Fall is in the air again, and so is the threat of a government shutdown. Picking up from earlier this year, the Obama administration and a divided Congress continue to struggle through yet another round of budget negotiations. The White House is in favor of revoking the across-the-board spending cuts put in place last March — collectively referred to as sequestration — and replacing them with a combination of other reductions and increased taxes. House Republicans would prefer additional budget cuts, and the Affordable Care Act and renewable-energy programs are in their bulls-eye.

In a September 15 interview, President Obama linked the Republican push for even deeper budget cuts to rising income inequality across the country. “There’s no serious economist out there that would suggest that, if you took the Republican agenda of slashing education further, slashing Medicare further, slashing research and development further, slashing investments in infrastructure further, that that would reverse some of these trends of inequality,” he said. Of course, President Obama and Congress — including 85 House Republicans — already agreed to a tax hike on the wealthy as part of the “fiscal cliff” deal, raising the top marginal tax rates from 35% to 39.6% and increasing tax rates on capital gains. Because of this, the White House has claimed it has forged the “most progressive income tax code in decades.”

As the United States slowly recovered from the 2007-2009 “Great Recession,” rising income inequality permeated policy debates and began to make headlines. Some in the news media have even suggested that inequality itself is a primary cause driving political dysfunction — bringing about a kind of vicious circle. Census Bureau statistics released in September 2013 suggest, to many, a kind of stagnation — and a “sinking” middle class.

But might the recent progressive tax changes reverse the overall patterns? What is the early evidence, and how might the situation be turned around?

A comprehensive update from Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez suggests the tax changes may not be enough in the long run to reverse widening inequality. His new paper, “Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” builds upon earlier research Saez conducted with Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics. (Their work remains a leading source and barometer on these issues for the media and academia.) In the updated research, Saez indicates that the wealthiest 1% of earners are close to making a full recovery from the recession while bottom 99% have barely recovered at all. Placing this in a historical context, Saez explains that inequality has been growing in the U.S. labor market over the last 30 years, with the top earners capturing an ever-increasing portion of productivity gains. He points to a number of factors to explain this, highlighting in particular “the retreat of institutions developed during the New Deal and World War II — such as progressive tax policies, powerful unions, corporate provision of health and retirement benefits, and changing social norms regarding pay inequality.”

Key findings of the study include:

- From 2007 to 2009, average family income declined by 17.4%, the largest two-year drop since the Great Depression.

- Average real income for the top 1% of earners fell 36.3% while average real income for the bottom 99% fell by 11.6%. By comparison, the top 1% absorbed a larger fraction of losses in the 2000-2002 recession (57%) than in the Great Recession (49%).

- From 2009 to 2012, average income per family grew by 6%, but these gains were very unevenly distributed. “Top 1% incomes grew by 31.4% while bottom 99% incomes grew only by 0.4% from 2009 to 2012. Hence, the top 1% captured 95% of the income gains in the first three years of the recovery.”

- Average real incomes of the bottom 99% grew by 6.6% from 1993 to 2012, an annual growth rate of 0.34%. The top 1% of incomes grew by 86.1% during the same period, an annual growth rate of 3.3%.

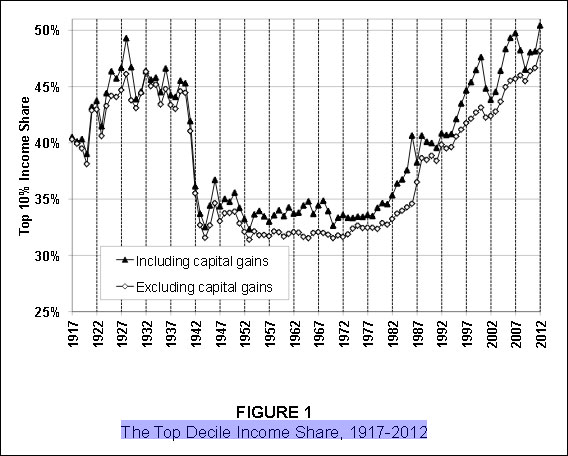

- “The top decile income share in 2012 is equal to 50.4%, the highest ever since 1917.” This level “even surpasses 1928, the peak of stock market bubble in the ‘roaring’ 1920s.”

Such results should not come as a surprise given historical patterns, Saez states: “Falls in income concentration due to economic downturns are temporary unless drastic regulation and tax policy changes are implemented and prevent income concentration from bouncing back.” The larger-scale policy changes after the Great Depression as part of the New Deal were effective, he suggests, reducing income inequality until the 1970s. In contrast, “the policy changes that took place coming out of the Great Recession (financial regulation and top tax rate increase in 2013) are not negligible but they are modest relative to the policy changes that took place coming out of the Great Depression.”

The following chart comes courtesy of Saez’s study:

Related research: In a 2013 Pew Research Center report on income growth from 2009 to 2011, authors Richard Fry and Paul Taylor describe the recovery as very uneven: “The upper 7% of households saw their aggregate share of the nation’s overall household wealth pie rise to 63% in 2011, up from 56% in 2009.” The net worth of households in the upper 7% of the wealth distribution also rose, on average, by an estimated 28%, while households in the remaining 93% actually saw their net worth drop by 4%. A 2013 study from New York University was even more bleak: It found that between 2007 and 2010, overall median wealth in America (assets less debts) fell a “staggering” 47%.

A 2013 study published in Perspectives on Politics, “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” finds that there would be little support among the wealthiest Americans for policy reform aimed at reducing income inequality. The scholars — Benjamin I. Page and Jason Seawright of Northwestern University, and Larry M. Bartels of Vanderbilt University — indicate that although the wealthy are aware of inequality, “by large margins they opposed governmental redistribution of income or wealth” and “in every one of the five specific cases for which we have comparable data, the general public leaned more toward increased regulation than the wealthy did.” Furthermore, the wealthy are more likely be highly active in politics, “far more so than the typical citizen,” which could affect the likelihood of passing increasingly strict regulation reforms. These preferences stand in stark contrast to the policy preferences of the majority of Americans, according to research from Harvard Business School and Duke University.

For a sense of the recent media reporting in this area, see in-depth features by Reuters and GlobalPost.

Tags: financial crisis