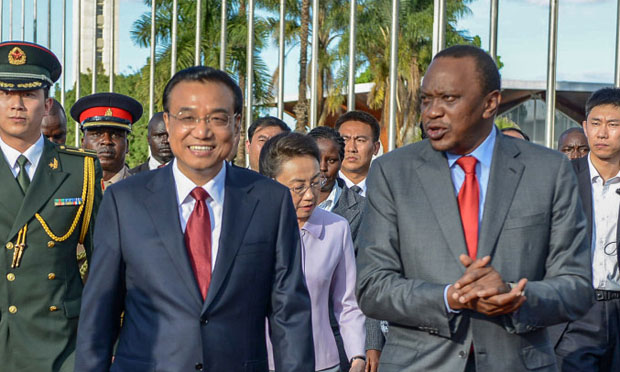

In May 2014 Chinese premier Li Keqiang stood next to Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta in Nairobi. The Chinese leader, on a tour of several African countries, pledged the equivalent of nearly $4 billion to fund the first stage of a railway project linking Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and South Sudan. The project was one of the largest yet by Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and Mr. Li said that they and other Chinese firms would play an integral part in the railway’s development. The project, he said, is also an illustration of “equal co-operation and mutual benefit” between China and Africa.

Over the past few decades, state-backed Chinese companies have built airports, highways and power stations across Africa in growing numbers. They’ve also received their share of criticism: A 2014 article in the New York Times indicated that far from being win-win, “these projects have also left many countries saddled with heavy debts and other problems, from environmental conflict to labor strife.” In a 2013 opinion piece in the Financial Times, Nigeria’s then-Central Bank governor Lamido Sanusi equated Chinese companies’ actions across Africa to colonialism. And in a 2012 speech in Senegal, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton asserted that the United States, unlike China, offers “a model of sustainable partnership that adds value, rather than extracts it.”

A 2014 study in the Journal of Contemporary China, “Chinese State-owned Enterprises in Africa: Ambassadors or Freebooters?” examines the perceptions of Chinese state-backed companies in Africa and the actual nature of their investments and behavior. The researcher, Xu Yi-Chong of the Center for Governance and Public Policy at Griffith University in Australia, notes that academic findings on China’s role in Africa are not always consistent with popular perceptions:

SOEs are seen to be the agents in spreading ‘bad behaviour’ from China to Africa, whether corruption, human and/or labour rights violations, environmental pollution and even crimes, and more importantly, spreading to African countries the practices of ‘state capitalism.’ The role of Chinese SOEs in Africa is puzzling [however]. If, as some claim, SOEs are the agents of the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), pursuing the strategic goals set by the CCP, either by getting control of natural resources, inserting its power and influence, or undermining the values and practices of Western democracies, why and how are some of their activities undermining these objectives, as argued by some other scholars?

In the study, Yi-Chong seeks to understand which state-owned and private Chinese firms are present in Africa, their characteristics and activities, and their relationship with the government. The study’s findings include:

- Large central state-owned enterprises are small in number but account for 77% of China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa.

- Chinese foreign direct investment to Africa increased from $7.5 million in 2003 to $2.1 billion in 2010, yet Africa accounted for only 3% of China’s total foreign direct investment in 2010 and 13.8% in the period 2005–2010.

- Africa increasingly is seen as a large market where Chinese SOEs and private firms compete for business. Revenues of construction companies in central and southern Africa grew by 31.7% to $27.5 billion in 2009. The share of Chinese enterprises in the African market rose from 26.9% in 2007 to 42.4% in 2008, then fell to 36.6% in 2009.

- There is a great deal of diversity in the Chinese SOEs present in Africa: Some dominate their sectors, while others have to compete with other SOEs. “While these large SOEs pioneered China’s involvement in Africa, their activities have brought to Africa a range of smaller and diverse SOEs and private players.”

- The small SOEs and private enterprises that accompany the large SOEs are often poorly regulated. These firms “have brought into Africa fierce and unregulated competition and practices which are not acceptable in Western democracies and African countries. Tension therefore often arises between local people and these poorly regulated small enterprises.”

- While state-owned enterprises in China are encouraged and supported by the state to “go global,” the government has limited capacity to control and regulate the smaller Chinese companies doing business across the continent.

Yi-Chong concludes that it’s overly simplistic to say China’s state-owned enterprises are operating in Africa solely as an extension of government policy “interested in looting the land.” The companies are in Africa because they see a business opportunity and the Chinese government doesn’t have the capacity to regulate the small companies that accompany them. “This is not an excuse for the ‘bad’ behavior of Chinese firms in Africa,” the author writes, “but it does explain why increasingly Chinese involvement and activities in Africa are contradictory or even undermining the objectives of the central government.”

Related research: In a 2014 RAND Corporation report, “Chinese Engagement in Africa: Drivers, Reactions, and Implications for U.S. Policy,” Larry Hanauer and Lyle Morris analyzes China-Africa relations as a “vibrant, two-way dynamic in which both sides adjust to policy initiatives and popular perceptions emanating from the other.” In a 2008 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “China’s Growing Economic Activity in Africa,” Hany Besada, Yang Wang and John Whalley find that “China’s growing presence in Africa … largely reflects commercial rather than other political considerations.”

Keywords: China, Africa, state-owned enterprises, resource extraction, Asia