Any discussion of tax reform in the United States eventually turns to entitlements. These costly benefits include Medicaid and Medicare, health insurance for the poor and elderly, and Social Security, America’s public pension program. Social Security alone accounts for about 25 percent of all federal spending.

Fifty-nine million Americans receive regular Social Security payments. Workers generally start receiving checks in their mid-60s and are eligible until they die. As the number of beneficiaries grows (and they live longer), the program faces an urgent shortfall. It has been running a deficit since 2010.

Reforming Social Security is not just a matter of rewriting the federal budget. These payments are mandated by law. Any adjustment must be legislated. To save the program in its current form, taxes need to rise or funds found somewhere. But hiking taxes is a challenging task in a Congress riven by partisanship, where hundreds of lawmakers have taken an oath not to raise taxes.

It may be little wonder, then, that a 2014 Pew Research Center poll found that half of Millennials and Generation Xers do not believe they will receive Social Security benefits when they retire.

How Social Security works

President Franklin Roosevelt founded Social Security in 1935 to provide a basic income for the aged and disabled. The program is financed with a dedicated payroll tax: The more you put in, the more you receive in your golden years (the payments rise with inflation). It is a transfer of wealth from the younger to the older.

The reserves are managed by the Social Security Administration, an independent federal agency, in two trust funds: The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance fund (OASI), which disbursed over $700 billion to 48 million Americans over age 65 and their surviving spouses in 2015, and the Disability Insurance fund (DI), which paid 11 million beneficiaries $142 billion that year.

The DI is in worse shape, according to numbers from the Social Security Administration. In 2015, President Obama signed a bipartisan act that allowed the DI to receive a larger portion of tax revenues for several years. Still, most estimates project it to become insolvent first.

An aging crisis

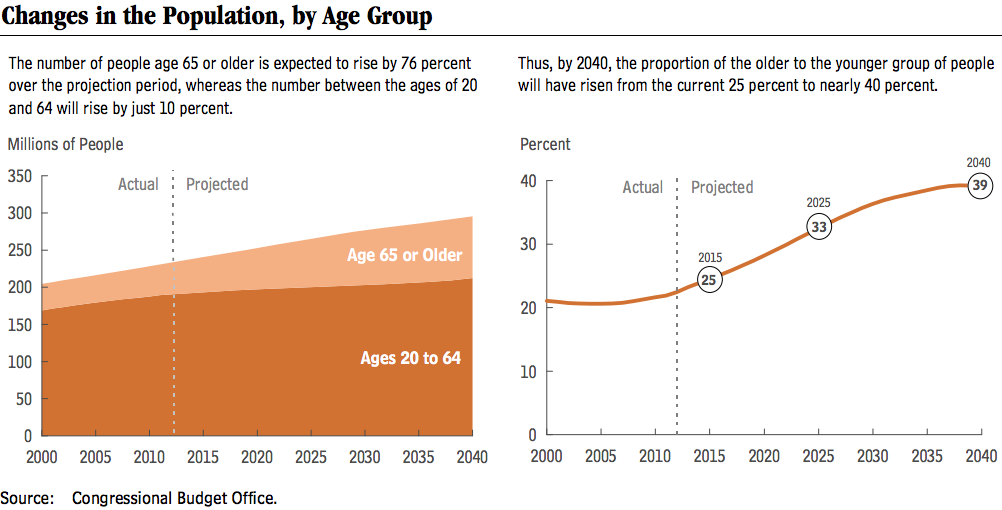

A few simple statistics about America’s aging population show why Social Security is facing a long-term crisis. For starters, the number of OASI beneficiaries grew 15 percent from 2009 and 2014; the number of people over age 85 grew 9.5 percent. Meanwhile, over the same period, the number of workers paying into the program grew only 6.4 percent. As in many rich countries, the proportion of older people to the young is growing fast.

