Fifty years after Peggy Lee sang about a woman’s ability to both bring home the bacon and fry it up in a pan, working women still struggle to balance the competing demands of work and home. Women now have higher rates of university attendance than men, represent nearly 60% of the U.S. workforce and now can even serve in combat roles in the U.S. military. Despite these changes, equality remains elusive.

The issue of work/life balance has recently generated an extended discussion in the news media, initially prompted by Princeton professor and former State Department official Anne-Marie Slaughter’s August 2012 essay in The Atlantic, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.” Responses strongly supported or dismissed her concerns. Slaughter’s former boss, Hillary Clinton, articulated her own distinctive perspective. At the same time, the political world has its own gender-gap dynamics.

A woman’s ability to climb the corporate ladder and to earn wages on par with male counterparts along the way is still a work in progress. Women earn as little as 77 cents for every dollar that men do, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Although there are different interpretations of this “pay gap” (slightly varying numbers are sometimes cited), there is nevertheless general empirical evidence that gender wage discrimination continues across all segments of the American economy. Even when they make it to the corner office, women’s compensation doesn’t match that of male executives. Women still have relatively few seats on corporate boards — just 14% in recent years — and ran about a dozen of the Fortune 500 companies as of 2010.

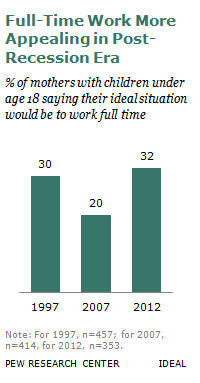

According to the Pew Research Center, 20% of mothers with children in 2007 said their ideal life situation involved full-time work; but by 2012, that figure was 32%, likely the result of the economic recession.

According to the Pew Research Center, 20% of mothers with children in 2007 said their ideal life situation involved full-time work; but by 2012, that figure was 32%, likely the result of the economic recession.

Some academic research continues to focus on structural barriers, while other scholarship has shifted to examining possible solutions. One possible way to address the pay gap is empowering more women to bargain for higher salaries. It’s an issue that has received substantial attention in the academic world, but the empirical findings suggest that gender itself is not always a consistent predictor of negotiating behavior. As Harvard Kennedy School scholars Hannah Riley Bowles and Iris Bohnet write in a special issue of Negotiation Journal, “what recent research has shown is that gender effects on negotiation are contingent on situational factors that make gender more or less relevant, salient, and influential.”

Gender issues in the workplace also play out in subtle and often overlooked ways. As Deborah Tannen of Georgetown has noted, women tend to be interrupted more often than men, and these dynamics play out across meetings and boardrooms. Women are also less likely to be plugged into robust professional networks, which can stymie budding female scientists and experienced administrators alike. It may also be that networking strategies that have proven effective for male leaders may not be as useful for women.

Successful female professionals can often come across as out of touch with the typical working woman with respect to work/life balance. A provocative front-page article in the New York Times took a critical look at Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s new book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, and the accompanying publicity campaign, generating wide-ranging responses. (For more perspective, see this article in The Daily Beast; and see Slaughter’s review of Sandberg’s book in the New York Times.) In February 2013, Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer announced the end of telecommuting for its employees as of June 2013. Mayer herself returned to work two weeks after giving birth. Some business analysts and former company employees applauded the decision, but others are less sanguine. One Yahoo worker, quoted in Kara Swisher’s “All Things D” blog from the Wall Street Journal, said, “When a working mother is standing behind this, you know we are a long way from a culture that will honor the thankless sacrifices that women too often make.”

Caring for others remains primarily a female responsibility. While the percentage of women in the workforce has risen from 43.3% in 1970 to 58.6% in 2010, women continue to also work as the primary caretakers of children, ill or disabled family members or aging parents. According to a 2009 report from the National Alliance for Caregiving, between 59% and 75% of those caring for at least one ill or disabled relative are women. Nearly two out of three family caregivers are employed outside the home and nearly half live in households earning less than $44,100 (twice the federal poverty level for a family of four in 2009.) Research shows that couples who didn’t fit the perceived norm of a male breadwinner and the female caretaker were judged harshly.

