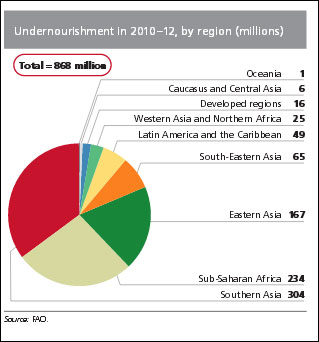

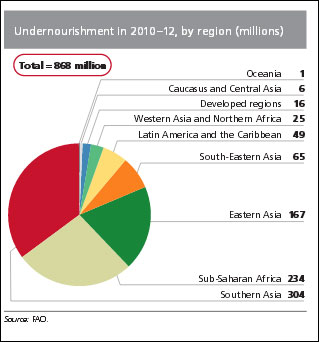

Even as new agricultural technologies develop, food insecurity remains a grave problem throughout many parts of the world. According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 12.5% of the global population is undernourished. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that even in the United States, 21% of households with children are food insecure. Food for 9 Billion, a joint news reporting initiative started in 2011 by the Center for Investigative Reporting, PBS, and Homelands Productions, highlights many of the myriad challenges that have resulted from rising international food prices and other barriers to food security.

Recent research on the 2011 uprisings in the Arab world has demonstrated a correlation between a rise in global food prices and social unrest. This echoes the findings of a 2011 World Food Programme paper, “Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict: Causes, Consequences, and Addressing the Challenges,” which notes that “food insecurity — especially when caused by a rise in food prices — is a threat and impact multiplier for violent conflict. It might not be a direct cause and rarely the only cause, but combined with other factors, for example in the political or economic spheres, it could be the factor that determines whether and when violent conflicts will erupt.”

Some evidence suggests that the relationship between violence and food insecurity is mutually reinforcing: In a 2012 study, “Conflict, Food Price Shocks, and Food Insecurity: The Experience of Afghan Households”, the researchers find evidence that households in provinces with higher levels of conflict suffer greater declines in food security than households in other provinces.

Some evidence suggests that the relationship between violence and food insecurity is mutually reinforcing: In a 2012 study, “Conflict, Food Price Shocks, and Food Insecurity: The Experience of Afghan Households”, the researchers find evidence that households in provinces with higher levels of conflict suffer greater declines in food security than households in other provinces.

But are rising global prices of all types of commodities always associated with conflict?

A recent study in the Review of Economic Studies, “Commodity Price Shocks and Civil Conflict: Evidence from Colombia,” finds that while price increases of certain goods can lead to increased conflict, price increases of others can reduce violence. The researchers analyzed information on the Colombian civil war from the Conflict Analysis Resource Center in Bogota as well as data on international commodity prices. The authors — Oeindrila Dube of NYU and Juan F. Vargas of Universidad del Rosario — conclude that “price shocks generate contradictory pressures on conflict. A price rise may generate greater rents to fight over via a rapacity effect. Alternatively, they may increase wages, raising the opportunity cost of fighting.”

The study’s findings include:

- Looking primarily at oil and coffee — Colombia’s two largest exports — the authors can determine that when the price of a labor-intensive agricultural commodity (coffee) rises, work hours and wages go up and conflict declines in the areas that produce the good.

- In contrast, when the price of less labor-intensive natural resources (oil) goes up, conflict also goes up in the areas that produce more of these resources.

- The 68% drop in coffee prices from 1997-2003 resulted in “18% more guerrilla attacks, 31% more paramilitary attacks, 22% more clashes, and 14% more casualties in the average coffee municipality, relative to non-coffee areas.”

- On the other hand, “a 137% increase in oil prices between 1998 and 2005 led paramilitary attacks to increase by an additional 14% in the average oil producing municipality.”

- These patterns held when the analysis was extended to six other major exports: “The positive relationship between natural resource price shocks and conflict holds for other commodities including coal and gold. In contrast, we find a negative correlation between agricultural price shocks and conflict in the case of sugar, banana, palm and tobacco.”

The authors note that several policy implications follow from these findings. They suggest that “price stabilization schemes which place a floor on the price of labor intensive commodities can help mitigate violence in the wake of price shocks.” They also suggest that governments should work to closely monitor funds generated by the country’s natural resources and, if necessary, reform fiscal structures in order to prevent these funds from fueling violent activity.

For additional reading on price shocks and violence in Colombia, see “Rural Windfall or a New Resource Curse? Coca, Income, and Civil Conflict in Colombia.”

Keywords: war, human rights, income shocks, conflict, commodity prices, natural resources