In April 2014 the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced that the number of U.S. private-sector jobs had finally returned to their 2008 peak — six long years ago, and after an achingly slow, four-year recovery. A 2013 report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS) indicated that in October 2006 unemployment was only 4.4%, but by 2009 had hit 10%. It has since dropped to 6.7%, but openings can remain stubbornly hard to find. Many groups have been hard hit, from veterans to recent college graduates, and for the long-term unemployed, job searches can stretch on endlessly.

The U.S. economy is expected to add approximately 200,000 jobs a year, but those added aren’t necessarily the same as the ones that were lost six years ago. Ongoing technological and economic change, including computerization and offshoring, have led to a significant recomposition of the U.S. labor market. A 2013 study from Duke and the University of British Columbia, found that during recessions, middle-income jobs are hollowed out at rapid rates.

A 2014 analysis of BLS data by the National Employment Law Project (NELP), “The Low-Wage Recovery: Industry Employment and Wages Four Years into the Recovery,” takes a close look at the types of jobs that were lost during the recession and those that have been added since the recovery began. Source data came from the BLS’s Current Employment Statistics (CES) and Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) surveys. Wage data came from the OES, which provides median estimates rather than averages, which can be distorted by higher-wage occupations within certain industries.

The study’s findings include:

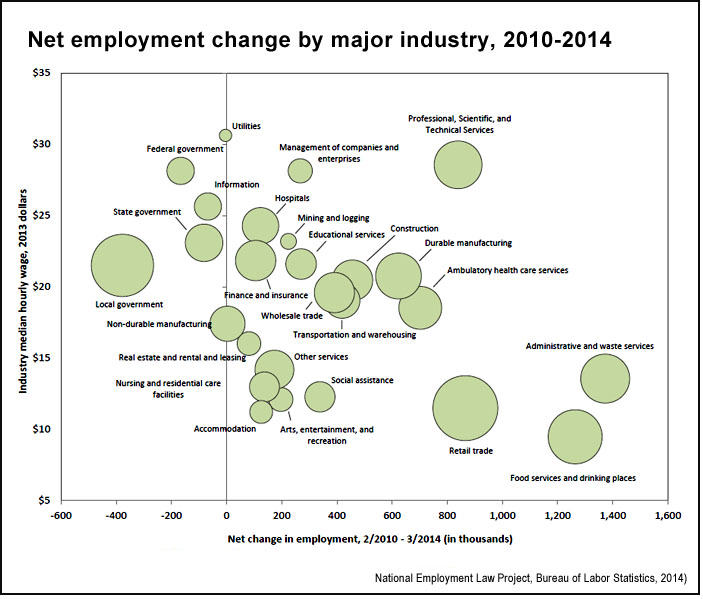

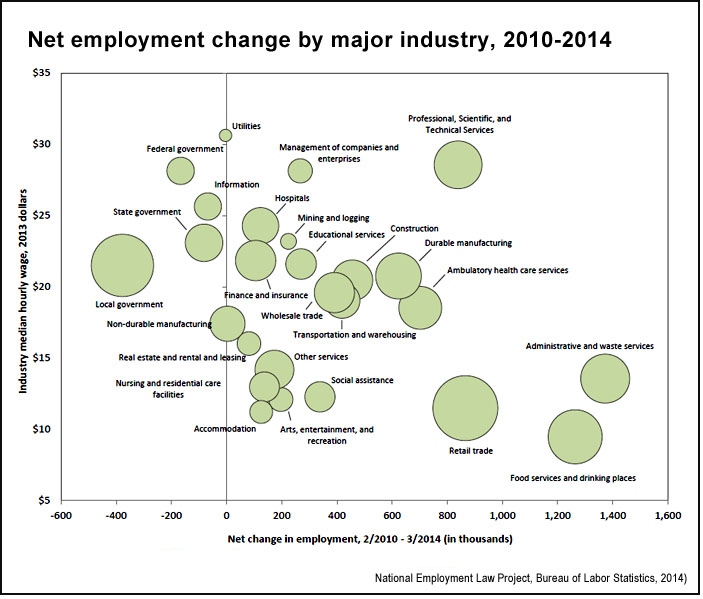

- While the U.S. economy has now returned to the absolute number of private-sector jobs it had in 2008, the losses and gains have not been evenly distributed: High-wage industries lost 1 million positions, while low-wage jobs gained 1.8 million. As shown in the chart below, the recession’s impacts vary widely, but overall, losses were larger in high-wage jobs and growth stronger in low-wage work.

