A new childhood obesity prevention program helped kids get healthier, especially minority children, a study published in July 2018 in the American Journal of Public Health finds.

Previous research has shown that black children have a two-fold higher obesity prevalence than their white peers, and Hispanic children have a three-fold higher obesity prevalence. Obesity is tied to a number of chronic health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers.

The new study, led by researchers at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, followed 1,461 children, aged 2 to 4, from October 2010 until June 2015. All of the children in the study lived in Massachusetts and received assistance from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

WIC is a federal program that provides low-income families with healthy foods, nutrition education, health referrals and more. Participants typically visit WIC clinics three to four times a year, where families receive nutrition counseling and education and children have their height and weight measured. In addition, parents receive checks or vouchers to purchase approved foods each month.

Children in the intervention group went to WIC sites where providers were trained to counsel parents on childhood obesity prevention. These WIC providers also encouraged referrals to other obesity-related health programs. Children in the control group went to WIC sites where providers did not receive any special training.

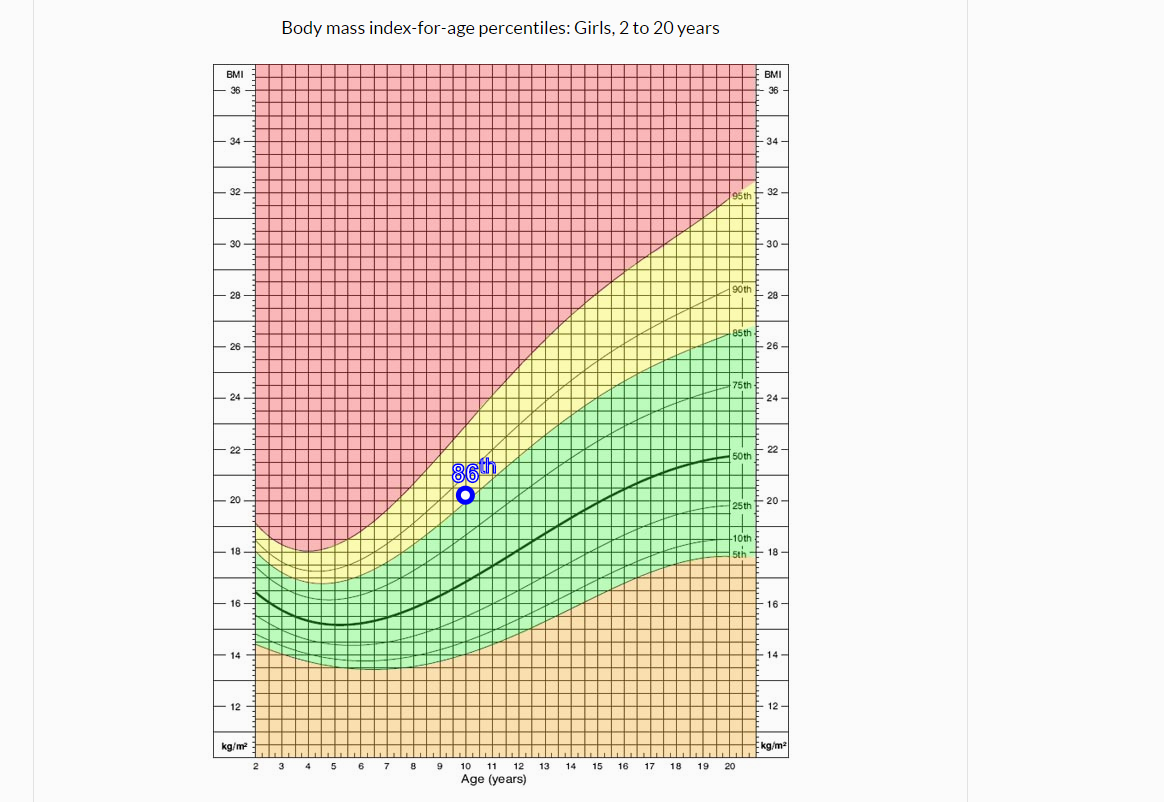

The researchers looked at whether the counseling program would lead to a reduction in body mass index (BMI) among children in the WIC program, and whether results would differ depending on a child’s race. BMI is calculated by dividing an individual’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. For children, BMI is then compared to the weight of peers of the same age and sex. Children whose BMI are above the 85th percentile for their age and sex are considered overweight; children whose BMI are above the 95th percentile are considered obese.

The program was broadly effective – both racial/ethnic minority children and white children experienced decreases in BMI. But the minority children experienced greater decreases.

Comparing the minority children in the intervention to their peers in the control group, while the intervention group experienced decreases in BMI, those in the control group saw increases. The researchers found that for each year racial/ethnic minority children (excluding Asian children) were involved in the study, their BMI decreased, on average, by 0.07. By contrast, minority children (again, excluding Asian children) in the control group saw a yearly 0.09 increase in BMI. Asian children were excluded from the analysis because the control group had a larger percentage of Asian children in it. “Because the control community had a higher percentage of Asian children with lower baseline BMIs, the study effect may have been weakened by confounding,” the authors write to explain why they subsequently removed this group from their analysis.

The authors suggest that the findings indicate how critical early intervention is in mitigating racial/ethnic health disparities. They write, “Our results suggest that without interventions to prevent childhood obesity when children are aged 2 to 4 years, racial/ethnic disparities in low- income children will grow, thus supporting the need to target early childhood to reduce childhood obesity and its racial/ethnic disparities.”

For more obesity research, including how the media covers obesity and trends in obesity-related deaths over 25 years, check out Journalist’s Resource’s coverage.