From the Scholars Strategy Network, written by Frank Seth Levy, MIT; and Richard J. Murnane, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Scary projections portray computerized robots taking over from humans, leaving Americans in the future with little gainful work to do. Yet the real challenge posed by computerized work is not mass unemployment, so much as the need to educate many more young people to do the jobs computers cannot accomplish. Meeting the true challenge America faces begins by recognizing that computers still have specific limitations compared to well-educated human beings.

What computers do — and still cannot accomplish

All workplace tasks require processing information, and computers can out-perform humans at highly structured tasks. These are tasks with well-defined information requirements that follow step-by step procedures — such as moving a robot arm between fixed points, rather than weaving through a crowded room to select an apple from a bowl of fruit. As they speed up and store information cheaply, computers are doing more. But many less-structured tasks in today’s workplaces remain beyond their reach.

Flexibility is the human mind’s strength — the ability to collect and integrate many kinds of information to accomplish a complex task. Many cognitively challenging professional and managerial jobs fit this description. So do others with no foreseeable step-by-step solutions, including manual jobs like moving furniture into an apartment. Also easy for people and hard for computers are such low-wage jobs as personal care, food preparation, and cleaning buildings.

The changing U.S. labor market

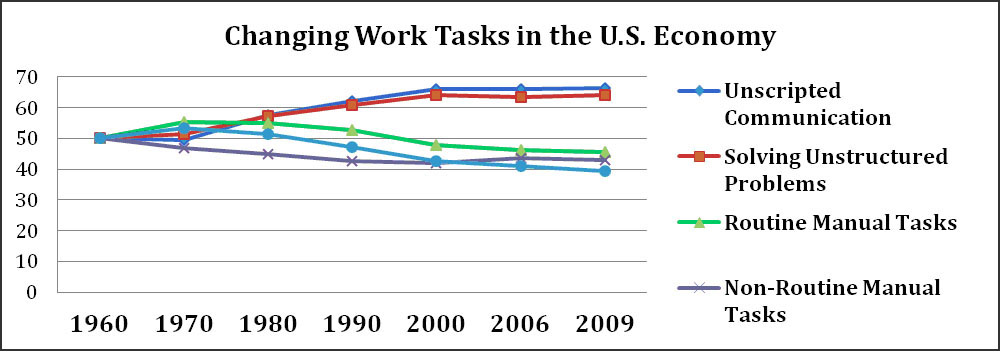

We have teamed up with David Autor to portray labor market trends since 1960 — a period when previously well-paid manual and clerical jobs have been computerized or offshored to other countries, while jobs calling for human ingenuity to solve unstructured problems proliferate.

America’s educational challenge

The fact that humans still do many things better than computers does not mean everything is rosy for workers today and tomorrow. Computerized work has ratcheted up the basic skills people need to master. Consider literacy. Forty years ago, reading well enough to follow directions was sufficient. Today a truly literate worker must be able to conduct an Internet search and quickly discern which of thousands of responses provide useful information. Literacy also includes the ability to make sense of fresh information as unanticipated problems are encountered.

Although often criticized, U.S. schools are actually not preforming worse. Results from long-term assessments show that most American students now master foundational skills — as those skills were defined four decades ago! Students can read well enough to follow instructions, for example. But of course past standards are not good enough now, because more complex foundational skills must be mastered by young people who need to navigate the twenty-first century economy. In addition, U.S. schools must make up for the deficits many children suffer when they spend their early years in families with low incomes or overstressed single parents. Too many American children enter school unprepared to learn.

Vocabulary is a case in point. Literacy today builds from a strong and nuanced vocabulary, and we know that children start learning words from their earliest years. Well before starting kindergarten, children from different economic backgrounds have very different levels of vocabulary — and these gaps largely persist throughout the school years, leaving many young people unready to do better than computers.

Teaching today’s foundational skills requires an emphasis on helping youngsters gain conceptual understanding and solve problems — an instructional goal especially difficult to accomplish in schools serving high concentrations of poor children. Unfortunately, the United States has an increasing number of such schools, where most pupils are poorly prepared and both students and teachers move in and out, leaving classrooms with little stability.

Preparing people to dance with robots

The recent development of Common Core State Standards holds significant promise for improving American education. If successfully implemented, the new standards can set clear goals for teachers and school administrators, and regular assessments can show how well students are mastering today’s crucial skills. As educators move forward with this approach, however, much more must be done to improve not just what schools try to teach, but also the training of teachers. What is more, states and school districts will have to persist with the new standards, even in the face of political pressures to go back to less demanding ones.

Computerization, in short, is having a profound impact on American life. Most Americans enjoy the new products and services brought by technological advances, but those same advances are eliminating many formerly well-paid jobs and increasing the need to teach all children and youth the skills required by expanding occupations. The extent to which the United States meets this new challenge will determine whether the longstanding American dream of upward mobility remains part of the nation’s future — and not just a fondly remembered part of its past.

Related research: For more information on this topic, see Levy and Murnane’s analysis in The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Creating the Next Job Market.

The authors are members of the Scholars Strategy Network, where this post originally appeared.

Keywords: research brief, technology