Political polarization is often thought of as a relatively recent phenomenon in the United States — the Tea Party came to prominence in the late-2000s, after all — but research has shown that it has much deeper roots. A 2006 study in the Journal of Politics found that ideological divisions had been on the rise since the 1970s: “These divisions are not confined to a small minority of activists — they involve a large segment of the public and the deepest divisions are found among the most interested, informed and active citizens.”

A Princeton University study published the same year found a connection between polarization and inequality: The higher a state’s level of income inequality, the more partisan its congressional voting patterns were — Republicans shifted farther right, while Democrats moved to the left. A 2012 Pew Research study showed that the pattern had continued, with political polarization rising significantly during the second term of President George W. Bush and continuing through President Obama’s two terms. A substantial body of research has also shown that polarization isn’t restricted to politics, and can influence everything from where people live to whom they date.

A June 2014 report by the Pew Research Center, “Political Polarization in the American Public,” uses data from a national survey of 10,013 adults to explore how political polarization affects government, society and people’s personal lives. Its key findings include:

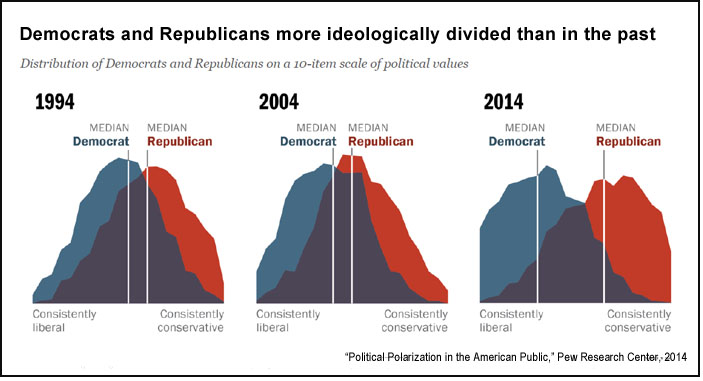

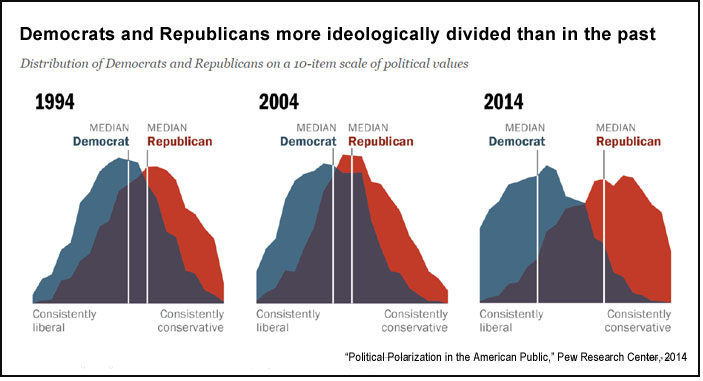

- Americans have become more consistent in their ideological beliefs. “The overall share of Americans who express consistently conservative or consistently liberal opinions has doubled over the past two decades from 10% to 21%.”

- Ideological views today are “much more closely aligned with partisanship than in the past.” This becomes apparent when tracking 10 political values questions asked since 1994: “More Democrats now give uniformly liberal responses, and more Republicans give uniformly conservative responses than at any point in the last 20 years.”

- Economic issues and the role of government have become points of substantial consolidation both in the Republican and the Democratic camp. “37% of Republicans are consistently conservative and 36% of Democrats are consistently liberal on a five-item subset of the scale restricted to just the items about economic policy and the size of government. In 1994, those proportions were 23% and 21%, respectively.”

- In addition, “the level of antipathy that members of each party feel toward the opposing party has surged over the past two decades. Not only do greater numbers of those in both parties have negative views of the other side, those negative views are increasingly intense. And today, many go so far as to say that the opposing party’s policies threaten the nation’s well-being. 36% of Republicans and Republican leaners say that Democratic policies threaten the nation, while 27% of Democrats and Democratic leaners view GOP policies in equally stark terms”

- Antipathy for the opposite party is correlated with political participation. “Republicans who hold a very unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party are 18 points more likely than those whose opinion is mostly unfavorable to say they always vote. They are also almost twice as likely to have made a donation to a campaign or candidate (23% vs. 12%). Importantly, how Republicans view their own political party has little association with their participation in these ways. Those who hold very favorable views of the GOP are no more or less likely to be politically active than those with less favorable views.”

- The study finds that on different measures “those who hold consistently liberal or conservative views, and who hold strongly negative views of the other political party, are far more likely to participate in the political process than the rest of the nation.” Even after controlling for confounding variables like age, education, income and other demographic factors, “the relationship between ideological consistency and engagement persists.”

- In addition, conservatives and liberals increasingly find themselves in social environments which act as ideological silos. “Just 35% of Americans say “most of my close friends share my views on government and politics,” while about as many (39%) say “some of my friends share my views, but many do not.” In comparison, “among consistent conservatives, roughly twice as many say most of their close friends share their views as say many of their friends do not (63% vs. 30%).

The authors conclude that “because political participation and activism are so much higher among the more ideologically polarized elements of the population, these voices are over-represented in the political process.” Nevertheless they remain a minority of voters, donors or campaign activists. “While the left and the right may speak louder in the political process, they do not necessarily drown out other elements of the public entirely. And this may be one reason why, even in lower-turnout primaries, the more ideological candidates do not always carry the day.”

Keywords: polarization, political parties, Congress, society, presidency