It’s no surprise that consumer spending in the U.S. fell off a cliff in March. That’s when bars, concert halls, movie theaters and other nonessential businesses across much of the country shuttered to try to stem the spread of the new coronavirus.

There’s a direct line between the ongoing lockdown and the coming decline in gross domestic product, one of the most closely watched indicators of the nation’s economic health among economic analysts and policy makers. That connection is due in large part to places that account for a large share of GDP, like Los Angeles and New York counties, having almost completely shut down.

There are lots of ways the federal government measures the health of the national economy: the unemployment rate, personal income, inflation — to name a few. Though no single measure can fully show how every corner of the U.S. economy is doing, gross domestic product paints the broad strokes, capturing the value of goods, services and public and private investments at a national level.

Economists expect grim returns when initial GDP numbers for 2020 are released later this month, chiefly because people are spending far less than they were a few weeks ago. Retail and food sales in the U.S. fell 8.7% in March from February to their lowest levels in 2.5 years, according to Census Bureau data from April 15. It’s the biggest one-month drop ever recorded in the U.S.

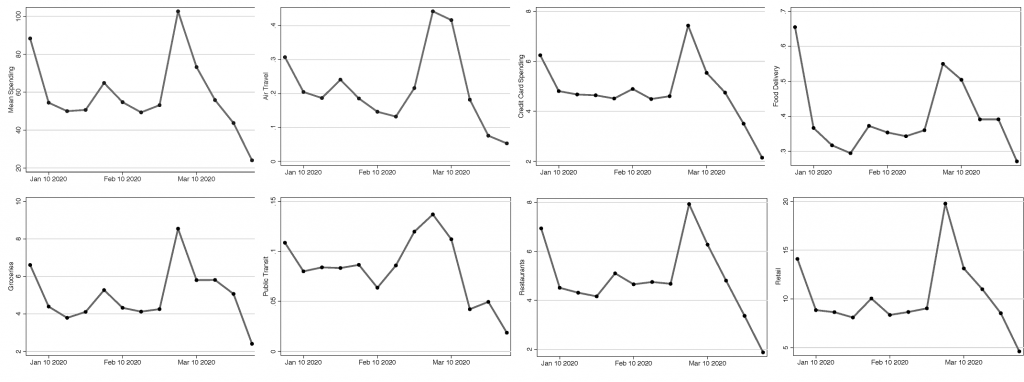

Research is now giving shape to this historic economic collapse. A new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research is the first to use recent data on household transactions, like going out to eat, to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic has curtailed purchases. The paper shows the sharp drop in consumer spending, which drives the U.S. economy, as the country shut down in March:

The authors analyzed spending data from 4,735 adults who signed up for SaverLife, a non-profit organization that aims to help people save money. People in the sample had to have made several transactions per month in 2020 worth a total of at least $1,000, recorded through their SaverLife accounts.

Note that the sample isn’t nationally representative — it doesn’t reflect the demographic makeup of the whole country — and participants skew toward people under 30.

“Older individuals with very high risk exposure may have behaved differently, and cut consumption more substantially,” the authors write.

The tradeoff for a less representative sample is timeliness. These are real transactions made just weeks ago.

From February 26 to March 10, people in the sample stocked up at grocery stores but were still going out to venues and restaurants. (Grocery sales, up 27% in March from February, were one bright spot from the April 15 Census data.) Public transit spending fell from March 11 to March 17, while spending on groceries and retail remained high during that period. On March 13, President Donald Trump declared a national emergency. From March 18 to March 27, spending dropped across the board.

“A lot of what the economy produces is goods and services for consumers,” says Scott Baker, an associate finance professor at Northwestern University and one of the paper’s authors. “So a large portion of the economy is people making restaurant meals and doing massages and producing toys and books and movies. This is all measured by the amount of money that people spend on consuming those goods and products and services.”

A quick primer on GDP

Real GDP grew 2.3% in 2019 to $19 trillion, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the federal agency that calculates GDP. “Real” means the BEA adjusts the numbers for inflation.

The agency uses a few data sources to measure GDP. It tallies private domestic investment, like construction spending and oil and gas exploration. It counts the value of exports, like food, automotive parts and other goods sent overseas, minus the value of goods produced abroad and sold here. Federal, state and local government investment are also part of GDP.

But the biggest chunk — about 70% of GDP — comes from money Americans spend domestically. Every dollar Americans spend at barbecue joints or barber shops or on transit passes or anything else is added to GDP. Consumer spending has accounted for about that share of GDP since the 1990s.

A magnitude 9 economic earthquake

The current situation more closely resembles a natural disaster than a traditional recession, according to economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The supply of things to spend money on has been stanched. It’s like a national-level Hurricane Katrina, the storm that devastated New Orleans in August 2005, write Jason Bram and Richard Deitz in an April 10 New York Fed blog post.

“Recessions typically develop gradually over time, reflecting underlying economic and financial conditions, whereas the current economic situation developed suddenly as a consequence of a fast-moving global pandemic,” Bram and Deitz explain.

Economists also like to analogize situations in which established systems are uprooted to “shocks.” The coronavirus pandemic has caused an economic shock — not unlike an earthquake. Didier Sornette, who heads the Financial Crisis Observatory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, was game when Journalist’s Resource asked him to rate the coronavirus recession and other major U.S. downturns on the Richter scale, which measures the severity of earthquakes.