- Lower-wage industries accounted for 22% of job losses during the recession, but 44% of employment growth since the recovery started. The lower-wage sector lost 2 million jobs during the recession, but has since added 3.8 million.

- Food-service work, the lowest-paying of the low-wage work at a median hourly wage of $9.48, showed the most growth by far: While 367,000 positions were lost during the recession, 1.2 million have been added since. Overall, the sector employs 9% more workers than it did before the downturn.

- Other low-wage growth industries include health and education: “Relatively immune to downturns, this was the only sector to add jobs over both the downturn and recovery, pushing employment nearly 13% higher than it was at the start of the recession.”

- Mid-wage industries accounted for 37% of jobs lost during the recession, but only 26% of positions added since. There are now nearly 1 million fewer such jobs than in 2008. Local government services were particularly hard hit, and have yet to fully recover.

- Higher-wage industries accounted for 41% of jobs lost during the recession, but only 30% of new jobs. During the recession, 3.6 million positions in higher-wage industries such as accounting, legal work and construction were lost; only 2.6 million such positions have since been added.

- Significant gains were seen in the high-wage professional, scientific and technical services industries, adding more than 800,000 jobs through March 2014 — occupations such as accountants, legal professionals, software developers and engineers. However, “while strong job growth in this higher-wage industry is a positive development, the employment increase is over six percentage points less than it was at a similar stage following the 2001 recession.”

- While there has been some recovery in construction, manufacturing, transportation and related occupations, the recession losses were sufficiently large that they are only now returning to pre-recession levels — construction employment is still 20% below the 2008 high, for example, while food and textile manufacturing is still 11% lower than at the start of the recession.

- “Over the past four years, private-sector gains have been partially offset by public sector job losses resulting from budget cuts at the federal, state, and local levels. Net job losses totaled 627,000 across all levels of government during the recovery period. Employment declines were particularly severe at the local level, where education absorbed nearly three-quarters of the 378,000 net job losses over the past four years.”

- The 2001 and 2008 recessions displayed different patterns of job losses and gains: After the 2001 recession, 39% of the gains were in lower-wage industries, approximately 20% were mid-wage and 40% were higher-paying. After the 2008 recession, growth has been concentrated in low-wage industries and some mid-wage ones, but higher-wage growth has been much weaker.

The study’s author, Michael Evangelist, in an interview with the New York Times, said: “Fast food is driving the bulk of the job growth at the low end — the job gains there are absolutely phenomenal. If this is the reality — if these jobs are here to stay and are going to be making up a considerable part of the economy — the question is, how do we make them better?”

Related research: A 2014 review by the Pew Research Center also looks into the Bureau of Labor Statistics data to examine the role of geography in long-term unemployment. They cite research that supports the existence of a “spatial mismatch” between job seekers and jobs: “Living near where the jobs are significantly reduces the amount of time it takes unemployed jobseekers to find work. The research found that to be especially true for blacks, women and older workers.” Also of interest is a 2014 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), “Declining Migration within the U.S.: The Role of the Labor Market.” It explores why internal migration in the United States has decreased steadily since the 1980s. The scholars, at the Federal Reserve and University of Notre Dame, find that a significant driver of the trend is the “decrease in the net benefit to changing employers” — new jobs offer lower wages or other benefits than old ones did, so moving is less attractive.

Keywords: recession, unemployment, inequality, financial crisis, jobless recovery, offshoring, computerization