Caring for others remains primarily a female responsibility. While the percentage of women in the workforce has risen from 43.3% in 1970 to 58.6% in 2010, women continue to also work as the primary caretakers of children, ill or disabled family members or aging parents. According to a 2009 report from the National Alliance for Caregiving, between 59% and 75% of those caring for at least one ill or disabled relative are women. Nearly two out of three family caregivers are employed outside the home and nearly half live in households earning less than $44,100 (twice the federal poverty level for a family of four in 2009.) Research shows that couples who didn’t fit the perceived norm of a male breadwinner and the female caretaker were judged harshly.

Researchers at the Center for Gender Research in the Professions at University of California-San Diego just released a report in March 2013 debunking the conventional wisdom that women are outpacing men in the workplace. The report, “The Persistence of Male Power and Prestige in the Professions: Report on the Professions of Law, Medicine, and Science & Engineering,” found that even professional women in prestigious positions lag behind men, who still wield considerable clout in the office. Women, however, continue to be well-represented in the lower ranks of the service industry. Further, a 2011 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, “Evidence That Gendered Wording in Job Advertisements Exists and Sustains Gender Inequality,” demonstrated that study participants responded to the language in job postings differently depending on their gender. The researchers, citing the “social dominance theory,” suggest that such responses can be used to discourage women to enter male-dominant occupations, and vice versa.

A 2013 conference at Harvard Business School produced more than a dozen open-access working papers and research essays based around the theme of “Gender and Work: Challenging Conventional Wisdom.”

Below are reports and studies that provide further perspective on women negotiating the culture of work and balancing work and home responsibilities. A larger library of some 30 useful background studies is also curated here.

—————————–

“State Policies and Gender Earnings Inequality: A Multilevel Analysis of 50 U.S. States Based on U.S. Census 2000 Data”

Ryu, Kirak. The Sociological Quarterly, Spring 2010, Vol. 51, No. 2. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01170.x.

Findings: The more progressive a state’s institutional environment, the smaller the gender gap in earnings. The pay gap for women workers in states with large public social-service sectors is larger than that for those in states with small public social-service sectors. Women working in progressive state institutional environments are “more likely to be employed in managerial occupations and less likely to be channeled into female-typed occupations.” “State governments usually provide jobs for social services such as health, welfare and education, and these positions attract more female employees than male employees. However, the consequences of these employment patterns are not beneficial for female employees in that occupations in these sectors pay less than do other sectors of the labor market.” Whether or not more women are hired in managerial positions does not appear dependent on environments where earnings are more equal generally. In other words, the “net odds of females employed in managerial occupations is not significantly associated with the gender gap in earnings.”

“Family Change and Time Allocation in American Families”

Bianchi, Suzanne M. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, November 2011, Vol. 638, No.1. doi: 10.1177/0002716211413731.

Findings: “As market work increased, mothers’ time in childcare activities declined from 10 to 8.5 hours per week between 1965 and 1975, but then increased. After 1985, primary childcare time of mothers rose to almost 12.6 hours per week by 2000 and has fluctuated around 14 hours per week during the 2003 to 2008 period.” In addition, “fathers have increased the time they spend on childcare over the past two or three decades. For fathers, more childcare hours were added to long work hours, especially for married fathers who average more than 40 hours of paid work per week (regardless of the age of their children).” Evidence supports the theory that, currently, middle class parents engage in intensive parenting. This means that now, more than ever, parents and involved in several extracurricular activities with their children. Despite the higher weekly average of child-care time, parents still report having “too little time with their children,” and even for unemployed mothers, 18% report not having enough time with their children.

“Women’s Well-Being: Ranking America’s Top 25 Metro Areas”

Guyer, Patrick Nolan; Bennett, Neil; Brindisi, Alicia; Kennedy, Kevin; Tung, Diana. Measure of America, Social Science Research Council, 2012.

