With confirmed cases of COVID-19 — the disease caused by a novel coronavirus — on the rise, organizations worldwide are encouraging or mandating that their employees telework.

Federal agencies in the U.S. are prepping plans for hundreds of thousands of employees to work from home, if needed. Big tech firms like Amazon, Google and Facebook are asking some employees to telework. Universities around the country have switched to online-only classes.

For many office workers, it’s not hard to do their jobs with a laptop at the kitchen table. But 34% of U.S. employees work in fields such as food preparation, retail sales, production, construction, maintenance and agriculture, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Global job and revenue losses underscore the ability of some industries over others to support work-from-home arrangements. Air travel, for example, relies on employees being there — think pilots, flight attendants and airplane mechanics.

Norwegian Air will cancel 3,000 flights — 15% of the airline’s flight volume — over the coming weeks, the company announced March 10. A leading business travel trade association estimates the industry could see worldwide revenue losses of $820 billion due to flagging international business travel. Travel agencies in Atlanta and Los Angeles have laid off staff, while some 145 drivers at the Port of Los Angeles have lost their jobs, according to The Washington Post. Cargo volume at the port fell 23% in February compared with last year.

So who gets to telework? People who work mostly online. And people with more education. Before the coronavirus outbreaks, 12% of high school graduates over age 25 without any college worked from home on a typical day, according to the 2018 release of a nationally representative survey the BLS has conducted continuously since 2003. Compare that with 37% with at least a bachelor’s degree, and 42% of workers with an advanced degree.

Then there is the fact that millions of mostly rural Americans don’t have reliable home internet access — occupations aside, working from home doesn’t work without decent internet.

More than 21 million Americans lack advanced broadband internet access, according to the latest report from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. “Moreover, the majority of those gaining access to such connections, approximately 4.3 million, are located in rural America,” according to the report.

The rural-urban broadband gap may be narrowing, but it remains stark. Roughly a quarter of rural Americans and a third of Americans in Tribal lands don’t have advanced broadband coverage — compared with less than 2% of people in urban areas, according to the report.

The FCC defines “advanced” broadband as offering download speeds of at least 25 megabits per second. Average download speed in the U.S. for fixed broadband is about 96 mbps, according to internet speed test firm Ookla, based on more than 115 million speed tests.

The ability to get broadband and having broadband are two different things. A Pew Research Center survey, released June 2019 based on a nationally representative sample of more than 1,500 adults, estimates that 73% of Americans have broadband at home — meaning more than a quarter of Americans don’t have home broadband. More than 90% of households making over $75,000 have broadband at home, compared with just 56% of households making less than $30,000 yearly, according to Pew. Median household income is $60,000 in urban areas and $44,000 in rural areas, according to Census data.

The five studies that follow offer more insight on who has the opportunity to telework, how telework can help prevent the spread of respiratory illness, key concepts related to digital inequality, and more.

Faruque Ahmed, Sara Kim, Mary Patricia Nowalk, Jennifer P. King, Jeffrey J. VanWormer, Manjusha Gaglani, Richard K. Zimmerman, Todd Bear, Michael L. Jackson, Lisa A. Jackson, Emily Martin, Caroline Cheng, Brendan Flannery, Jessie R. Chung and Amra Uzicanin. Emerging Infectious Diseases, January 2020.

The authors analyzed work attendance for 1,374 people aged 19 to 64 years who got the flu during the 2017-2018 flu season in six cities — Ann Arbor, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Seattle as well as Temple, Texas and Marshfield, Wisconsin.

People with the flu are most infectious during the first three days they’re sick, according to the authors. During those first three days, 28% of people in the authors’ sample who had a telework option didn’t work at all, compared with 41% of people without the option — indicating that people who worked remotely did so while sick.

Those without the option to telework were more likely to have taken time off, and those with paid leave — including sick leave and vacation time — were less likely to work during the first three days they were sick.

