In their working lives, reporters naturally concentrate on reporting — making calls, developing sources, conducting interviews and research, and finally writing. All this effort centers on getting stories and making sure they’re timely, accurate and compelling. In large news operations, be they print, online or broadcast, journalists know that after they submit their stories, their copy will normally go through an editor and potentially copyeditor before publication. The goal of these additional layers of attention is to ensure that stories are comprehensible, consistent and correct.

Today, however, many journalists work on their own or in smaller organizations without a layer of dedicated editors. Many large organizations have also seen significant staff cutbacks, and attention to fine detail has often suffered. So is it enough for reporters to simply submit or post a story and cross their fingers? No.

Whatever the size of your news organization, dedicating time to examine the grammar, spelling, formatting and accuracy of your stories is essential. Copyediting is a very different activity from writing, and putting on an editor’s hat helps you see your own copy in a different way, and thus will help you improve it. Copyediting can even reveal deeper errors within a story that can send you back into your reporter’s role.

Every copyeditor’s approach is different, but it helps to work from the top down:

- Verify all factual assertions in your article. Double-check all names, even if you think they’re right. If you use a number or a date, no matter how seemingly insignificant, check it.

- Verify all math, especially averages and percentages. Check your units — thousands, millions, billions and trillions — particularly if you did any conversions. If you delve into statistics, double-check your work and terminology.

- If you make assertions about an individual or organization, did you contact them to verify the information and get comment? If not, do so, and don’t be satisfied with sending off an email. Exercise due diligence here.

- Do a complete read of the story from beginning to end. Does it flow easily and logically? Are the conclusions supported by the facts presented? As a reader, does the story leave you asking questions that could have been answered? Do you use technical terms that aren’t explained or jargon that’s unclear? Are there any run-on sentences or words you use too frequently? Address all these issues.