Findings: The top-scoring metropolitan areas were Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Boston, Minneapolis-St. Paul and New York; the lowest scores were Riverside-San Bernardino, San Antonio, Houston, Tampa-St. Petersburg and Pittsburgh. Women in Washington, D.C. ($37,657), San Francisco ($35,380) and Boston ($31,503) earned significantly more annually than their counterparts in Riverside-San Bernardino ($22,306), Pittsburgh ($23,557) and San Antonio ($24,961). The 2012 poverty guideline for a family of four in the continental United States is $23,050. Women tended to earn more in areas where a higher percentage of women were unmarried. Educational attainment and enrollment accounts for much of the differences in wages. Close to 20% of women in Washington, D.C., hold an advanced degree compared to only 6.9% of those in San Bernardino. Educational attainment and enrollment accounts for much of the differences in wages. Nearly 20% of women in Washington, D.C., hold an advanced degree compared to only 6.9% of those in San Bernardino. “In Pittsburgh, Boston and Minneapolis-St. Paul, only about 6% of young women ages 25 to 34 did not complete high school, the best outcome on this indicator among the 25 cities. In contrast, in Riverside-San Bernardino, Los Angeles and Houston, that rate is almost 17%, nearly three times the rate among the top three.”

“Money, Benefits and Power: A Test of the Glass Ceiling and Glass Escalator Hypotheses”

Smith, Ryan A. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, January 2012, Vol. 639, No. 1. doi: 10.1177/0002716211422038.

Findings: Contrary to the “glass ceiling” theory, the overall wage gap is not primarily caused by the gender difference at the top levels; instead, “the relative white male advantage remains the same at each level of authority for each ethnoracial and gender group.” Examining the patterns of promotion reveals some evidence supporting both theories: “White male supervisors and managers are paid better under dissimilar superiors than under white male superiors; the opposite is true for all other groups [and] the wage gaps between white men and other groups increase from supervisory to managerial authority, and the wage gaps are wider between white men and other groups in work settings where employees report to women and minorities.” The advantage for white males is not only in wages and promotions but also in employee benefits: “White men are more likely than any other group to have sick leave, individual health insurance, family health insurance and retirement plans.”

“Gender Reversal on Career Aspirations”

Patten, Eileen; Parker, Kim. Pew Research, April 2012.

Findings: “The percentage of young women (ages 18-34) who reported that career success is ‘one of the most important things’ or ‘very important’ to them rose 10 percentage points in 14 years, from 56% in 1997 to 66% in 2010/2011. The number of young women who said a high-paying career is ‘one of the most important things’ or ‘very important’ has also risen, from 59% in 1997 to 66% in 2010/2011…. While the median age for motherhood rose by two years (from 22 in 1960 to 24 in 2010/2011), the median age for marriage increased by seven years (from 20 in 1960 to 27 in 2010/2011) during the same period. More than 70% of women with children worked in 2010/2011, up 24 percentage points since 1975. Women with younger children (under age 6) participated in the labor force slightly less (64%) than those with older children (77%). In 2010/2011, 44% of women ages 18 to 24 were enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs and 36% of women in this age group had already earned a bachelor’s degree. Of men the same age, 38% were attending college classes and 28% had bachelor’s degrees. Despite relatively high rates of educational attainment and labor force participation, women still faced unequal earnings compared to their male colleagues. In 2010, a woman’s median weekly wage was $669 and a man’s was $824. A woman earned 62% of her male counterpart’s salary in 1979 and 80% to 81% of his pay in 2010/2011. Younger age groups recorded lower levels of wage disparities, however, than those between 35 and 64.”

“Balancing Work and Family After Childbirth: A Longitudinal Analysis”

Grice, M.M.; McGovern, P.M.; Alexander, B.H.; Ukestad, L.; Hellerstedt, W. Womens Health Issues, January-February 2011, Vol. 21, No. 1. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.003.

Findings: By 11 weeks after childbirth, 53% of the women returned to work; by six months, almost all the women were back at work (all in the survey sample had worked in the year preceding childbirth.) Women experienced job spillover into the home more frequently than home spillover into work…. There was “a positive relationship between health and total hours worked, with each additional hour of work being associated with a slight increase in both mental and physical health.” A positive association was found between women’s mental health scores and both social support from co-workers and positive feedback from family members about the way a woman “balanced both work and family.” There was an inverse relationship between work flexibility and job spillover, with more flexible work arrangements not increasing the amount of time a woman is able to spend with her child. Longer periods of work leave for childbirth were associated with a longer duration of breastfeeding.

