Big cities dominate America’s cultural consciousness in ways that the countryside — amber waves of grain notwithstanding — can only dream of: Manhattan skyscrapers, L.A. movie stars and Chicago’s “big shoulders,” as Carl Sandburg put it in his 1916 poem. Cities can have political power, too, embodied by recently departed but long-serving mayors such as Boston’s Thomas Menino (21 years), Chicago’s Richard M. Daley (22 years) and New York’s Michael Bloomberg (12 years).

Where their political power often ends is at city limits, however, and often it doesn’t even make it that far. Metropolitan areas lack the ability to legislate on their own behalf, and so require state approval to achieve many goals. Despite significant representation in state assemblies, they can still have difficulty moving their legislation forward. For example, Bloomberg had to work for years to be granted permission for just 20 speed cameras on New York streets, and things aren’t shaping up to be any easier for the city’s new mayor, Bill de Blasio. One of his campaign promises was to fund pre-kindergarten education with a tax on wealthy residents, but to do so he has to get past the governor, Andrew Cuomo, who has pledged to cut taxes.

While these and other issues demonstrate the legislative difficulties large metropolitan areas face, the reasons are less clear. Small-town hostility toward big-city immigrants, partisan divisions, or racial antagonism are often cited, but hard evidence is lacking. (Simple rural-urban animus is also suggested, but that’s too imprecise to be meaningful.) A 2013 study published in the American Political Science Review, “No Strength in Numbers: The Failure of Big-City Bills in American State Legislatures, 1880–2000,” examines the question by looking at 120 years’ worth of “district bills” in 13 state assemblies. Such bills directly affect counties, cities, towns and villages, as well as school districts, parks, airports, highways and other identifiable places. In all 1,736 pieces of legislation were considered.

In their research, the scholars — Gerald Gamm of the University of Rochester and Thad Kousser of the University of California, San Diego — consider five possible explanations for cities’ relative lack of political power: divisions within large delegations; hostility against cities with large populations; prejudice against cities with significant numbers of immigrants or African American residents; partisan divisions; and, finally, the possibility that the sheer number of big-city bills could reduce overall success rates. The states examined were Alabama, California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New York, Texas, Vermont, Virginia and Washington.

The study’s findings include:

- District bills introduced by legislators from big cities — defined as localities with populations of 100,000 or more — fail at significantly higher rates than those for towns and rural areas. “Year after year, while most bills affecting smaller districts pass, most big-city bills fail.”

- Cities with populations between 10,000 and 100,000 had the best success with district bills, 64%. As population grows, success rates fall: Those between 100,000 and 500,000 saw only 42% of their legislation pass, while cities over 500,000 had the lowest rate, 32% — half that of cities one-fifth the size or smaller. “This finding is not spurious,” the authors write. “It cannot be explained away by differences in bill content or bill authorship, or by a crude bias against the single largest city in a state.”