In the 1980s, Congress raised the Social Security tax to support baby boomers who would be retiring in upcoming decades. That helped create a surplus. But by 2010, payments began surpassing revenues. In 2015, the program ran a $70 billion deficit. The trustees of the Social Security Fund (six senior federal officials) estimate the program will become insolvent in 2034; the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says that will happen by 2029. In either case, benefits will be reduced. The CBO estimates benefits will fall 29 percent in the first year — so if your grandmother expects a $1,000 monthly check, she would receive $710, instead.

Inequality

Researchers have shown that wealthier people enjoy the most gains from increases to life expectancy. They are also draining the Social Security trust fund at a faster rate.

The Social Security Act mandates that because the rich pay more tax during their working years, they receive higher payments in retirement. An April 2017 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research explores how the divergence in life expectancy may perpetuate economic inequality and undercut the Social Security program’s solvency. For example, if someone receiving $2,000 in monthly payments lives to be 85 and someone receiving $1,000 per month lives to be 75, the wealthier person receives $120,000 more ($1,000 x 12 months x 10 years).

Moreover, workers pay Social Security tax on their first $127,200 of income (this “taxable maximum” increases with inflation). As wage inequality in the U.S. has grown (meaning that the top earners take a bigger part of the income pie and, thus, more income accrues to people earning above the taxable maximum), the portion of American wages subject to the Social Security tax fell from 90 percent in 1983 to 81 percent in 2015, the CBO said that year: The CBO “expects this disparity in growth in earnings to continue for at least the next decade … to about 79 percent by 2025.”

And as the gap continues to widen, tax revenues for the Social Security program are falling. The CBO estimated in 2016 that Social Security revenues will be 4.4 percent of GDP in 2029; by 2090 they will be 4.3 percent. Yet Social Security payments — to keep up with an aging population — will cost 6.1 percent of GDP in 2029 and 6.4 percent by 2090.

Solutions

In a 2016 report, the Congressional Research Service — Congress’s in-house think tank — described a couple of options that lawmakers who want to reform Social Security can consider. The report urges haste: “If changes were made sooner, they could be smaller, since the burden of lower benefits or higher taxes would be shared by more beneficiaries or workers over a longer period.”

For starters, Congress could legislate a decrease in benefits (the decrease would happen by default after the trust fund runs out anyway). Second, it could save the scheduled benefits by introducing a 3.3 percent tax hike the year after the trust fund is depleted (2029 or 2034, depending on the model), and another 1.1 percent increase by 2090. Or, third, Congress could mandate a combination of tax increases and spending decreases to protect beneficiaries from a sudden loss of benefits. But that would not restore Social Security benefits to their current levels.

No matter what happens, the Congressional Research Service report points out, Congress will have to act because the law demands it: The Social Security Act requires payments be disbursed to eligible beneficiaries, yet other laws prohibit the spending of funds that are not available.

There are no easy fixes, notes the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a watchdog for government spending. But in early 2017, two members of Congress were working on two plans to tackle this fiscal crisis. Both Sam Johnson, a Republican from Texas, and John Larson, a Democrat from Connecticut, agree the Social Security program must be made solvent. Both would reduce benefits and increase taxes, but Larson’s plan would focus more on raising taxes, while Johnson’s would raise the retirement age and slow benefit growth for the wealthiest retirees.

Other research

Journalist’s Resource has profiled research questioning the Social Security Administration’s projections.

The Congressional Budget Office regularly updates its own projections. This CBO paper discusses reform options.

The Congressional Research Service offers some of the most detailed and readable analyses available on topics such as how benefits are taxed, the threat of insolvency, benefits to a deceased person’s family, federal appropriations, and a primer on Social Security.

Other resources

The Social Security Administration regularly circulates policy research and statistics on its beneficiaries, including by state and Congressional district.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget debunks Social Security myths. It also has a tool allowing users to calculate how much they stand to lose should the program go broke. For a man born in 1978, the Social Security Trust Fund would become insolvent when he is 56 years old, for example; if the program is not fixed, he stands to lose $119,333, on average, in lifetime benefits.

The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center discusses Social Security reform in its tax briefing book.