“Women in the Labor Force: A Databook”

U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2011. Report 1034.

Findings: The percentage of women in the workforce has risen from 43.3% in 1970 to 58.6% in 2010. Over the same period, the percentage of men in the workforce fell from 79.7% to 71.2%. The median weekly earnings for a woman working full-time in 2010 was $669, 81% of a man’s median weekly earnings ($824). In 2010 a woman age 25 or older with a bachelor’s degree or higher earned a median weekly salary of $986; a woman with an associate’s degree earned $677 per week and one with a high school education earned $543 per week. For more than half of couples (55%), both husbands and wives worked in 2009, up from 44% in 1967. In 2009, working wives earned 37% of their families’ incomes, a 10 percentage-point increase from 1970. “The proportion of wives earning more than their husbands also has grown. In 1987, 18% of working wives whose husbands also worked earned more than their spouses; in 2009, the proportion was 29%.” More women (7.5%) than men (6.6%) make up the ranks of the working poor. “Black and Hispanic women were significantly more likely than their White or Asian counterparts to be among the working poor. Poverty rates for Black and Hispanic working women were 14.2% and 13.6%, respectively, compared with 6.4% and 5.5%, respectively, for White and Asian women.” While the percentage of self-employed women in 2010 (5.2%) was less than that of their male counterparts (7.6%), the number of self-employed women has nearly doubled — from 35,027,000 to 65,164,000 — between 1976 and 2010.

“The Gender Gap in Executive Compensation: The Role of Female Directors and Chief Executive Officers”

Shin, Taekjin. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, January 2012, Vol. 639, No. 1. doi: 10.1177/0002716211421119.

Findings: Having a greater proportion of women on compensation committees was found to reduce inequality in salaries paid to women compared to their male counterparts. This increase in the representation of women was not correlated with any adverse impact on salaries paid to male executives. Firms with one woman on the compensation board saw average total compensation (including annual salary, bonuses, stock options, and other long-term incentive pay) for women increase by $302,000, a 34% increase. Adding another woman to the compensation committee was correlated with yet another 38% jump in salaries for women, to an overall average of $1,635,000. Firms with at least two women on compensation committees (which is usually comprised of four members) removed salary disparities altogether. An overwhelming 81% of the firms in the sample had no female representation in their compensation committees, while only 10% of the firms had equal gender representation in compensation committees. Among top positions, females were more likely to hold lower-ranking positions of EVP (executive vice president), SVP (senior vice president), counsel and secretary, while males usually took the positions of CEO (chief executive officer), COO (chief operating officer), president and chair.

“Women in the Federal Government: Ambitions and Achievements”

Grundmann, Susan Tsui. U.S. Merit Systems Production Board, May 2011.

Findings: Women still only account for roughly 30% of the Senior Executive Service. Part of this might be due to lower willingness to relocate among female employees and the fact that “approximately 72% of positions in the career Senior Executive Service are located in the greater Washington, D.C., metropolitan area.” Differences in pay have been reduced across the board. These “gains have been greatest in administrative occupations, where the median salary for women is now almost 93% of that for men, up from just over 83% in 1991.” The difference between genders in the average years of service of employees in professional and administrative occupations has decreased by nearly five percentage points in professional positions; the difference has become inverse in administrative positions, with women having more years of work experience than their male counterparts on average. Part of these shifts can be explained by the fact that “in the United States, women now account for a majority of college students and a majority of the college degrees conferred each year”…. Even though women are equally as likely as men to hold the necessary qualifications for external hiring, “women are still somewhat more likely to be hired when an agency fills a position through internal hiring instead of external hiring, or fills a position at entry-level or mid-level instead of upper-level.”

“Can an Agentic Black Woman Get Ahead? The Impact of Race and Interpersonal Dominance on Perceptions of Female Leaders”

Livingston, Robert W.; Rosette, Ashleigh Shelby; Washington, Ella F. Psychological Science, March 14, 2012. doi: 10.1177/0956797611428079.

