Banks consider lots of factors when determining if a mortgage applicant is a good credit risk. Race can’t be one of them — but that wasn’t true before the Fair Housing Act became law in 1968.

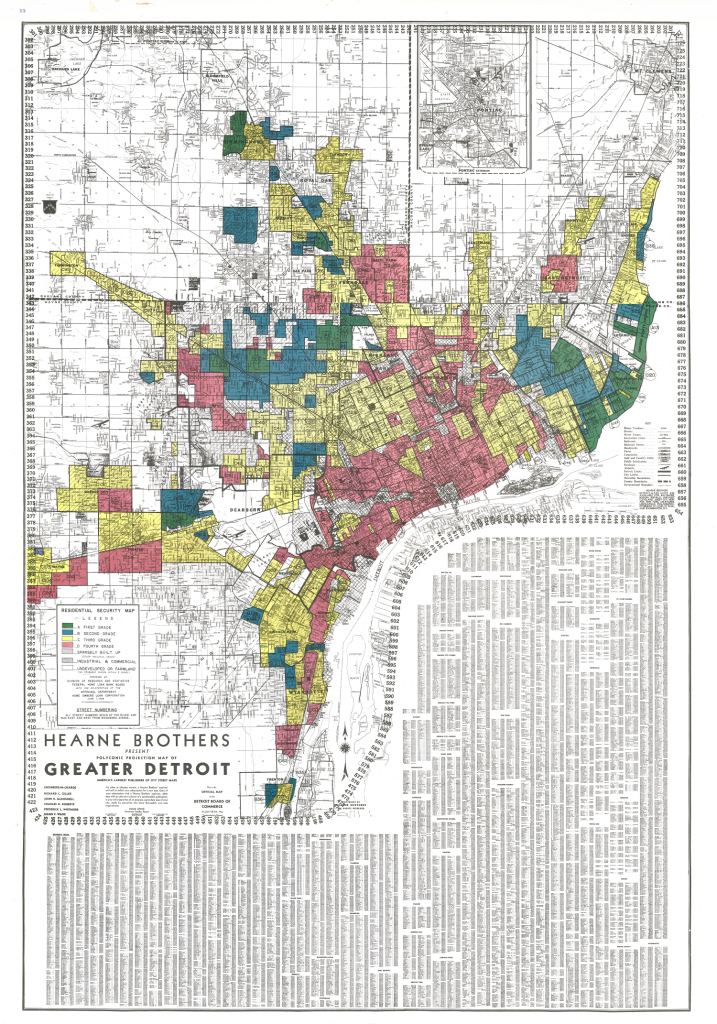

Redlining as an official government practice began with a now-defunct government-sponsored agency that created residential security maps in the 1930s. The agency filled in red the neighborhoods it determined to be the most risky for home loan prospects. These were usually black neighborhoods. Or, white neighborhoods near black neighborhoods.

New insight from a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper suggests that even without federally sanctioned redlining, areas of major U.S. cities that shifted from white to black during the 1930s would have suffered economically. Many black families faced a double whammy of soaring rental prices and plunging home values as they moved from the American South to cities in the North and Midwest.

From 1930 to 1940, rental prices increased 40% in areas that went from white to majority black, relative to areas that stayed white, according to the paper. The authors surmise from historical accounts that white investors purchased rental properties in black neighborhoods and that some white homeowners moved but continued to rent their homes.

“Both considerations underscore the fact that in our setting the owners of rental properties were most likely white,” the authors write.

At the same time, home values fell by more than half in areas that went from white to majority black in cities that were major landing spots for black families during the prewar years, including Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit — relative to areas that stayed white.

“In the Depression everyone’s home lost value, but our point is homes in neighborhoods that underwent racial transition lost way more,” says Allison Shertzer, associate professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh, who co-authored the paper with Prottoy A. Akbar, Sijie Li and Randall P. Walsh.

Intergenerational impacts on wealth growth

Wealth equals assets minus liabilities. As a simple example, a family that owns a $100,000 home and has $10,000 in credit card debt has wealth totaling $90,000.

Median wealth for white families was $171,000 in 2016, the most recent year available from the Federal Reserve, compared with $17,600 for black families. The difference is $153,400.

In Boston, the median net worth for black families is $8 according to a 2015 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Duke University and the New School — that’s not a typo.

Owning a home is a key way that Americans build wealth, including for low- and moderate-income households, and a generation of prewar black families saw their home values decline in major U.S cities.

“Housing is the most important asset for the vast majority of American households and a key driver of racial disparities in wealth,” the authors write. “These findings suggest that, because of the segregated housing market, black families faced dual barriers to wealth accumulation: they paid more in rent for similar housing while the homes they were able to purchase rapidly declined in value.”