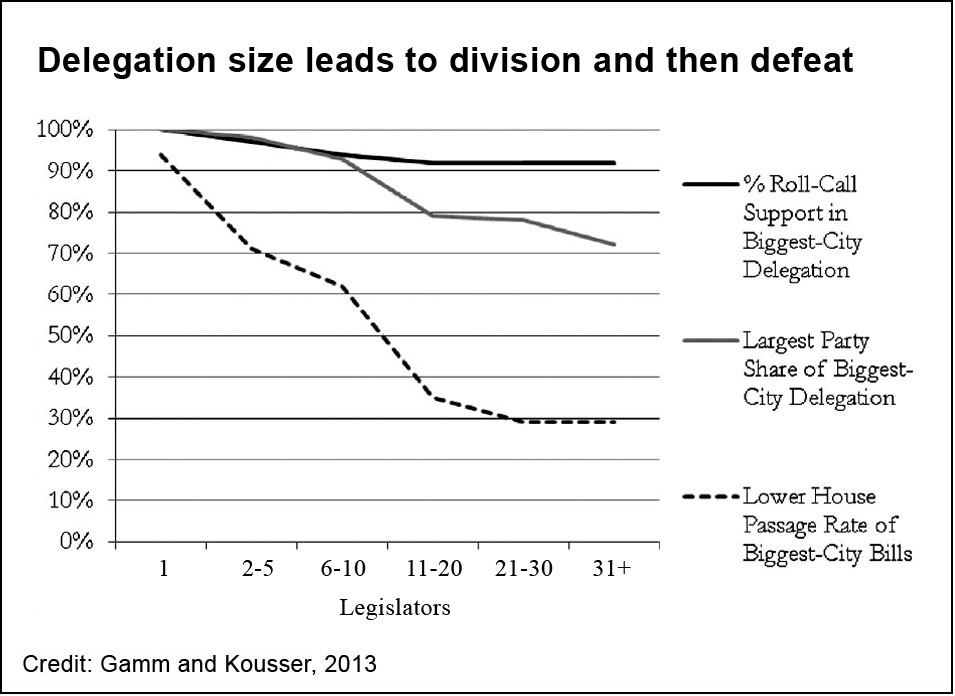

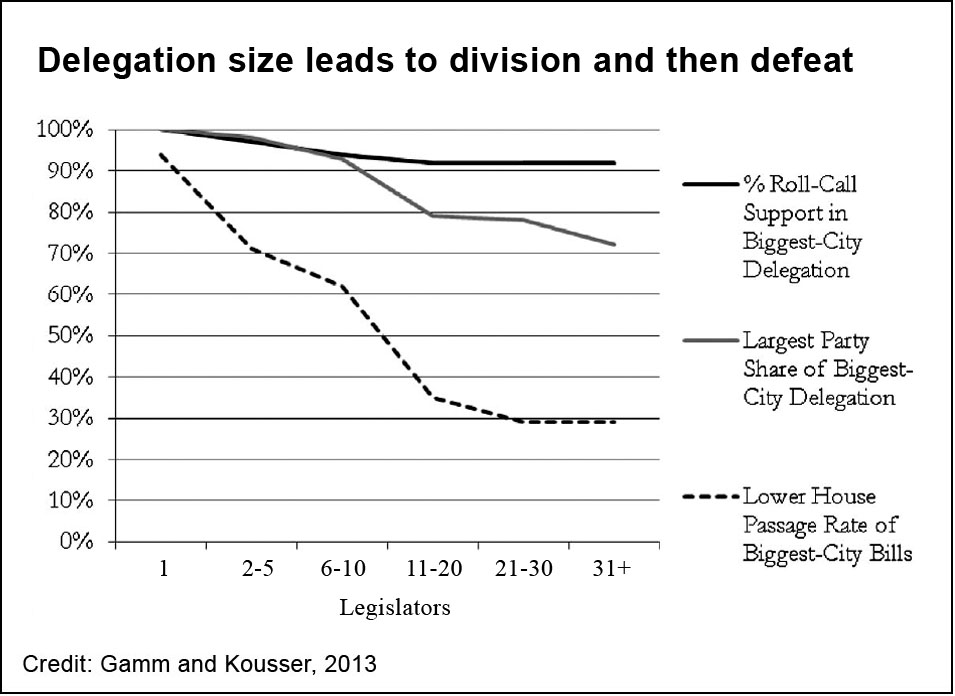

- Cities with the largest delegations had the highest failure rates for district bills. The larger the delegations are, the more likely they are to be internally divided, and the less likely their bills are to pass. “The changes in passage rates are smooth and consistent across each step of increasing delegation size — from 95% for bills introduced by one-person delegations to 29% for bills introduced by the largest delegations.”

- The larger the proportion of foreign-born residents in a city, the more likely its district bills would go down to defeat in state assemblies. This “helps explain why bills from cities such as New York and Chicago, hubs of immigration relative to the rest of their states, fare more poorly than bills from cities such as Richmond and Minneapolis, which are microcosms of their states.”

- A city’s percentage of African American residents was found to not be a significant factor, nor was the race of its mayor. “We probed for other potential impacts of race or ethnicity, but found no evidence that it was an important obstacle to big-city [legislative] success.”

- Partisan divisions between large cities, smaller towns and rural areas were also found to play no role, nor was the large number of bills introduced by big-city delegations a factor.

“Overall, the major lessons of this analysis are that cities lose in the statehouse when their residents appear foreign to other state legislators and when their delegations are too large to speak with a unanimous voice,” the researchers conclude. “Other measures of hostility — party divisions, bills introduced by members of the minority political party, large African American populations, many rural legislators — have no effect on passage rates.”

Taken together, the results explain why, in particular, district bills from cities such as New York, Chicago, and Detroit have little success: “Legislation from a city is more likely to lose when that city’s legislative delegation is large and when the city houses many more immigrants than the state.” Difficulty thus comes from both internal and external factors: Large delegations lead to divisions, while large immigrant populations are perceived with hostility.

Related research: A 2012 paper from the Harvard Kennedy School and Singapore Management University, “Isolated Capital Cities, Accountability and Corruption: Evidence from U.S. States,” explores why geographically remote state capitals such as Albany, New York; Springfield, Illinois; and Trenton, New Jersey, might be more susceptible to political corruption than big-city capitals. It finds that there is a robust “empirical connection between isolated capital cities and greater levels of corruption across U.S. states.” This “holds with different measures of corruption, and different measures of the degree of isolation of the capital city.”

Keywords: partisan divide, rural, corruption, @leightonwalter, @journoresource