While high-level speculation continues on the future of news and information, research studies are providing a more under-the-hood look at the practices of journalists, outlets, and the digital networks in which they operate. Here’s a recent sampling from the world of academic journals and conferences.

For a look at the bleeding edge of ideas, also check out new research papers on using “crowd workers” to generate encryption keys and the social costs of “friendsourcing” questions and information.

(Note: This article was first published at Nieman Journalism Lab.)

_______

“Rumor Cascades”

Facebook and Stanford University, prepared for the 2014 International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. By Adrien Friggeri, Lada A. Adamic, Dean Eckles and Justin Cheng.

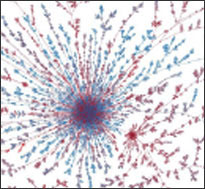

The researchers start by identifying known rumors through Snopes.com (the urban legend reference site); they analyze how nearly 4,800 distinct rumors circulated on Facebook. Among the rumors studied, 22% were related to politics and 12% involved fake or doctored images. It appears that false rumors thrive on Facebook: In the entire Snopes database of rumors, 45% are flat-out false, while 26% turned out to be true; in contrast, 62% of rumors on Facebook are false and only 9% prove to be true. Interestingly, the authors note, “true rumors are more viral — in the sense that they result in larger cascades — achieving on average 163 shares per upload whereas false rumors only have an average of 108 shares per upload.” Some rumors are shared hundreds of thousands of times. Even when people discover the falsity of a rumor and delete their reshare, it does not appear to affect the unfolding cascade.

Friggeri, Adamic, Eckles and Cheng note the fast-moving, highly sudden nature of these information cascades. The “popularity of rumors — even ones that have been circulating for years in various media such as email and online social networks — tends to be highly bursty. A rumor will lie dormant for weeks or months, and then either spontaneously or through an external jolt will become popular again. Sometimes the rumors die down on their own.” The paper does not propose a mechanism to explain these sudden “mystery” flare-ups, however. “It would be interesting,” the researchers conclude, “to examine whether rumor flare-ups are fueled by the presence of individuals who have never been exposed to the rumor, or whether, to the contrary, the rumor relies on those who know it well to retell it when prompted.”

“Coproduction or Cohabitation: Are Anonymous Online Comments on Newspaper Websites Shaping Content?”

Western Washington University, published in New Media & Society. By Carol E. Nielsen.

Based on a substantial national survey of 583 journalists conducted in 2010, Nielsen explores how media members feel about anonymous comments on their articles, and whether or not they find them useful. The data show that “35.8% of journalists reported that they ‘frequently’ or ‘always’ read comments on their own work, 29% reported they ‘sometimes’ read comments on their work, and 35.2% reported that they ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ read comments on their work.” About three-quarters of journalists surveyed said that online comments should not be anonymous. Nielsen quotes one reporter who gave some qualitative feedback: “Those who post are free to lie and vent without accountability. The result is that online comments sabotage the credibility and dignity of the entire news organization.”

Just under half of respondents (45%) “slightly or strongly agreed” that they should not respond to online comments, though three-quarters agreed they should respond to set the record straight with regard to factual inaccuracies. Most journalists surveyed said it was not because of a lack of time that they forego reading comments, rather it’s because they don’t think it’s worth it. “While 53.5% of journalists responded that comments sometimes showed them a new perspective, only 8.4% said that frequently or always happened and 38.1% said that rarely or never happened.” Comment forums are for readers, as far as most journalists are concerned. “This study,” Nielsen writes, “concludes that journalists have viewed readers not as coproducers, but rather as users cohabiting the platform.”

“Customer Orientation on Online Newspaper Business Models with Paid Content Strategies”

Carlos III University of Madrid and the University of Texas, published in First Monday. By Manuel Goyanes and George Sylvie.

The study sets out to examine how news organizations measure customer satisfaction and respond to preferences with their paid content strategies — “paywall, metered model, freemium or the various sorts of virtual kiosks.” Goyanes and Sylvie analyze Britain’s The Times and the Financial Times, as well as Spain’s El Mundo. They base their conclusions mostly on 2012 interviews with digital, marketing and sales representatives at the news outlets and available internal documents.

How aggressive are these organizations in responding to the wants and needs of customers, and what factors seem to influence their strategies? The Financial Times boasts a data analysis team of 25 — five in London and 20 in Manila, allowing the outlet to begin to “differentiate content over different devices and time slots.” Meanwhile, the Times allows comments on the platform only from registered users, “avoiding ‘information noise’” in terms of user feedback. Customers now get “more personalized attention” than ever. At each outlet, there are “intense processes of innovation, experimentation and testing of new business and product campaigns and practices.” The case studies show an “enhanced effort to develop and have online tools — e.g., registration, comment feedback and social media — to supplement the traditional vehicles of market studies, reader panels, etc., and deliver additional, analyzable reader data.” The authors conclude, however, that “despite the strategic planning of media groups employing paid content strategies, the economic uncertainties and discrepancies on their adoption indicate that charging for content remains an option of an experimental nature,” and other revenue streams, such as print editions, remain crucial to supporting the business.