A brief history of racist lending practices

After the turn of the 20th century, millions of black families in the U.S. started moving from the South to cities in the North. The first Great Migration happened from 1910 to 1940. One motivator was the glut of decent-paying jobs to build new mass-produced things, like cars.

The federal government officially began sanctioning racist home lending practices in the late 1930s. By 1936 the Home Owners Loan Corporation had drawn up its residential security maps, which outlined neighborhoods the agency determined had risky home loan prospects.

Without access to credit, many black neighborhoods deteriorated.

“If I try to move to opportunity, in our context from working in sharecropping in Jim Crow south, I move to Chicago and I’m earning more money and I have a less terrible job but then I see these dynamics in the housing market,” Shertzer explains. “So if I try to improve my circumstances by moving to a better neighborhood I see this play out over and over again. Essentially if you’re black in early-to-mid-century U.S. you can’t move to opportunity without paying out increased wages in the housing market.”

Racial segregation was not a side effect but a feature of federal housing policy around this time. From the 1938 Federal Housing Administration Underwriting Manual:

“Areas surrounding a location are investigated to determine whether incompatible racial and social groups are present, for the purpose of making a prediction regarding the probability of the location being invaded by such groups.”

It would be another three decades before the U.S. outlawed redlining. Many redlined communities still struggle today.

Research methods

The authors used Census tabulations from 1930 and 1940 covering nine major cities and two boroughs in New York City: Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn and Manhattan, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and St. Louis.

They call Baltimore, Cincinnati and St. Louis “border cities.” These cities are closer to the south and had large black populations by 1930. Boston, Brooklyn and Pittsburgh had fewer migrants during the first Great Migration, so they’re called “low-migration” cities. Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Manhattan and Philadelphia are called “high-migration” cities.

“You can do a real apples-to-apples comparison,” Shertzer says. “You can go look at the same house and it has white occupants [in 1930] and now [in 1940] it has black occupants.”

The authors built a dataset of 591,780 unique home addresses across 100,000 city blocks with an average of 10 to 15 addresses per block. They focused on blocks that changed from 95% white in 1930 to majority black by 1940.

“We are looking at city blocks, one section of one road located in a very specific geographic area,” Shertzer says. “Our control group is a block in that same neighborhood that does not undergo racial transition.”

By 1940, home values in transitioning blocks in high-migration cities were 54% lower than home values on blocks that remained white. Home values increased slightly on transitioning blocks in border cities, but rents on those blocks increased 86% relative to blocks that stayed white, driving the overall rental premium across the cities.

Though redline maps emerged in the late-1930s, Shertzer doubts they had much effect on the results.

“The number of HOLC loans was so small in our sample, it’s less than 1%, and even by the most generous estimation it’s stupendously unlikely the HOLC lending activity could be driving any of our results,” she says.

Topline findings

Here’s what the researchers determined by matching housing data from 1930 and 1940:

- In neighborhoods that shifted from white to majority black, rental prices increased 40%.

- Across cities, home values in blocks that transitioned to majority black fell on average by 10% compared to blocks that stayed all white.

- In high-migration cities — Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Manhattan and Philadelphia — home values on transitioning blocks were 54% lower than on blocks that stayed white.

- Home prices fell most on blocks that were more than 50% black by 1940.

- In border cities — Baltimore, Cincinnati and St. Louis — rents on transitioning blocks increased 86% compared to blocks that stayed white.

- Across cities, the capitalization rate — the income a property brings in compared to the property’s market value — was 17% on blocks that turned majority black compared to 11% on white blocks, meaning higher rents in black neighborhoods led to more relative profit for landlords.

Again, housing practices that spurred racial segregation began before redlining

Here’s one big takeaway for journalists: Prewar housing inequality is a complicated story and there were market forces at play before the federal government signed on to redlining.

“It’s not all about redlining,” Shertzer says. “Every interaction I’ve had with journalists the last 2 years has been like, ‘This is the legacy of redlining.’ And I try to explain what’s happening in the housing market. I think the most important thing for journalists is not to neglect the housing market dynamics and not default to, ‘It’s redlining,’ or, ‘It was the government.’”

She adds: “I know I’m swimming upstream on this but it’s something that’s really poorly understood. I’m not saying redlining doesn’t matter but the way that people understand it is not exactly right.”

Want more JR coverage on inequality? Check out how global warming has worsened economic inequality and made some rich countries richer and how high housing costs are associated with increased food insecurity, child poverty and a greater proportion of people in fair or poor health.