People who could telework and had paid leave more often were full-time, salaried workers, had higher levels of education and were “more likely to be encouraged by their employer to go home if they had influenza-like symptoms at work,” the authors write.

The gist: “We have documented that workplace cultures that encourage employees to refrain from coming to work when ill may play a crucial role in keeping workers away from the workplace when sick.”

Ellen Ernst Kossek and Brenda A. Lautsch. Academy of Management Annals, May 2017.

The authors examine 186 peer-reviewed articles on work-life flexibility around the world, including in telework policies. They note that in labor research “flexibility” means the ability to deviate from traditional 9-to-5 office work. Flexibility generally means that employees have some say over how, when and where they do their jobs.

“People may have limited choices and many constraints on the options available to manage their personal lives,” the authors write, adding that “organizations can benefit society and improve employee well-being by designing work to provide individuals within and across job groups some control over how work is enacted and reconciled with the rest of life.”

The gist: “Flexibility to control work location is rarely available for lower level jobs but benefits middle- and upper level employees, provided that individuals are able to control separation from work when desired and self-regulate complexity.”

Employment and Compliance with Pandemic Influenza Mitigation Recommendations

Kelly D. Blake, Robert J. Blendon and Kasisomayajula Viswanath. Emerging Infectious Diseases, February 2010.

The authors analyzed interviews they conducted by phone with a nationally representative sample of roughly 1,100 full- or part-time workers in September and October 2006, to gauge Americans’ ability and willingness to follow public health recommendations at home, school and work.

Roughly equal numbers of participants had only finished high school, had some college but no degree, or had a college or advanced degree. Two-thirds were white, 14% were Hispanic and 11% were black. Nearly a third had annual household incomes greater than $75,000. Three-quarters of people in the sample lived in an urban setting while about a quarter lived in a rural area.

Some 69% of respondents said they would not be able to work from home for a month if there were a serious outbreak of the flu, and 42% said they would not be paid if kept away from the workplace for that length of time. More than a quarter said someone in their household would lose a job or business if they had to stay home for seven to 10 days and avoid contact with the outside world.

“Job insecurity, whether real or perceived, is a real consideration for many working adults,” the authors write. “U.S. health authorities recommend that to prepare for a pandemic, businesses should establish policies for non-punitive liberal leave and flexible worksite accommodations.”

The gist: “We found that inability to work from home, lack of paid sick leave, and income are associated with working adults’ ability to comply and should be major targets for workplace interventions in the event of a serious outbreak.”

Acting and Reacting: Work/Life Accommodation and Blue-Collar Workers

Jaime E. Bochantin and Renee L. Cowan. International Journal of Business Communication, March 2014.

Participants in this research were skilled workers, like plumbers and electricians, and unskilled workers, like custodians, drawn from a large company in an unnamed state in the southern U.S. The authors interviewed a small sample of workers — 11 skilled and 15 unskilled — for anecdotes about how these workers navigate work-life balance.

Skilled and unskilled blue-collar workers used similar strategies to request schedule flexibility, such as going around supervisors to make requests higher up the chain of command, or pointing to past examples of hard work to persuade bosses to grant time off. What was different between skilled and unskilled workers was how supervisors responded.

“Unfortunately, many of the unskilled participants in our study indicated that they desired more flexibility and permeability, and this is reflected in the types of accommodations asked for,” the authors write. “For example, Sophia’s request to carry her cell phone on her at work to tend to her sick mother was denied by her supervisor, and Michele was not permitted to rearrange her schedule in order to take English courses at night to further her education.”

The gist: “In many of the examples shared by skilled blue-collar employees, their requests were almost always accommodated, which may suggest that those in skilled professions have an easier time getting requests granted,” the authors write.

Digital Inequalities and Why They Matter

Laura Robinson, Shelia R. Cotten, Hiroshi Ono, Anabel Quan-Haase, Gustavo Mesch, Wenhong Chen, Jeremy Schulz, Timothy M. Hale and Michael J. Stern. Information, Communication & Society, March 2015.

