A new online course from First Draft helps journalists use free tools to track down, source and verify information they find online.

A video appears to show regime planes bombing civilians in Syria; someone who looks much like a beloved professor appears holding a torch at a neo-Nazi rally. If credible, these are leads. But how do we know if they are credible?

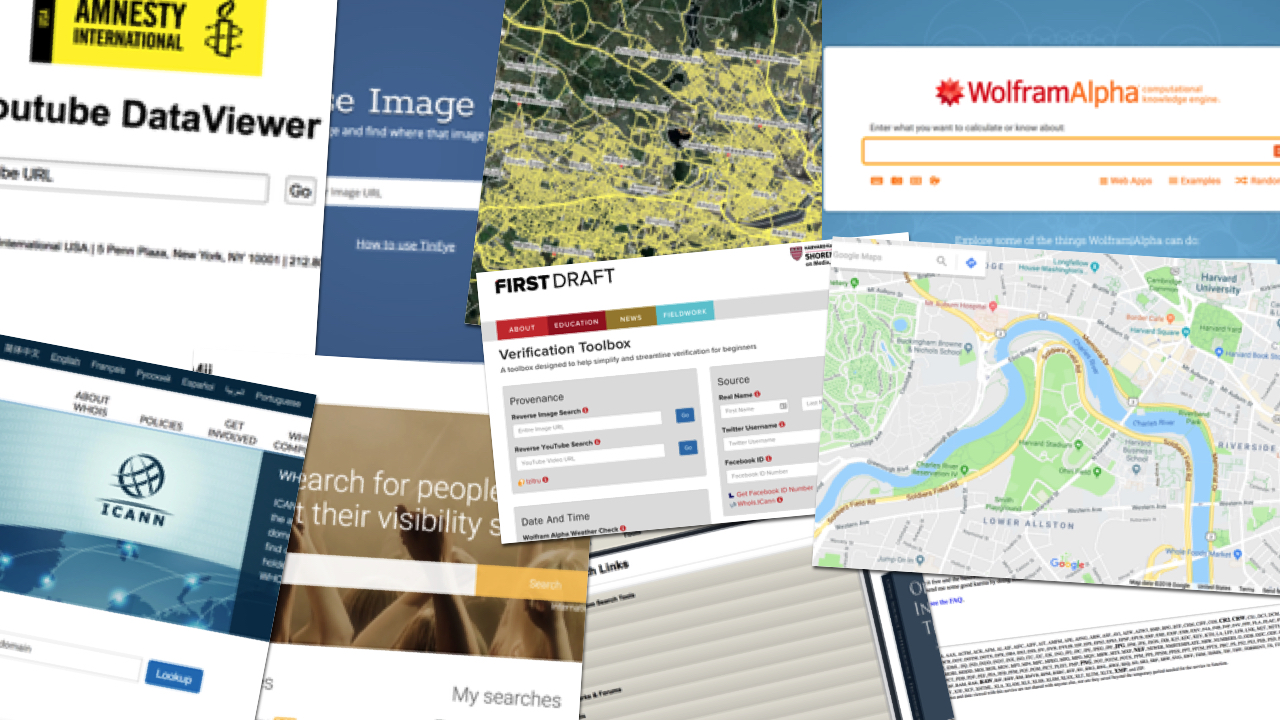

A new online course from First Draft introduces cutting-edge tools for verifying imagery and claims made online, especially by social media accounts. First Draft — our partner across the hall at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center — is leading the development of curricula to help journalists navigate the thorny world of social media.

First Draft’s course, which is free, is built around a number of internet plugins and tools that anyone can use to trace a video or photo’s provenance, test for manipulation, trace someone’s online footprint, or verify the date in an image file’s metadata. But it is much more than a list of tools: Clare Wardle and her team demonstrate how to use each, with examples.

Here are five takeaways from the course (in no special order):

1: Viral videos: Be skeptical

When suicide bombers attacked the Brussels airport in 2016, a video quickly circulated online purporting to show the aftermath. Journalists jumped on it and credited the woman who tweeted it. But she had simply posted the video to Twitter, she later wrote; someone else had shot it. Indeed, as this example shows, imagery may first appear on closed messaging applications, like WhatsApp or Telegram, and only later emerge on Facebook or YouTube. In other cases, you can find many scrapes (versions) of the same video on YouTube. How do you know which is original or where it really came from? Be skeptical, First Draft warns: “The problem is that you don’t have the name of the person who originally captured the content; you often also don’t have the right date.”

2: Provenance

What if we’re not sure a video is authentic? Taking the example of an alleged chemical weapons attack in Syria in April 2017, First Draft uses a number of tools to determine that a YouTube video is likely what it appears to be: They use Google Translate to read the Arabic titles, Amnesty’s YouTube DataViewer to determine if the video was uploaded around the time when it was allegedly shot, and other free online tools.

3: Digital footprints: Trace someone online

Dylann Roof opened fire in Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015. After police announced he was a suspect, journalists helped with the search.

The First Draft course demonstrates tools to trace people and corroborate their whereabouts, starting with a database known as inteltechniques.com. There, you can search by someone’s real name, a social media username, an email address, Twitter handle, someone’s unique Facebook user number and more.

4: Verify a photo or video by checking the weather, Google Street View, and searching social networks for keywords

A photo appears to show lightning striking a tree. Verify that the date and the weather match with Wolfram Alpha’s database. In another case study, First Draft identifies the location of a bombed building in Yemen.

5: Geolocation — “matching clues in your pictures and videos with satellite imagery and other pictures of the terrain”

Location manipulation is easy. Anyone can change a photo’s metadata (and social media platforms like Facebook automatically strip it out). But with the right tools and online mapping software, you can often track down where a photo was shot. This is more than Google Maps: In other countries, other mapping tools dominate. Check out First Draft’s list.

This course offers much more. We’d recommend it for any journalist (and anyone) seeking a healthier relationship with social media.

You can sign up for the course by going to firstdraftnews.org/learn and clicking the “Get Free Access” button. Faculty can integrate parts of the course into their own lesson plans.