While a new Ebola outbreak makes headlines, another much more extensive epidemic is quietly spreading across the world: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB). The World Health Organization estimates that there were 490,000 new cases of the disease in 2016, which represents a slight increase from 2015’s estimated 480,000 new cases. By contrast, a 2016 WHO situation report on the Ebola virus notes a total of 28,600 cases in West Africa.

Though tuberculosis is a curable disease, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis presents an especially dire threat because, as the name suggests, the most powerful TB drugs don’t work to treat it. These drugs, isoniazid and rifampin, are typically given to all tuberculosis patients. Because these preferred drugs don’t work on MDR TB, though, treatment options are limited and mortality rates for the disease are much higher than for treatment-responsive tuberculosis. A World Health Organization report indicates that only 54 percent of MDR TB patients are successfully treated, compared to 90 percent treatment rates for conventional tuberculosis.

Worse yet, there is another strain of tuberculosis that’s also resistant to the drugs given when these most commonly administered drugs fail — so called “second-line” treatments. Extensively drug resistant TB (XDR TB) is additionally resistant to fluoroquinolone and either amikacin, kanamycin or capreomycin. Treatment rates for XDR TB stand at 30 percent. XDR tuberculosis is spreading as well; in South Africa, the number of cases increased by a factor of 10 between 2002 and 2012.

As the threat of MDR TB and XDR TB continues to grow, Journalist’s Resource has gathered information for reporters looking to learn more about the global epidemic.

What is tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis starts as a bacterial infection that can develop into a serious disease that commonly affects the lungs. Most people infected with TB never get sick and cannot transmit the disease; this is called latent TB infection. Worldwide, about one-quarter of the population has latent TB. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that among those untreated, between 5 and 10 percent infected with TB develop the disease. Symptoms include a serious cough, which can sometimes bring up blood or phlegm, as well as chest pain, weakness and fatigue.

How is it spread?

TB is spread from person-to-person through the air. When a person with active TB coughs (or sneezes, or talks), this expels the bacteria from their lungs or throat. Bystanders might then breathe in these airborne droplets and develop TB infection. TB spreads mostly among those in close contact with people who have the disease. Because it’s transmitted through air, though, it’s more contagious than some other diseases, like Ebola, which requires direct human-to-human contact for transmission. Historically, TB was a widespread problem. Sometimes called consumption, it ravaged populations globally in the early 20th century, accounting for one of every seven deaths in the United States and Europe. In the 1940s and 1950s, scientists discovered drugs to treat the disease and its prevalence declined.

Tuberculosis today

In the 1980s, TB experienced a resurgence in the United States, due in part to the increased susceptibility of individuals infected with HIV, an influx of cases through immigration and reduced resources aimed at prevention and treatment.

TB cases in the U.S. have since declined (in 2017, there were about 2.8 cases per 100,000; it’s worth noting, however, that TB disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S.).

Globally, however, TB is currently the ninth leading cause of death. More than 10 million people became sick with TB in 2016 and nearly two million died. Over 95 percent of these deaths were localized to low- and middle-income countries.

“As case rates dropped in wealthy countries, funding for research and implementation programs dried up, even though tuberculosis remained the world’s leading infectious killer of young adults throughout the 20th century,” physicans Salmaan Keshavjee and Paul Farmer wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012.

They continue, “By the early-to-mid-1990s, MDR tuberculosis had been found wherever the diagnostic capacity existed to reveal it.” Tuberculosis bacteria, like other bacteria, can, through the processes of mutation and natural selection, develop resistance to available treatments. But the funding and the force needed to mitigate the spread of MDR TB just hasn’t happened in low- and middle-income countries. “Instead, selective primary health care and ‘cost-effectiveness’ have shaped an anemic response to the ongoing global pandemic,” Farmer and Keshavjee conclude.

