The summer employment rate for U.S. teens held steady at around 50% from 1950 to 2000, but began to decline dramatically in the 21st century. By 2009, it had fallen below 33% for those ages 16 to 19.

The decline has been most pronounced for more educated and economically advantaged teens, who appear to be moving away from paid employment in favor of voluntary work, perhaps to enhance their college prospects, or to fulfill high school graduation requirements.

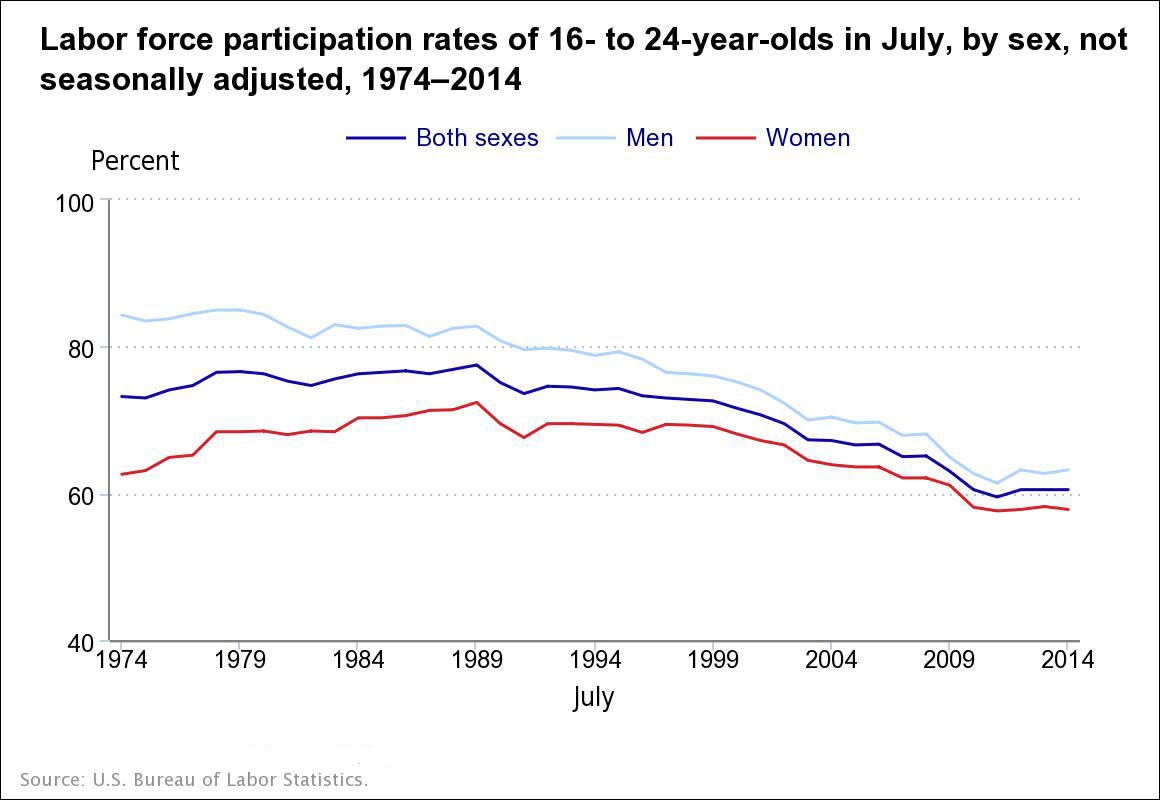

An analysis of a broader cohort of young people — those ages 16 to 24 — also reveals a steady decline, despite a slight uptick in employment over the past year. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics notes that the “July 2014 participation rate was 17.0 percentage points below the peak rate for that month in 1989 (77.5 percent).” (July is typically the peak of youth employment, and thus is used as a statistical benchmark.) Among those ages 16 to 24 working in July 2014, “25 percent of employed youth worked in the leisure and hospitality industry (which includes food services), and 19 percent worked in the retail trade industry. ”

While a reduction in teen summer employment may be a positive trend for some, there are significant costs for society as a whole. The White House Council for Community Solutions has identified around 6.4 million “opportunity youth” — young adults between the ages of 16 and 24 who are not enrolled in school and who are chronically unemployed or underemployed. The Council estimated the lifetime cost of underinvestment such youth at $4.7 trillion. A 2014 report from the Brookings Institution suggests a number of approaches to reducing youth unemployment, including expanding apprenticeships and linking high school to post-secondary educational credentials. Further, the erosion of opportunities for young people has hit minority teens particularly hard.

