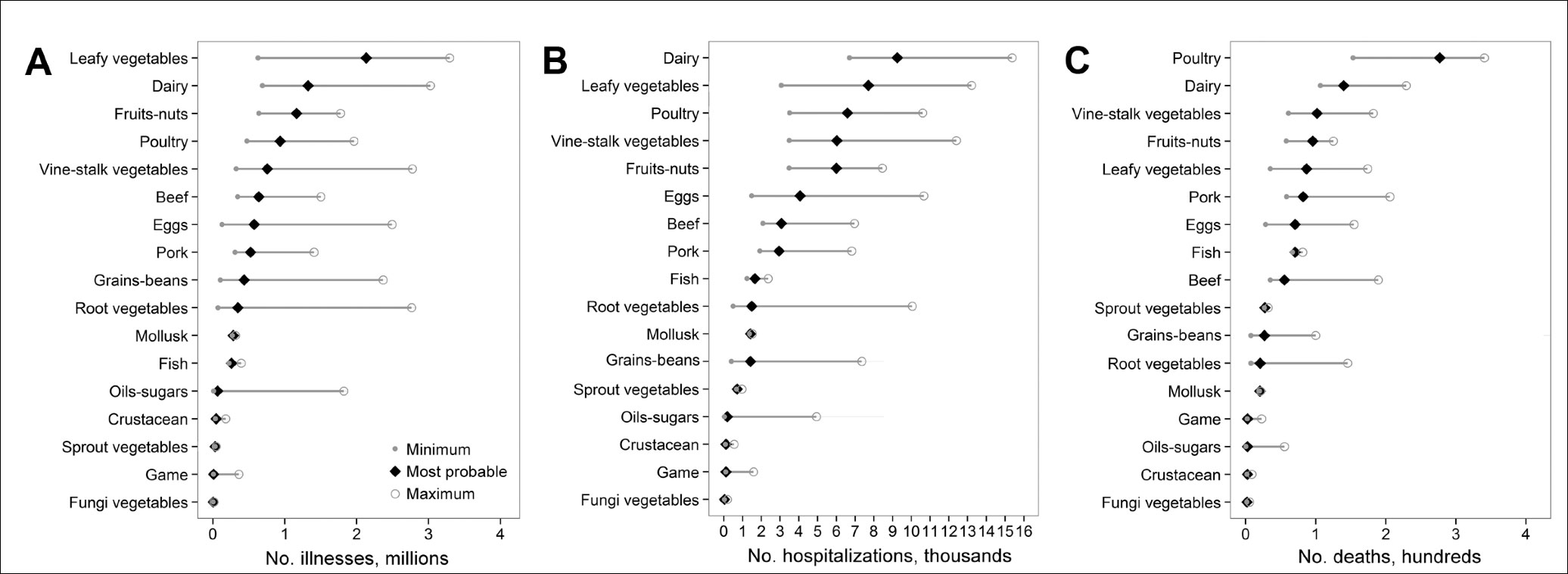

Abstract: “Each year, >9 million foodborne illnesses are estimated to be caused by major pathogens acquired in the United States. Preventing these illnesses is challenging because resources are limited and linking individual illnesses to a particular food is rarely possible except during an outbreak. We developed a method of attributing illnesses to food commodities that uses data from outbreaks associated with both simple and complex foods. Using data from outbreak-associated illnesses for 1998–2008, we estimated annual US foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths attributable to each of 17 food commodities. We attributed 46% of illnesses to produce and found that more deaths were attributed to poultry than to any other commodity. To the extent that these estimates reflect the commodities causing all foodborne illness, they indicate that efforts are particularly needed to prevent contamination of produce and poultry. Methods to incorporate data from other sources are needed to improve attribution estimates for some commodities and agents.”

“Economic Burden from Health Losses Due to Foodborne Illness in the United States”

Scharff, Robert L. Journal of Food Protection, 2012, Vol. 75 Issue 1.

Abstract: “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently revised their estimates for the annual number of foodborne illnesses; 48 million Americans suffer from domestically acquired foodborne illness associated with 31 identified pathogens and a broad category of unspecified agents. Consequently, economic studies based on the previous estimates are now obsolete. This study was conducted to provide improved and updated estimates of the cost of foodborne illness by adding a replication of the 2011 CDC model to existing cost-of-illness models. The basic cost-of-illness model includes economic estimates for medical costs, productivity losses, and illness-related mortality (based on hedonic value-of-statistical-life studies). The enhanced cost-of-illness model replaces the productivity loss estimates with a more inclusive pain, suffering, and functional disability measure based on monetized quality-adjusted life year estimates. Costs are estimated for each pathogen and a broader class of unknown pathogens. The addition of updated cost data and improvements to methodology enhanced the performance of each existing economic model. Uncertainty in these models was characterized using Monte Carlo simulations in @Risk version 5.5. With this model, the average cost per case of foodborne illness was $1,626 (90% credible interval [CI], $607 to $3,073) for the enhanced cost-of-illness model and $1,068 (90% CI, $683 to $1,646) for the basic model. The resulting aggregated annual cost of illness was $77.7 billion (90% CI, $28.6 to $144.6 billion) and $51.0 billion (90% CI, $31.2 to $76.1 billion) for the enhanced and basic models, respectively.”

“Using Online Reviews by Restaurant Patrons to Identify Unreported Cases of Foodborne Illness: New York City, 2012–2013”

Harrison, Cassandra; et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2014, Vol. 63, Issue 20.