The big one — the 1929 stock market crash and depression that followed — was a magnitude 10, according to Sornette. The 1987 stock market crash was a magnitude 7, and the 2008 housing bubble was a magnitude 8.5. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the decline in consumer spending that came with the Great Recession cost 3.2 million U.S. jobs. Sornette puts the coronavirus recession at a magnitude 9, with the caveat that “many unknowns remain.” Over the past month alone, more than 20 million people have filed new claims for unemployment benefits, according to the Department of Labor.

Shutting down the U.S. economy is an extreme step, but the stakes are life or death. As of April 17, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported more than 33,000 deaths in the U.S. and its territories from COVID-19, the disease the new coronavirus causes.

“In the near term, public health objectives necessitate people staying home from shopping and work, especially if they are sick or at risk,” former Federal Reserve chairs Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen wrote last month in the Financial Times. “So production and spending must inevitably decline for a time.”

Fatalities in the U.S. would almost certainly be higher absent widespread economic closure. In an NBER working paper from March — “The Macroeconomics of Epidemics” — researchers estimate half a million lives could be saved as a result of social distancing measures that drastically reduce consumer spending.

“Abandoning containment policies prematurely leads to an initial economic recovery,” write economists Martin Eichenbaum and Sergio Rebelo at Northwestern and Mathias Trabandt at the Free University of Berlin. “But it also leads to a large rise in infection rates. That rise causes a new, persistent recession.”

Dire forecasts

With businesses closed and the ranks of the unemployed growing, it follows that forecasts are dire for the advance GDP estimate scheduled for release on April 29. That estimate will cover the first three months of 2020. The St. Louis Federal Reserve estimated on April 17 that real GDP would plummet 15% in the first quarter.

Other estimates for the first quarter are not so gloomy. The Atlanta Federal Reserve on April 15 estimated a GDP decline of 0.3%, down from its estimate of 1% growth the week before. The St. Louis method differs from other federal GDP estimates in that it accounts for surprises — such as when macroeconomic measures, like initial unemployment claims, are much worse or better than forecasted.

Many economists think GDP will drop yet lower April to June, as job and spending losses rack up. GDP could shrink by 10% in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the first quarter, and the unemployment rate could reach 15% by midyear, according to a March 31 report from economists at Goldman Sachs.

The figure from the report that grabbed headlines was Goldman’s estimate that annualized GDP would fall 34% in the second quarter. Annualization is a common mathematical adjustment in economic analysis. Annualizing data shows what would happen if current trends continued over a year, allowing analysts to compare growth rates over different periods of time. St. Louis Fed researcher YiLi Chien recently calculated that the unemployment rate would be in the 26% to 51% range if Goldman’s GDP estimates are on target. Goldman expects a partial rebound in the last two quarters of the year.

“When people hear the economy is going to shrink by a third, they think that’s maybe a little bit implausible,” Goldman chief economist Jan Hatzius said in a podcast from early April. “But that’s not what we’re saying. We’re saying that the economy basically shrinks by 10% relative to the first quarter, or April shrinks by 13% relative to January.”

By the end of 2020, Goldman estimates GDP will contract about 6% compared with 2019. This is in line with estimates from the International Monetary Fund, the group of 189 countries that aims to increase global financial stability. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook report from early April projects that advanced economies, like the U.S., Canada, Japan and the United Kingdom, will contract on average about 6% in 2020 due to “the Great Lockdown,” as IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath dubs it.

Money in the bank

The U.S. is trying to buoy the economy with relief measures like the $2 trillion package Trump signed into law on March 27. In addition to hundreds of billions in loans to small and big businesses, the relief package includes unemployment benefits and cash payments to Americans. Unemployment benefits will extend through the end of the year, longer than the typical benefit period of about six months.

Extended benefits are good for recipients, according to a July 2019 paper in the American Economic Review from economists Peter Ganong and Pascal Noel at the University of Chicago. They analyzed spending data from 182,000 households in 20 states that received jobless benefits from January 2014 to June 2016.

A quarter of households were unemployed longer than six months, and exhausted their benefits. For those households, Ganong and Noel found that monthly spending fell 6% when benefits began, decreased less than 1% per month while households received benefits, then dropped another 12% after benefits ran out. Those households didn’t save while they were getting benefits, and after benefits ran out their spending fell by a larger share than in the benefit months combined. The upshot? “It’s much more important to give households money for a longer period of time than more money up front,” Noel says.

Households that exhausted benefits cut spending most at home improvement stores, by about 20%. Spending at discount stores fell about 19% and spending at department stores fell about 18%. Spending on dining out also fell, by about 16%. Medical co-payments fell about 14%, while spending for auto repairs declined about 13%. The trend is that when unemployment benefits run out, households cut spending on “things that are closely tied to people’s well-being in the moment,” Noel says.

Given that entire swaths of the U.S. economy are shut down, there are fewer opportunities for households to spend the cash and unemployment benefits headed to their bank accounts. Some people will use the money to cover some or all of their rent and mortgage payments. But those government checks aren’t likely to boost GDP in an appreciable way as long as the places where people typically spend money remain closed. And if the economy reopens too soon, a deeper recession could follow.

“No one is going to movie theaters and sporting events,” says Noel. “I guess it would be conceivable that you could spend on something else, double up on groceries or buy stuff online. But from what I see, it doesn’t appear people are doing that.”

Check out the rest of our coverage of how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting the economy, education and mental health in the U.S.