Findings: Race was found to be a significant factor when evaluating assertiveness in women: White women received more negative evaluations when they expressed dominance compared to black women. “Black women tend to be defined as nonprototypical, marginal members of both their racial and gender groups, and consequently are often rendered ‘invisible’…. As an ironic consequence of this invisibility, black women may be buffered from many of the racial hostilities directed toward black males.” An individual’s race was not a factor when evaluating stereotypical feminine behavior: “There was no difference between evaluations of black and white women when they expressed communality.” Assertiveness among men was also rated differently according to race: “Black men were penalized for expressing dominance…. However, White men were not penalized.”

“Sexism and Gender Inequality Across 57 Societies”

Brandt, Marc J. Psychological Science, November 2011, Vol. 22, No. 11. doi: 10.1177/0956797611420445.

Findings: Even after controlling for changes in society over time, and for differences between as well as within societies, the data suggest that “greater sexism predicts decreases in gender equality over time.” Separating and tracking the effects of men’s and women’s expressions of mainstream sexist ideologies shows that “sexism may be a consensual legitimizing myth endorsed by both high-status and low-status groups in the creation of gender hierarchy.” The researchers found that “sexism is more prevalent in countries that are less developed and have more gender inequality.” Overall, the “results presented here suggest that sexism not only legitimizes gender inequality, but actively makes it worse.” This means that while employment decisions, pay inequity and violence against women are all important factors in the creation of gender inequality, the “ideological forces that drive these effects and exacerbate the subjugation of women” require scrutiny.

“I’m Not Voting for Her: Polling Discrepancies and Female Candidates”

Stout, Christopher T.; Kline, Reuben. Political Behavior, September 2011, Vol. 33, No. 3. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9137-6.

Findings: Two-thirds, or 66%, of pre-election polls under-predicted how well a female candidate would ultimately fare at the polls, compared to under-predicting only 43.3% of a male candidate’s performance. “When compared to [similar] white male candidates … female candidates performed significantly better in the final results than would be predicted by pre-election polls to the tune of about three and a half percentage points.” The age and gender of voters and the social context of the state accounted for approximately 25% of the gap between pre-election polling predictions and election outcomes. The more women working in a given state, the lower the chances are that pre-election polls will underestimate the support for a female candidate. In fact, pre-election polls for female candidates in states with a robust female labor force tended to overestimate public support by a small percentage.

“Gender Differences in the Salaries of Physician Researchers”

Jagsi, Reshma; Griffith, Kent A.; Stewart, Abigail; Sambuco, Dana; DeCastro, Rochelle; Ubel, Peter A. Journal of the American Medical Association, June 2012, Vol. 307, No. 22.

Results: “The mean salary within our cohort was $167,669 (95% CI, $158,417-$176,922) for women and $200,433 (95% CI, $194,249-$206,617) for men. Male gender was associated with higher salary (+$13,399; P=.001) even after adjustment in the final model for specialty, academic rank, leadership positions, publications, and research time. [Analysis] indicated that the expected mean salary for women, if they retained their other measured characteristics but their gender was male, would be $12,194 higher than observed…. Gender differences in salary exist in this select, homogeneous cohort of mid-career academic physicians, even after adjustment for differences in specialty, institutional characteristics, academic productivity, academic rank, work hours, and other factors.”

“Job Strain, Job Insecurity and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the Women’s Health Study”

Slopen, N.; Glynn, R.J.; Buring, J.E.; Lewis, T.T.; Williams, D.R.; et al. PLoS One, Vol. 7, No. 7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040512.

Abstract: “We examine the relationship between job strain, job insecurity and incident [cardiovascular disease] over 10 years of follow-up among 22,086 participants in the Women’s Health Study…. High strain and active jobs, but not job insecurity, were related to increased CVD risk among women. Both job strain and job insecurity were significantly related to CVD risk factors. With the increase of women in the workforce, these data emphasize the importance of addressing job strain in CVD prevention efforts among working women.”

Tags: research roundup, women and work