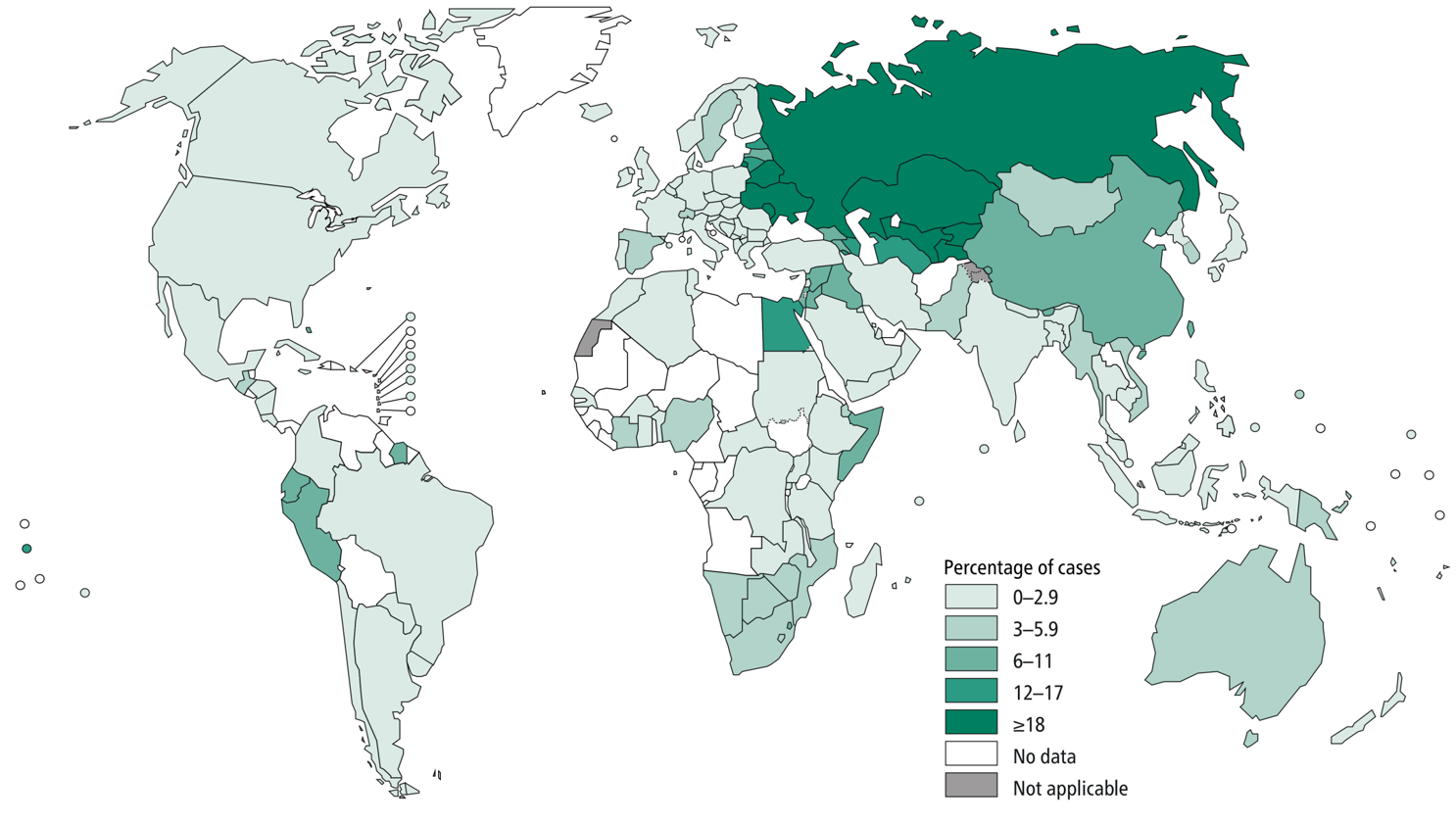

Where does MDR TB pose the greatest threat?

Many of the countries hit hardest by MDR TB are in Africa, but countries in Eastern Europe and Asia also are included. The World Health Organization produces an annual global tuberculosis report, which highlights the countries facing the highest burdens in the context of TB in terms of both absolute numbers of cases and case rates per capita. According to CDC data, only about 1 percent of TB cases in the U.S. are multidrug-resistant.

What’s the future outlook for MDR TB?

Research published in The Lancet in 2017 predicts the incidence of MDR and XDR TB from 2000 to 2040 in India, the Philippines, Russia and South Africa — four countries with high burdens of MDR TB. The paper indicates that in each of these countries, the percentage of TB cases that are resistant to multiple drugs will increase. In Russia, the model estimates that by 2040, 32.5 percent of cases will be multidrug resistant. MDR TB would make up 12.4 percent of cases in India, 8.9 percent of cases in the Philippines and 5.7 percent of cases in South Africa.

Is there any way to treat it?

Another study published in the Lancet in 2017 looks at the history, transmission and epidemiology of MDR and XDR TB, along with treatment options. There are regimens to treat these resistant forms of the disease, which generally involve a combination of drugs — the WHO recommends the use of at least five. Such aggressive protocols can entail “significant toxicity and pill burden, poor adherence, and 6–8 months of painful injections,” according to the Lancet study. A shorter regimen has shown promise in patients who have not yet received second-line TB treatment.

The other side of the coin: Prevention

A 2017 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine indicates that to control the wider epidemic, efforts must focus on prevention. The study looked at cases of extensively drug resistant TB in South Africa. “The majority of cases of XDR tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, an area with a high tuberculosis burden, were probably due to transmission rather than to inadequate treatment of MDR tuberculosis,” the authors write. Treatment, of course, is a part of prevention. “Halting transmission requires identifying and separating infectious patients, improving ventilation in congregate settings, and promptly initiating of effective treatment.”

Other prevention strategies include “political commitment to national programs designed to control disease by means of early diagnosis with the use of bacteriologic testing, standardized treatment with supervision and patient support, and provision and management of the drugs used in treatment,” according to a 2010 review published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Rapid testing for drug-resistant TB is another strategy that can help reduce transmission by hastening the identification and treatment of MDR and XDR TB.

There is a vaccine that protects against TB in children, called bacille Calmette-Guerin or BCG. “It is expected that the effectiveness of BCG against XDR-TB is similar as for ordinary TB,” the WHO indicates. The vaccine is not as effective in adults.

Journalist’s Resource has also put together a tip sheet on covering epidemics and covered research on the economic costs of drug resistant infections and trends in overprescribing antibiotics.

Graphic obtained from the World Health Organization and used under a Creative Commons license.