Digital inequality refers to gaps in access to and knowledge of computers, smartphones and the internet. The authors provide an overview of research on how digital inequality plays out across gender, age, race and ethnicity and income.

People with jobs, for example, are more likely to use computers, according to the authors. People who use the internet tend to earn more. By the time kids reach middle school, a digital inequality gap emerges between children familiar with the internet and computers, and those who aren’t. Digital skills matter, particularly as more jobs in sectors like manufacturing are automated, according to the authors.

“The shift toward ‘networked work’ — partly spurred on by technological transformations — has important consequences for organizational structure and job quality,” the authors write. “In the United States, national data show that telework and [information and communication technology] use are positively related to job autonomy and skill development.”

The gist: “Digital inequalities continue to combine with race, class, gender, and other offline axes of inequality. Even in countries with high levels of smartphone adoption, basic access to digital resources and the skills to use them effectively still elude many economically disadvantaged or traditionally underrepresented segments of the population.”

For more on the coronavirus pandemic, learn how oil prices have been affected, the research so far on how the virus is infecting the economy, plus 5 tips for journalists covering the outbreak.

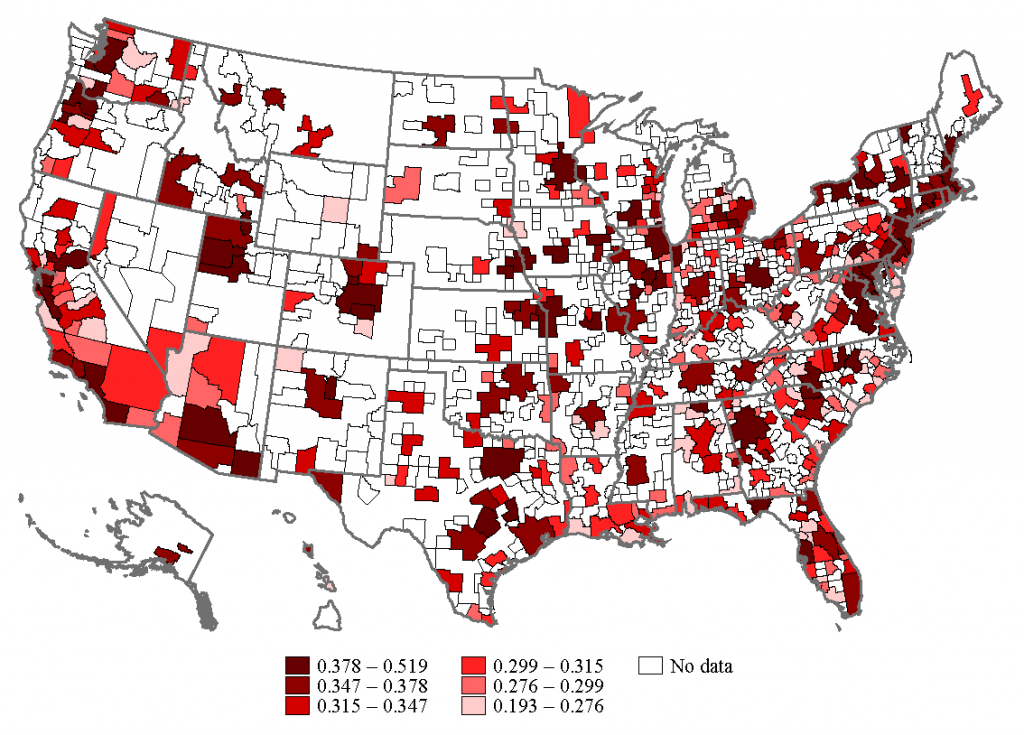

This article was updated on April 6 to add the metropolitan area level U.S. map of jobs conducive to telework, reproduced with author permission from the NBER working paper “How many jobs can be done at home?” The article was updated on April 7 to reflect a correction the authors made due to a coding error. The initial estimate of the share of jobs that can be done at home was 34%. The corrected share is 37%.