“Embedding Content from Syrian Citizen Journalists: The Rise of the Collaborative News Clip”

California State University and UCLA, published in Journalism. By Melissa Wall and Sahar El Zahed.

Analyzing the way that the New York Times’ “The Lede” live blog incorporates Syrian citizen journalistic video, Wall and El Zahed coin the term “collaborative news clip” to describe the joint gatekeeping and shared framing news process that takes place. They examine 82 blog posts from 2012, which used a total of 162 citizen videos. Citizen videos were more often labeled a “clip,” as opposed to professional videos, which were frequently called a “report.” Only 14 were in English, or had subtitles or a mix of Arabic-English. Most have no beginning-middle-end structure; they have an “in-the-middle” of the story structure.

“Productive usage of the Syrian citizen videos requires context and place specific knowledge,” Wall and El Zahed conclude, “a level of understanding that The Lede achieves in part by turning to insiders, activists within the conflict, to help with their selection and explanations. In this way, The Lede provides a means for Syria’s citizen journalists and their supporters to have a louder voice on the Web pages of a major world news outlet. In the process, some narrative power may be shifting to a tier of citizen-activists who create and/or identify local content.”

“A Digital Juggling Act: New Media’s Impact on the Responsibilities of Local”

Ithaca College, published in Electronic News. By Anthony C. Adornato.

This case study assesses how work flow issues play out for TV journalists who now must do much more than just stand-up reporting before an on-scene camera. Based on in-depth interviews with eight television journalists of varying levels of experience who operate in a medium-sized Northeast media market, Adornato offers granular detail on reporters’ experiences. The reporters generally felt that social media was useful for newsgathering. However, “Reporters were increasingly being asked to verify information that people were posting online; sometimes, this meant they were spending valuable time investigating rumors.” Daily responsibilities generally increased because of the pace of social media: “Reporters did not — and could not — wait for the 5 p.m., 6 p.m. or 11 p.m. broadcasts to deliver information about stories,” he notes. “Reporters recognized the audience expects information in real-time and across multiple online platforms.”

Adornato reveals other challenges that are likely common to many local television reporters.“Reporters found the process of getting information to the Web team and others involved in the traditional news broadcasts cumbersome,” he writes. “Because of the lack of coherent internal communications, reporters often had to carve out critical time to relay information to different coworkers — Web staff member, producer and assignment editor.” The TV reporters also found themselves “hard pressed to relinquish control of the story to the Web team. Instead, they spent a significant amount of time editing the Web version of their stories.” On the whole, the journalists interviewed said they believed social media channels brought them closer to viewers; their “ongoing interactions build a level of trust and credibility with the audience.”

“Twilight or New Dawn of Journalism?”

The Reuters Institute, University of Oxford, published in Digital Journalism. By Robert G. Picard.

Picard, a media economics and policy expert, furnishes a high-level overview of the industry changes at hand. He emphasizes that the “practices of journalism are shifting from a relatively closed system of news creation — dominated by official sources and professional journalists,” and that this is “not undesirable because it means that fewer institutional elites are deciding what gets attention and how it is framed than in the past.” However, he also warns that newer media institutions are “able to skew the availability of news and information through search, aggregation and digital distribution infrastructures. These are creating new mechanisms of power and a new class of elites influencing content.”

In terms of changes for the business model, Picard puts recent shifts in historical perspective: “What is clear is that news providers are becoming less dependent on any one form of funding than they have been for about 150 years.” This is also potentially a welcome change, as it reduces the “influence of commercial advertisers that significantly influenced the form, range and practices of news provision in the 20th century.” Still, we cannot take quality news for granted. “We are experiencing neither an end nor a new dawn of journalism; we are experiencing both,” Picard concludes. “The historical, social and economic contexts of the changes occurring in journalism indicate we are in a transition not a demise of journalism.”

Further reading: For a look at the impact of native advertising on the perceived credibility of a site, see “Native Advertising and Digital Natives: The Effects of Age and Advertisement Format on News Website Credibility Judgments,” published in the journal of the International Symposium of Online Journalism (see Nieman Lab summary here.) The study suggests that the presence of native advertising has “no significant effect on the viewer’s perception of credibility.”