While the major benefits of summer employment may lie in gaining work experience and supplementing family income, it could also have educational implications. For example, having a summer job can increase teens’ time-management skills, motivation, self-confidence and sense of responsibility, all of which could help them succeed at school — but little academic research has been done on this question. Given that many cities invest in summer jobs programs for their youth, and such programs face budget constraints along with most other public spending, evidence of their positive educational impact would be an important contribution to policy and budget debates.

A 2014 paper published in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, “What Is a Summer Job Worth? The Impact of Summer Youth Employment on Academic Outcomes,” assesses the impact of New York City’s Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) on high school students’ attendance and academic performance the year after participation in the program. The author, Jacob Leos-Urbel of Claremont Graduate University, uses data for 36,550 SYEP applicants in 2007 matched to their New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) files. The only difference between applicants who were accepted by the program and those who were not was the assignment of a place through a lottery system.

The study’s findings include:

- SYEP participation increased school attendance by approximately 1%, or one to two school days per year. Broken down by semester, selection for the program increased attendance by around 1% in the fall and 2% in the spring.

- For students whose school attendance rate was 95% or lower prior to SYEP, the program improved their attendance by 1.6% in the fall semester and 2.7% for the spring semester.

- SYEP participation had no significant effect on the attendance rates of students who 16 or younger in the school year following the summer jobs program and had an attendance rate below 95% at the start of the study. For those 16 and older, SYEP increased school attendance by around 3%, the equivalent of four to five school days. As school attendance is only mandatory until age 16, it is consistent that the program would have a greater influence on those teens who have more ability to decide whether or not to attend school.

- Only 70% of those who win a place in SYEP go on to participate in the program. Looking at just those who did take part, school attendance increased 1.7% for all students, 2.6% for those with a low baseline of attendance, and 3.9% for those 16 or over with low prior attendance.

- The study also looked at the likelihood that SYEP participants would take the more rigorous Regents diploma exams rather than the local diploma. The results showed that SYEP participation modestly increased the likelihood of their doing so, but did not appear to improve the probability of their passing the exams.

- For students 16 and over with a low baseline of attendance, SYEP increased the likelihood that they would take and pass the Regents exam, but had no significant effect on exam scores.

- The number of students obtaining Regents diplomas rose, but this was not attributable to the SYEP improving students’ performance. Instead, SYEP increased the number of students taking the exams, which in turn increased the number who passed. Of the 7,533 students in this group who were selected by the SYEP lottery, an estimated additional 128 students passed the English Regents and 98 passed the math Regents.

One limitation of the study, Leos-Urbel notes, is that the data sheds little light on the underlying mechanisms that lead to increased academic engagement. For example, it could be that the SYEP increases participants’ confidence and self-esteem, or that the income from the program reduces the need to work during the school year and thus increases academic focus. Nevertheless, the results are not trivial: “Viewed within the context of school attendance policy, an increase of four to five days of school attended represents about one-quarter of the 18 total days that New York City students may miss and still be promoted to the next grade. Further, these effects are roughly on par with findings of recent experimental evaluations of interventions involving financial incentives (or disincentives) directly tied to school attendance.”

Related research: A 2014 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research explores the long-term benefits of early employment experiences. The increasingly unequivocal evidence of summer learning loss has been the subject of widespread public attention in recent years. A 2010 study in the John Hopkins New Horizons for Learning journal, “Why Summer Learning Deserves a Front-Row Seat in the Education Reform Arena,” reviews decades of evidence of a “summer slide” in education, with young people losing about two months of grade level equivalency in mathematical computation skills over the summer. More importantly, those from low-income households lose more than two months in reading achievement, while their middle-class peers make slight gains.