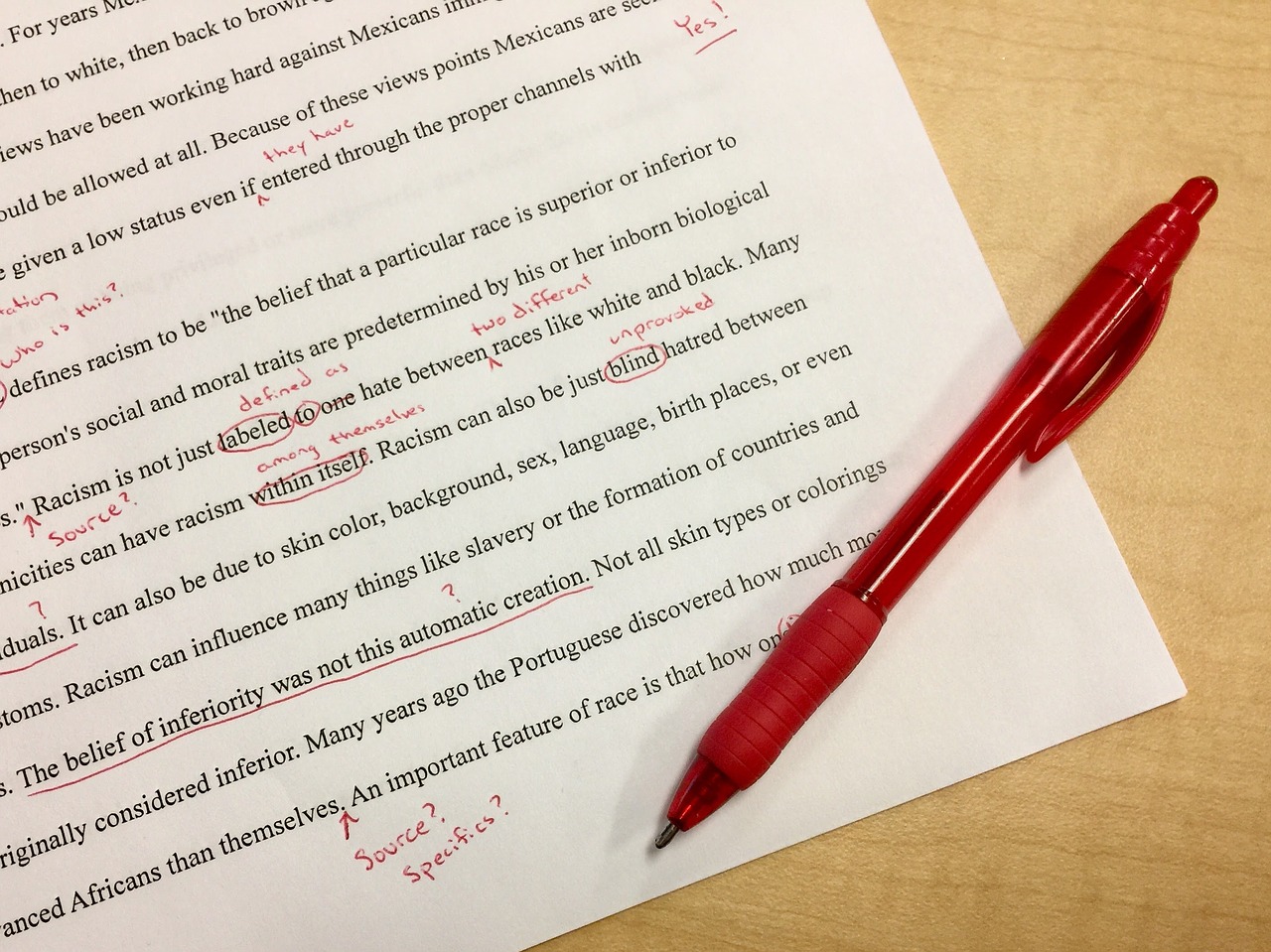

- Go through the story again, this time looking at each sentence individually and the words within each sentence. One helpful trick is to print out the story and read it with an index card blocking all lines below the one you’re reading; that way your eyes can’t skip forward until you’ve verified everything.

- As you go, check spelling with your preferred dictionary, and remember that while useful, spell-checkers aren’t always your best friend — for example, the words their, there, and they’re can be properly spelled in a sentence, and yet be completely wrong in context. The same goes for your and you’re; role and roll; sew and sow; and break and brake. Carefully ensure that quite, quiet and quit aren’t exchanged, and the same for through, though and thorough.

- Look at parentheses for correctness and consistency: If you see an open parenthesis, skip forward to ensure that there’s a closing one. Verify that periods are inside the final parenthesis for complete sentences and outside for incomplete ones.

- Do the same for quotation marks, verifying that they’re always properly paired. Make sure that quotes within quotes are singles, and that periods are inside the final quotation mark.

- Check all single-character punctuation as you go — commas, semicolons and colons, ellipses, percentage signs and apostrophes. Pay particular attention to ensuring that em-dashes are consistent, both in terms of the character used and the presence or absence of spaces on either side. If your chosen style uses percentages signs, ensure you’re consistent.

- Finally, if at all possible, have a colleague or friend carefully read a printed copy of your story, using the same index-card method. As careful as one person can be, it’s always good to have a second reader. Have that person mark up your copy, then verify and enter the changes yourself — it’s the best way to be forced to see things you missed, literally.

This is an involved process, but every step has a purpose. Separating the copyediting process from reporting and writing ensures that time is dedicated to each one. As you get used to copyediting your own work, you’ll become faster and your stories will get better. One helpful strategy is to keep track of the corrections you make and compile them in a “cheat sheet” — for example, it could remind you to check its versus it’s if that’s an error you tend to make. If you’re not feeling secure in your choices, take Poynter‘s free online course “Cleaning Your Copy.”

A good resource for copyediting is The Chicago Manual of Style. The AP Stylebook doesn’t attempt to address grammatical questions, so it is less helpful, but if it’s all you’ve got, use it. Note that whatever style you use, the key is to be not just correct, but also consistent. For example, there’s only one correct way to spell the word journalist in English, but catalog can also be spelled catalogue. (AP prefers the former.) Whatever the choice you make, stick with it, be it a matter of spelling, grammar, capitalization, case or style.

Even if you’re on deadline, it’s essential to dedicate time for copyediting. As the introduction to the “Cleaning Your Copy” course says: “Mistakes in grammar, spelling and style are like coffee stains on a shirt. Readers notice. And, eventually, those mistakes eat away at your credibility as a journalist.”

Related research: A 2014 study in Digital Journalism, “Audience Perceptions of Editing Quality, Assessing Traditional News Routines in the Digital Age,” examines the potential role of story editing in readers’ perceptions of the news quality and value. The author, Fred Vultee of Wayne State University, found that on average, study participants gave higher ratings to stories that had been edited than those that hadn’t. Careful editing had a consistent and positive effect on perceptions of story professionalism, organization, writing and value. “This outcome is not significantly affected by [participant] age, suggesting that these measures of quality are not traits that the lay audience needs to be taught before entering the news market,” Vultee writes, supporting “the idea that the appreciation of quality survives, regardless of the willingness to pay.”

Tags: training, copyediting