Usage of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — more generically referred to as “food stamps” — has risen to record levels in recent years. Nearly 48 million Americans, or 23 million households, use the program, according to 2013 USDA data. The average SNAP recipient sees a monthly benefit of $133 — a figure that has remained roughly unchanged over the past few years. More than two-thirds of beneficiaries are children, the elderly or disabled persons. In general, a household of three is eligible in 2013 only if its net monthly income is below $1,591 a month — roughly $19,100 a year.

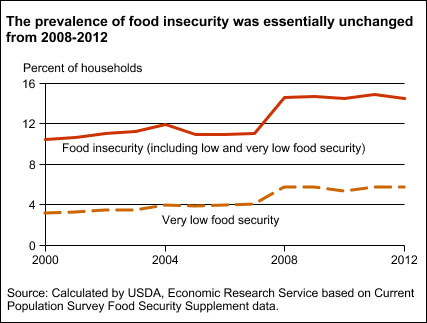

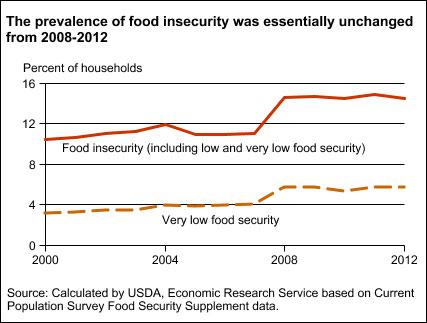

The percentage of eligible persons using the program has risen dramatically over the past decade, from 54% in 2001 to 87% in 2011, according to Peter Ganong and Jeffrey Liebman of Harvard. They found in a 2013 study that higher local unemployment and the Great Recession economy explain about two-thirds of this increased demand, while looser rules and lower eligibility requirements explain about 18% of the increase. This issue of rule changes — and the expanding costs of SNAP because of wider participation — has been a hot political issue in Congress. The House has voted to significantly trim the program, even as food insecurity has remained at elevated levels post-Recession.

Despite these social programs, about 14.5% of all Americans continue to face issues of food insecurity — the inability to provide enough food during certain times in the year. Benefits under SNAP have been incrementally increased over time to account for rising costs, but no provision is made for the geographical variation in costs of food across America. Usage of the program varies by Congressional district (the USDA provides a detailed statistical breakdown of each area). Although extensive research has focused on food insecurity in the developing world, little prior research has looked at the potential effects of food cost variations on low-income U.S. families and identified the precise statistical relationship.

A 2013 study published in Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, “Do High Food Prices Increase Food Insecurity in the United States?” examines Census and USDA data to build a local food price index and analyze the average experience of SNAP households. The researchers, Christian A. Gregory and Alisha Coleman-Jensen of USDA Economic Research Service, note that to date “there has been no direct examination of the relationship between food prices and food insecurity for households in the United States.”

The study’s findings include:

- Overall, local food prices “significantly” affect food insecurity for those households at 200% or less of the poverty line: “Those in the highest-priced areas are significantly more likely to be food insecure: Households in high-priced areas are 8.6, 8.3, and 10.0 percentage points more likely to experience household, adult and child food insecurity, respectively, compared to those in low-priced areas.”

- The data suggest that “SNAP has large and significant effects on the probability of food insecurity for participants: SNAP reduces the probability of household, adult, and child food insecurity by 17.4, 11.2 and 20.6 percentage points, which amount to reductions of 33.7%, 24.6% and 70.3% of prevalence for these populations.”

- In addition, “SNAP households that live in the places with the highest quartile of food prices are between 8 and 10 percentage points (between 15% and 20%) more likely to be food insecure than those in the lowest quartile of food prices.”

“Our results indicate that SNAP could do better to ameliorate food insecurity and its effects by indexing benefits to local prices,” the researchers write. “Although we think that these effects are important, we are also aware that the question about how to index SNAP benefits is both technically difficult and politically sensitive.”

Related research: A 2013 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “The Effect of the Safety Net Programs on Food Insecurity,” looks more broadly at the range of government programs assisting families. The study examines outcomes for families with low food security that have income 300% or more below the poverty line. The authors, Lucie Schmidt, Lara Shore-Sheppard and Tara Watson of Williams College, find “evidence that a generous cash and food safety net does reduce low food security in families with children…. Our findings suggest that each $1000 in cash or food benefits for which families are eligible reduces low food security by 2 percentage points, and that each $1000 actually received reduces low food security by 4 percentage points.”

Keywords: poverty