Summary: “While investigating an outbreak of gastrointestinal disease associated with a restaurant, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) noted that patrons had reported illnesses on the business review website Yelp that had not been reported to DOHMH. To explore the potential of using Yelp to identify unreported outbreaks, DOHMH worked with Columbia University and Yelp on a pilot project to prospectively identify restaurant reviews on Yelp that referred to foodborne illness. During July 1, 2012–March 31, 2013, approximately 294,000 Yelp restaurant reviews were analyzed by a software program developed for the project. The program identified 893 reviews that required further evaluation by a foodborne disease epidemiologist. Of the 893 reviews, 499 (56%) described an event consistent with foodborne illness (e.g., patrons reported diarrhea or vomiting after their meal), and 468 of those described an illness within 4 weeks of the review or did not provide a period. Only 3% of the illnesses referred to in the 468 reviews had also been reported directly to DOHMH via telephone and online systems during the same period. Closer examination determined that 129 of the 468 reviews required further investigation, resulting in telephone interviews with 27 reviewers. From those 27 interviews, three previously unreported restaurant-related outbreaks linked to 16 illnesses met DOHMH outbreak investigation criteria; environmental investigation of the three restaurants identified multiple food-handling violations. The results suggest that online restaurant reviews might help to identify unreported outbreaks of foodborne illness and restaurants with deficiencies in food handling. However, investigating reports of illness in this manner might require considerable time and resources.”

“Relationship Between Food Safety and Critical Violations on Restaurant Inspections: An Empirical Investigation of Bacterial Pathogen Content”

Yeager, Valerie A.; et al. Journal of Environmental Health, 2013, Vol. 75, Issue 6.

Abstract: “While various safety control measures exist within the U.S. food system, foodborne illness remains a costly and persistent problem. The purpose of the study described here was to examine the relationship between violations of critical restaurant inspection items (“critical items”) and food safety as measured by the bacterial load of illness-causing pathogens. Specifically, the authors’ study looked at bacterial pathogens present in foods of two groups of restaurants, those that consistently scored poorly on critical items as compared to restaurants that performed superiorly in the same types of evaluation in Jefferson County, Alabama. Laboratory analyses indicated that 35.7% of the foods tested had detectable levels of Staphylococcus aureus, but no difference occurred between the two groups of restaurants. No other bacterial pathogens were found in any of the tested samples. A total of 45.2% of the food samples were received outside of recommended temperatures. Findings draw attention to the ongoing need to improve temperature control and hygienic practices, specifically handwashing practices, in restaurants.”

“Ciguatera and Scombroid Fish Poisoning in the United States”

Pennotti, Radha; et al. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2013, Vol. 10, Issue 12.

Abstract: “Annually, an average of 15 ciguatera and 28 scombroid fish–poisoning outbreaks, involving a total of 60 and 108 ill persons, respectively, were reported to FDOSS (2000–2007). NPDS reported an average of 173 exposure calls for ciguatoxin and 200 exposure calls for scombroid fish poisoning annually (2005–2009). After adjusting for undercounting, we estimated 15,910 (90% credible interval [CrI] 4140–37,408) ciguatera fish–poisoning illnesses annually, resulting in 343 (90% CrI 69–851) hospitalizations and three deaths (90% CrI 1–7). We estimated 35,142 (90% CrI: 10,496–78,128) scombroid fish–poisoning illnesses, resulting in 162 (90% CrI 0–558) hospitalizations and 0 deaths. Conclusions: Ciguatera and scombroid fish poisonings affect more Americans than reported in surveillance systems. Although additional data can improve these assessments, the estimated number of illnesses caused by seafood intoxication illuminates this public health problem. Efforts, including education, can reduce ciguatera and scombroid fish poisonings.”

_______

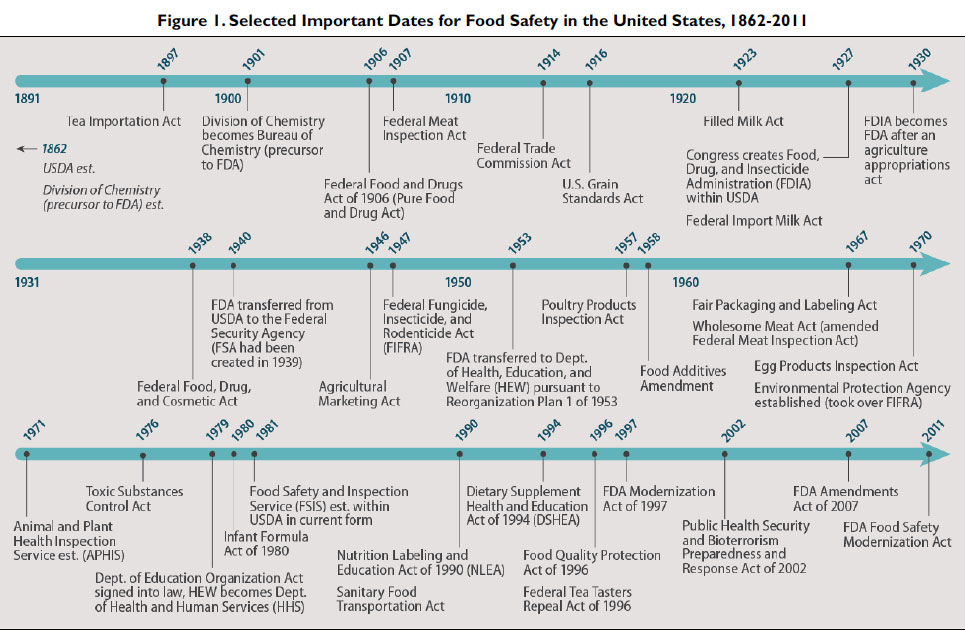

The following timeline is from a 2014 Congressional Research Service report, “The Federal Food Safety System: A Primer”:

And the following graphic published in the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases provides an estimate of deaths, hospitalizations and instances of foodborne illness attributable to various kinds of food:

Keywords: food, consumer affairs, safety, nutrition