Competition from China appears to be hobbling innovation in the United States, say the authors of a new study that juxtaposes import penetration and patent applications.

The issue: A company’s innovation is sometimes measured by the number of its patent applications. Patents, the idea goes, indicate spending on research and development, which is especially key in the manufacturing sector. What does it mean when patent applications fall?

China’s role as a manufacturing behemoth has upset traditional economic relationships around the world. This is especially true in the U.S., which has seen imports from China rise steadily in recent decades. In 1991, China sold $1.6 billion worth of goods in America, according to U.S. government data. In 2014, that figure was $39 billion.

Over the same period, and especially since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, America’s trade deficit with China has swelled.

Economists debate the effects of such import penetration on innovation. Some research shows that import competition leads to greater productivity by encouraging domestic firms to focus efforts on research and development (R&D). But a new paper shows the opposite effect.

An academic study worth reading: “Foreign Competition and Domestic Innovation: Evidence from U.S. Patents,” published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in December 2016.

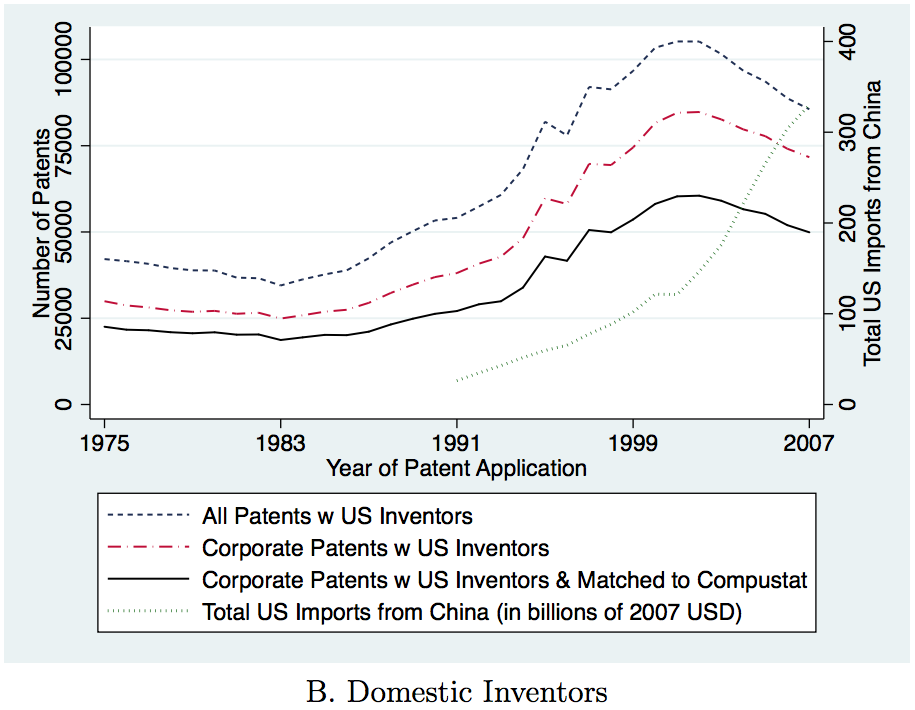

Study summary: MIT economist David Autor and his colleagues look for a relationship between the number of new U.S. patents and Chinese import penetration. They start by examining thousands of American manufacturing firms’ patent applications dating back to 1975, “well before China’s rise as an exporter of manufactured goods.”

They see a rise in the number of patents filed between 1983 and 1999 and then a gradual decline. To explain this drop, they consider and then control for a number of factors, including technological change, economic downturns, firms’ behavior (for example, not disclosing patents so as not to reveal intellectual property) and increasing demands from patent-issuing offices. They also control for industry and firm characteristics associated with different business cycles.

They start by looking only at publicly listed firms but expand to control for private firms as well.

Findings:

- American industries, such as manufacturing, that have seen greater import penetration from China “have suffered larger reductions in patenting.” Consequently, the greater the import competition from China, the larger the affected firm’s decline in patent growth.

- “Greater import competition causes U.S. firms to contract along every margin of activity that we observe, including sales, employment, capital, and R&D spending.”

- It does not appear that firms change their specialization in response to foreign competition. That is, in response to Chinese competition, “innovating their way out” is not in firms’ survival strategy.

- A 1 percent increase in import penetration from China is associated with a 1.53 percent to 1.65 percent decline in new patent applications.

- The Chinese trade shock is associated with lower profitability for American manufacturers and downsizing in multiple areas, including innovation.

- Import competition appears to hurt innovation more at firms that are less productive, require less capital investment and are less profitable.

- Having a foreign parent company, or being publicly listed, makes no discernible difference in exposure to this form of Chinese competition.

Helpful resources:

The U.S. Census Bureau publishes monthly trade data, including detailed breakdowns for major partners like China. So does the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database.

The National Science Foundation’s Business R&D and Innovation Survey includes key data on some 1.5 million for-profit companies.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office explains the registration process and hosts a database of patents dating back to 1790.

Other research:

Our 2016 research roundup on free trade discusses how reduced international trade barriers can help as well as hurt American jobs. Free trade may also contribute to political and ethnic polarization in the U.S.

This 2016 study from the Review of Economic Studies looks at import competition and patent applications in Europe. It found Chinese competition may have led to increased patent applications and high-tech investment, but also increased unemployment among unskilled workers.

This blog from the St. Louis Federal Reserve explains some ways in which U.S. foreign trade has changed in recent decades.

Keywords: Free trade, competition, innovation, patents, China, American workers