Few mayors run for higher office. And female mayors are much less likely to view positions such as governor and U.S. senator as appealing.

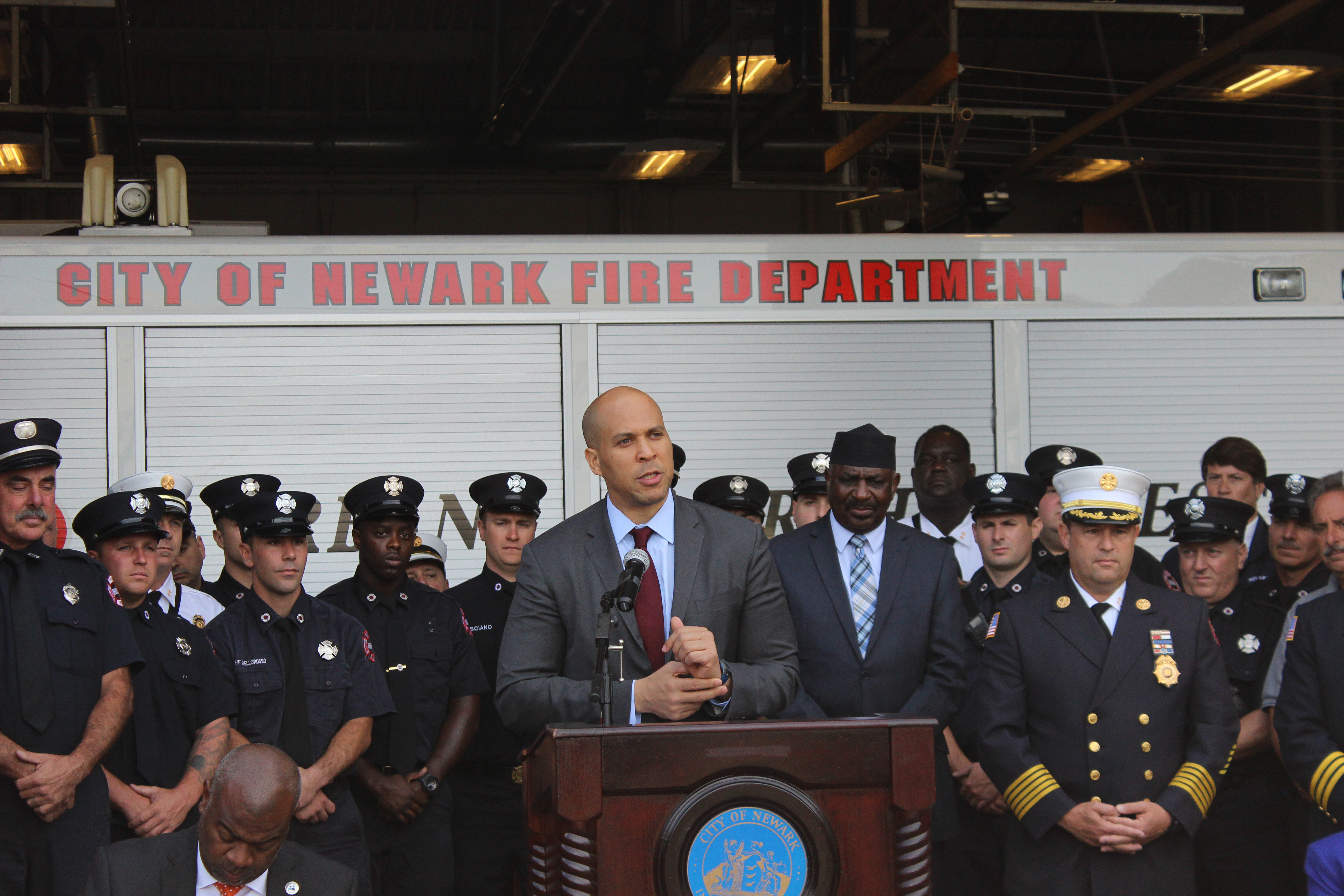

The issue: A number of high-profile leaders began their political careers as mayors. U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, who sought the Democratic nomination for president in 2016, started out as the mayor of Burlington, Vermont. U.S. Sen. Cory Booker was the mayor of Newark for more than seven years. Before becoming the governor of Tennessee, Bill Haslam served as mayor of Knoxville from 2003 to 2011.

Do mayoral posts live up to their reputations as a fast track to a political career? New research looks at the career paths of mayors of large cities and the characteristics of those who aspire to offices at the state or national level.

A study worth checking out: “Do Mayors Run for Higher Office? New Evidence on Progressive Ambition,” published in American Politics Research, 2018.

More about this study: A research team led by Katherine Levine Einstein of Boston University examined the career trajectories of every mayor who led a major city between 1992 and 2015. The researchers also collected data on the cities’ demographics from U.S. censuses in 1990, 2000 and 2010. To better understand mayors’ views on higher office, Einstein and her colleagues analyzed responses from a national survey of more than 90 mayors in cities with more than 75,000 people.

Key takeaways:

- About 15 percent of mayors ran for a higher office. About 5 percent won election to a higher office.

- Of those who ran for higher office, 34 percent sought legislative seats and 41 percent ran for governor.

- Mayors generally expressed a lack of enthusiasm for higher office, reporting that if they could not be the mayor of their cities, they would be attracted to nongovernmental work. More than 80 percent of mayors rated this type of work as “very appealing” or “appealing.” A majority did indicate the following government jobs were very or somewhat appealing: governor, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary, U.S. Transportation Secretary, U.S. senator.

- Black mayors appear to be less likely than those of other races and ethnicities to run for higher office.

- Female mayors were 20 to 30 percentage points less likely than male mayors to view higher offices as appealing. However, 75 percent of both male and female mayors said they had been recruited for a higher office.

- “The seemingly widespread perceptions of governing inefficacy at the state and (especially) federal levels have led mayors to view cities as the only places where exciting legislation can get passed. As the mayor of a western city put it, cities ‘are where you actually get work done.’”

Helpful resources:

- The United States Conference of Mayors is an association of mayors from cities with populations of 30,000 or more. Similarly, the National League of Cities is an advocacy organization representing U.S. cities and their leaders.

- Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute of Politics and Center for American Women and Politics offer fact sheets and research reports on various levels of elected office.

- The National Conference of State Legislators has compiled a chart detailing the qualifications needed to become a legislator in each state.

Related research:

- A 2014 report from Boston University, “Mayoral Policy Making: Results from the 21st-Century Mayor’s Leadership Survey,” examines the perspectives of mayors on a range of issues and finds their core priorities are similar.

- A 2014 study published in the Journal of Public Economics, “Does Gender Matter for Political Leadership? The Case of U.S. Mayors,” suggests that a mayor’s gender does not seem to affect policy decisions in U.S. cities.

- A 2013 study in the American Political Science Review, “No Strength in Numbers: The Failure of Big-City Bills in American State Legislatures, 1880–2000,” considers five possible explanations for cities’ relative lack of political power.