From highways to subways, power lines to the Internet, hospitals to firehouses, developed nations run on infrastructure. But as vital as all these infrastructure projects are, they’re also expensive, and once built, they require maintenance and, eventually, replacement. Yet with tight state budgets and difficult finances, maintenance is often deferred — sometimes with disastrous consequences — and mega-projects that once moved forward inexorably are often delayed or cancelled outright.

While bumping up property or sales taxes might once have been the way to go, voters have shown growing reluctance to support such increases. Fuel taxes, which traditionally fund road projects, have also fallen as people drive less, more workers telecommute, and legislatures hesitate to increase tax rates that have fallen in real terms.

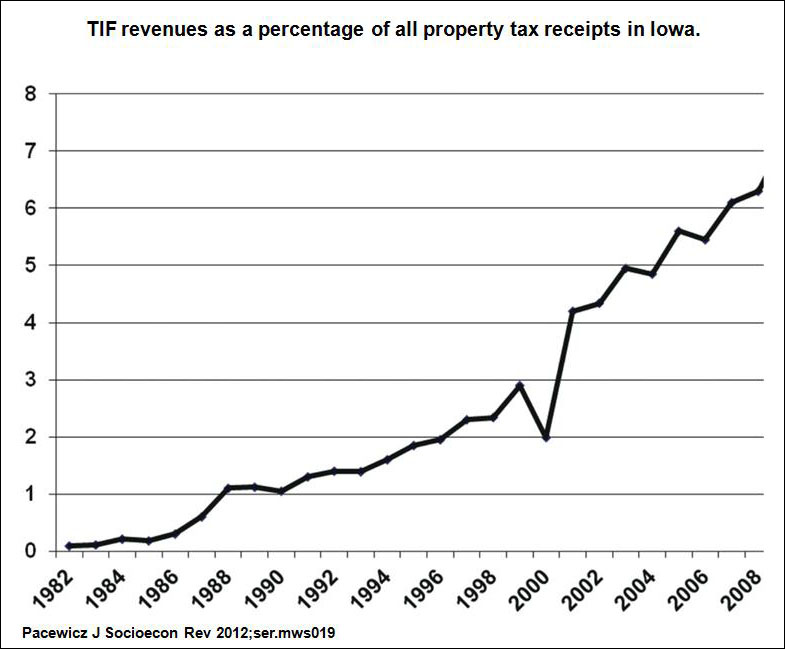

To move forward in such challenging fiscal and political times, more municipalities have been choosing to fund infrastructure projects through tax increment financing (TIF). It allows municipalities to sell bonds based on anticipated tax revenues that infrastructure improvements would enable. While TIF got its start in the 1950s, it’s coming into much greater prominence over the last two decades — such mechanisms are in place or have been discussed for projects such as riverfront development in Pittsburgh, a streetcar line in Arlington, Va., and a controversial pier in St. Petersburg, Fla.

The use of TIF has also grown at a time when municipalities and private entities are increasingly working together to build infrastructure projects. While cities once commonly built hospitals, housing or roads by themselves, now public-private partnerships are often formed, with risk and reward being spread between the municipal and private parties. Projects can be as small as a few units of public housing to billions of dollars of transit, education and park improvements.

The use of TIF has also grown at a time when municipalities and private entities are increasingly working together to build infrastructure projects. While cities once commonly built hospitals, housing or roads by themselves, now public-private partnerships are often formed, with risk and reward being spread between the municipal and private parties. Projects can be as small as a few units of public housing to billions of dollars of transit, education and park improvements.

A 2011 paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and the University of Michigan looked for patterns in the use of TIF and other tax-based business incentives. The authors found that governments representing poorer communities are more likely to offer business tax incentives; there was also a correlation found between the rate at which government officials are convicted of federal corruption and the probability that a community will offer direct tax reductions rather than tax increment financing.

