In recent years, an increasingly bipartisan consensus around prison reform has begun to take shape, uniting policymakers in Congress who are typically on opposite sides of law-and-order issues. At the same time, nationally publicized events relating to the treatment of young black men by the criminal justice system have brought urgency to the issue, while corresponding new levels of focus from social media and news outlets — and the appearance of new reporting initiatives such as The Marshall Project — have helped drive the policy discussion.

Reporters writing about incarceration rates and the complexities of the sentencing laws and prison systems are frequently confronted with a slew of facts and figures, some of which can seem contradictory and fraught with political controversy. It therefore can be difficult to discern the most important and authoritative findings that speak to the current moment in the United States.

A landmark 2014 report, “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences,” from the National Research Council of the National Academies — the preeminent research body in the United States, part of the National Academy of Sciences and chartered by Congress — was authored by a committee of leading criminal justice scholars from across the country. The project’s chair and vice chair were Jeremy Travis of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at City University of New York and Bruce Western of the Department of Sociology and Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

The report’s findings and insights can credibly and authoritatively anchor coverage and debate about this issue. The following are key statements within the 464-page document.

Empirical findings:

- In 2012 the U.S. penal population was 2.23 million adults, the largest in the world, with an incarceration rate of 707 per 100,000. That year, nearly 25% of the world’s prisoners were held in American prisons, yet the United States constituted just 4.5% of the global population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

- “During the 1980s, the U.S. Congress and most state legislatures enacted laws mandating lengthy prison sentences — often of 5, 10, and 20 years or longer — for drug offenses, violent offenses, and ‘career criminals.’ In the 1990s, Congress and more than one-half of the states enacted ‘three strikes and you’re out’ laws that mandated minimum sentences of 25 years or longer for affected offenders. A majority of states enacted ‘truth-in-sentencing’ laws requiring affected offenders to serve at least 85% of their nominal prison sentences.”

- “From 1980 to 2000, the number of children with incarcerated fathers increased from about 350,000 to 2.1 million — about 3% of all U.S. children. From 1991 to 2007, the number of children with a father or mother in prison increased 77% and 131%, respectively.”

- “Among white male high school dropouts born in the late 1970s, about one-third are estimated to have served time in prison by their mid-30s. Yet incarceration rates have reached even higher levels among young black men with little schooling: among black male high school dropouts, about two-thirds have a prison record by that same age — more than twice the rate for their white counterparts. The pervasiveness of imprisonment among men with very little schooling is historically unprecedented, emerging only in the past two decades.”

Conclusions based on the scientific evidence:

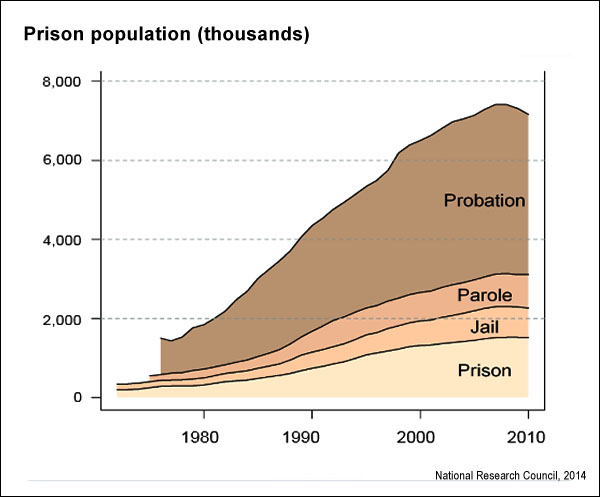

- “The growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique.”

- “The unprecedented rise in incarceration rates can be attributed to an increasingly punitive political climate surrounding criminal justice policy formed in a period of rising crime and rapid social change. This provided the context for a series of policy choices — across all branches and levels of government — that significantly increased sentence lengths, required prison time for minor offenses, and intensified punishment for drug crimes.”

- “The incremental deterrent effect of increases in lengthy prison sentences is modest at best. Because recidivism rates decline markedly with age, lengthy prison sentences, unless they specifically target very high-rate or extremely dangerous offenders, are an inefficient approach to preventing crime by incapacitation.”

- “People who live in poor and minority communities have always had substantially higher rates of incarceration than other groups. As a consequence, the effects of harsh penal policies in the past 40 years have fallen most heavily on blacks and Hispanics, especially the poorest.”

The report’s authors provide many recommendations, chief among them: “Given the small crime prevention effects of long prison sentences and the possibly high financial, social, and human costs of incarceration, federal and state policy makers should revise current criminal justice policies to significantly reduce the rate of incarceration in the United States. In particular, they should reexamine policies regarding mandatory prison sentences and long sentences. Policy makers should also take steps to improve the experience of incarcerated men and women and reduce unnecessary harm to their families and their communities.”

An accompanying video with the report also presents top-level findings:

Keywords: prisons, African-American, minorities, drug crimes, high school drop out, incarcerated fathers, mandatory minimum, marijuana, truth in sentencing