A 2013 Brown University study published in Socio-Economic Review, “Tax Increment Financing, Economic Development Professionals and the Financialization of Urban Politics,” explores the funding method’s origins, use and implications. The author, Josh Pacewicz, lays out the history of TIF — it was originally a funding method of last resort for “blighted” neighborhoods — and looks at how it has evolved. He also examines the use of such financing in two Rust Belt cities in Iowa (anonymized as “River City” and “Prairieville” in the study) to better understand how it can influence municipal politics.

“Traditionally, cities have issued two types of bonds: general obligation and revenue bonds,” the author writes. “General obligation bonds are backed by a city’s property tax base and, because a city is legally obliged to repay them, are counted by rating agencies as debt. In contrast, revenue bonds are not backed by a city’s property tax base and therefore do not impact a city’s credit rating.” Because TIF-backed securities are based on future revenue, they receive more favorable ratings from credit agencies and weigh less heavily on cities. This fiscal advantage is just one of the factors that has encouraged their use.

The study’s findings include:

- In 1952 only a tiny fraction of U.S. states allowed tax-increment financing. By 2007 the proportion had grown to nearly 100% — 49 out of 50.

- “Cities in states where TIF has been used longer tend to be heavier users, although some southern cities (e.g. Houston) have adopted the practice within the past two decades and have quickly become very heavy users. Further, TIF spending tends to increase steadily once states have adopted statutes allowing the practice.”

- The percentage of urban land within TIF districts can be significant: In Iowa 10% of urban areas are so designated, as is 30% of the city of Chicago. “Several major California cities have designated over 50% of their land area as TIF districts.”

- “In the aggregate, overenthusiastic projections [on future tax receipts] are the norm, and TIF use is typically accompanied by large and mounting TIF debts. In 2009, for example, River City and Prairieville carried levels of TIF debt that were, respectively, equivalent to 3.5 and 1.7 times their annual property tax receipts. This means that both cities would need to divert all property taxes to servicing TIF debt for, respectively, 3.5 and 1.7 years to eliminate their debts.”

- In part because of its complexity, “TIF creates a structural opening for a new kind of urban actor who is capable of acting simultaneously as an insider and an outsider: a city representative not formally tied to the city.” Such development professionals play “dual roles of stewards of municipal finance and central leaders within development initiatives.”

- Because developers’ reputations depend on successful outcomes, “they become invested in these solutions, which are frequently expensive. To the degree that development professionals see such projects as vital, they are locked in to using TIF, because TIF … is frequently the least-bad financing option.”

- Politicians in River City and Prairieville expressed concern that TIF was “corporate welfare,” that it produces unsustainable debt, and that repaying it diverted crucial resources. “Despite such reservations, however, city council always unanimously approved TIF packages during my fieldwork,” the researcher states.

- Frequently, “politicians and other urban leaders who hire development professionals do not understand TIF’s mechanics and are unable to directly evaluate the technical virtuosity of development professionals.” And because such professionals can elevate their professional cache with large and visible projects, they have an even greater incentive to use TIF.

- “The desire to find creative solutions also leads development professionals to develop new TIF-like instruments. In many states, for example, cities have begun to securitize projected sales tax receipts and create structured bonds backed by this revenue stream in addition to projected increases in property taxes.”

“The special status of development professionals in urban politics has co-evolved with a set of professional incentives that do not align with the city’s long-term fiscal outlook,” the author concludes. “First, they have an incentive to fund large development initiatives, which can allow them to move to a more prestigious position in another city before the long-term fiscal consequences materialize. Second, they have come to identify their professional identity with the capacity to creatively solve any problem, and this gives them an incentive to create ever-more elaborate, and generous, financing schemes with TIF.”

Releated research: A 2013 report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “Regenerating America’s Legacy Cities,” examines the challenges and opportunities 18 U.S. metropolitan areas facing manufacturing decline and population loss. The authors, Alan Mallach and Lavea Brachman, advocate step-by-step “strategic incrementalism” as a path to economic development, rather than the silver-bullet approach of signature architecture, a sports stadium or other megaprojects. Also of interest is “Economic Distress and Resurgence in U.S. Central Cities: Concepts, Causes and Policy Levers,” a literature review by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston on U.S. central city growth and distress from 1950 to 2000.

Keywords: infrastructure, California, municipal, corruption